DAYTON, Ohio — The transportation engineers who designed Dayton’s streets and neighborhoods decades ago weren’t thinking about a world in which people bicycled, walked or ran to get around town. And they certainly never envisioned e-scooters would be a thing.

What You Need To Know

- The City of Dayton will spend the next year developing an Active Transportation Plan

- Active transportation is traditionally known as any human-powered mode of transportation, but for these purposes, it can also include things like e-scooters

- As part of the process, the city asked residents to fill out a survey to provide information about how they get around town and if there are any improvements they’d like to see made

- The community engagement process runs through July; the city plans to assemble the finalize the plan next year

But today that’s the reality in the Gem City and many cities across the United States.

As an initial step toward modernizing its infrastructure, the City of Dayton will spend the next year developing what’s called an Active Transportation Plan. And the city is asking residents to take a lead role in creating it.

Active transportation is a phrase used to describe any human-powered mode of getting around, whether a person uses it for recreation or to commute. That includes walking, running and bicycling as well as things such as skateboarding and rollerblading.

The overall goal of the plan is to use the residents’ suggestions to make Dayton more accessible to anyone trying to enjoy the city without the use of a car.

As part of the plan, the city wants feedback from residents, businesses and frequent visitors to come up with recommendations for improving Dayton’s existing biking and running networks.

“There’s a really strong recognition in our city that our cycling and walking networks are part of a new wave of how people choose to get around,” said Susan Vincent, a planner in Dayton’s Department of Planning.

Vincent’s work focuses on neighborhoods and development. She’s helping to run the summer-long engagement component of the transportation plan.

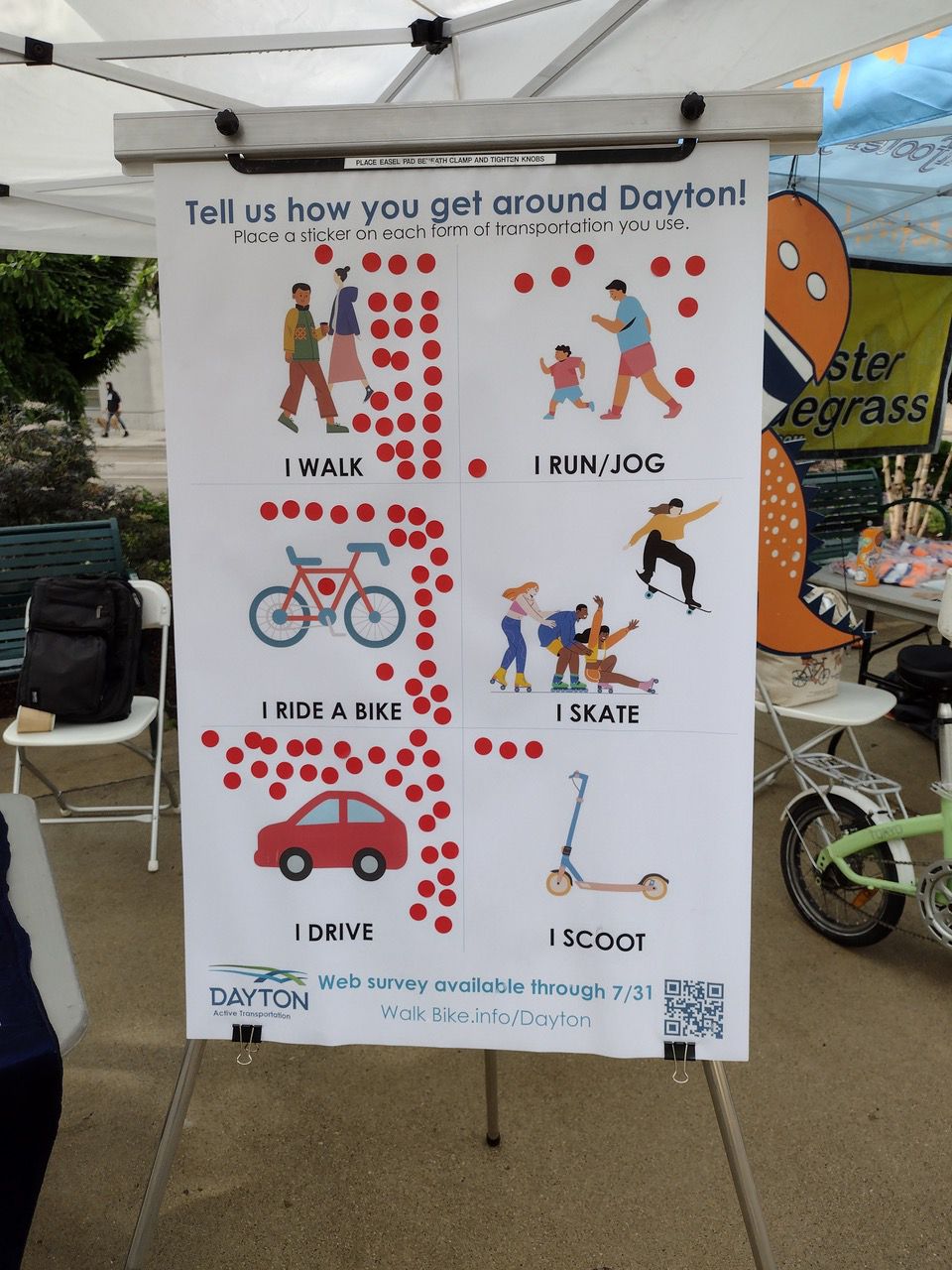

One way the city is accepting feedback is through an online survey. It asks people how they get around Dayton (bike, walking, etc.), how often they use those modes of transportation and why they choose to use them.

The city also wants to know if there are any obstacles to traveling within the city. The survey lets a person provide specific feedback and suggestions for improvement.

There’s also an interactive online map for location-specific suggestions. The city plans to host outreach events as well.

The survey and the overall engagement period will remain open through July 31.

The best way to improve something that doesn’t work? Ask those who use it most

Dayton’s transportation engineers have a “pretty good understanding of how people use city infrastructure,” Vincent said, but they haven’t ever asked the community to discuss “why” they use it the way they do.

That’s why the community engagement component of the Active Transportation Plan is so important, Vincent said. The city will develop a “comprehensive and thorough” playbook focused on the needs and priorities of residents.

“They’re the ones actually using our infrastructure, so it only makes sense that they play a role in helping to prioritize the projects,” Vincent added.

There are few people as excited or invested in the plan's outcome as Ryan Vingris. A competitive cyclist, Vingris loves that the city is coming to residents like himself to become “actively involved” in the decision-making process.

“It’s them coming to us rather than me having to reach out to them to express my opinion, which makes it a lot easier to get my point of view across to the city,” he added. “It’s just excellent.”

The survey took about 10 minutes, Vingris said, and that’s with him leaving “a bunch of comments from things I’d like to see” in the city.

‘I don’t feel safe’

Vingris has spent more than half of his life cycling the roadways of greater Dayton.

The 40-year-old and his wife, Dana, also a competitive cyclist, moved to downtown’s Huffman Historic District about four years ago in part because of how “walkable and rideable” the neighborhood has become.

The couple uses the city’s current bike system to get around town for heading to the grocery store to make it to a favorite local hangout.

It provides great access for recreational riding, too. From RiverScape MetroPark, they can hit about 300 miles of paved, well-maintained bike path.

“Our bike racing friends in Columbus and Cleveland (Ohio), they actually have to drive to get to a bike path in order to train. I can walk out my front door and within 2 miles, I’m able to ride as long as I want to.”

The city has made a lot of progress in recent years, Vingris said, but he feels additional investments will go a long way toward improving safety for cyclists and pedestrians.

Vingris and his wife have had a few friends get hit and killed by drivers over the years.

“Once you get out of the city, or even certain parts of the city, it feels a little unsafe,” he said.

A lack of bike-specific infrastructure, protected bike lanes for example, make it “feel like cars are the priority,” said Vingris. Marked lanes are nice, he said, but they don’t offer any protection to riders.

“I’d definitely feel more safe with physical barriers as opposed to just paint on the road,” he added.

While the couple hopes their children — they have an almost-2-year-old and another on the way — develop a passion for bikes as they get older, they aren’t sure they want to go into road cycling out of fear they could get hurt.

They recently had a “difficult discussion” about how they plan to raise their kids in bike culture if things don’t improve.

“We definitely want them to be interested in cycling,” Vingris said, “but we want it to be done safely. We hope that as the city makes these improvements with regard to physical safety, they’ll be able to enjoy that as well.”

His kids’ future is a major part of the reason Vingris is so excited about the Active Transportation Plan. And City Commissioner Darryl Fairchild agrees.

Fairchild suffered serious injuries in a bike accident several years ago that left him paralyzed from the waist down. He remains an avid hand-cyclist today, and he’s excited by the prospect of making the city both safer and more accessible.

Through the plan, Dayton officials will look for ways to improve access to the city for those who rely on the use of strollers, wheelchairs and other mobility devices.

“It’s important to hear from residents from all walks of life and various backgrounds,” Fairchild said, “to ensure the system design works for as many people as possible.”

“I value this input because the conversations advance our desire to be a welcoming and inclusive city,” he added. “Ultimately, this engagement leads to the important goal which is to enhance our transportation infrastructure and create a more accessible, healthier and sustainable city.”

How did we get here? Clue: It wasn’t by bike

The decision to develop the plan was “fairly organic,” Vincent said. It grew out of a recognition that the existing Bike Action Plan needed to be updated to accommodate contemporary needs.

There are more runners, e-scooters, bike-share options, rollerbladers and, in general, people using alternative modes of transportation than ever before, Vincent said.

Some use those things for recreation, while others rely on those methods to get from point A to point B.

Dayton plans to combine the Active Transportation Plan with its Safe Routes to Schools Travel Plan, which expires in 2022-23.

“By adding a chapter on ‘how youth move,’ we will be able to combine both documents into one plan,” Vincent said. It will ensure the document includes the “voices of young people” — from elementary school age to those younger than 21 — in the planning process.

The plan will identify recommendations for Dayton to make to its bicycle and pedestrian networks. It’ll include a prioritized project list, which is an essential component for securing infrastructure funding.

Dayton officials hope to take advantage of the unprecedented levels of federal money soon to become available to communities across the country as part of the $1 trillion Bipartisan Infrastructure Law.

The overall goal is to create solutions that improve safety across and accessibility across the city. A focal point is equity.

“As climate change starts to get more serious, as different health issues become more serious, we all are trying to figure out how to make our communities healthier and make it easier for people to get from one place to another without a car,” she added.

It’s also a chance to ask to see if any changes might increase their usage or change the way they use it.

For instance, instead of solely riding a bike path for exercise, a change like protected bike lanes may inspire a person to use their bike to get from place to place.

The current design of the city’s primary traffic corridors aimed to move people through them as quickly as possible, Vincent said. That was the traffic engineering practice in the 1960s and ‘70s when the city built a lot of its current streets.

And it’s not just downtown, though. It’s also about updating the surrounding neighborhoods as well.

“We are really trying to right-size our streets to the number of people who live here and to an understanding that streets aren’t just for cars, they’re for everybody,” Vincent said. “Making sure they’re safe enough and the speeds are at a level they’re going to make our cyclists and pedestrians safer, as well.”

Dayton has a “liveable streets policy” focused on “building front to building front” to make sure the entire roadway, including the sidewalk, is welcoming and “feels lively,” Vincent said.

The plan itself will provide a comprehensive, prioritized infrastructure project list guided by the community input.

The recommendations will include ideas for new programs as well. An in-progress example is the mountain bike park in the Carillon neighborhood.

The pilot will give free mountain bikes and training to kids Carillon and neighboring Edgemont. Many of them don’t have access to bikes.

Since opening the survey, the City of Dayton has received nearly 300 responses, Vincent said. They’re looking to collect more over the next few weeks.

“We’ve had a great start and we appreciate everyone’s feedback so far,” Vincent said. “We want to see as many people comment as possible, though. The more comments we receive, the more feedback we have to make meaningful changes to our city.”