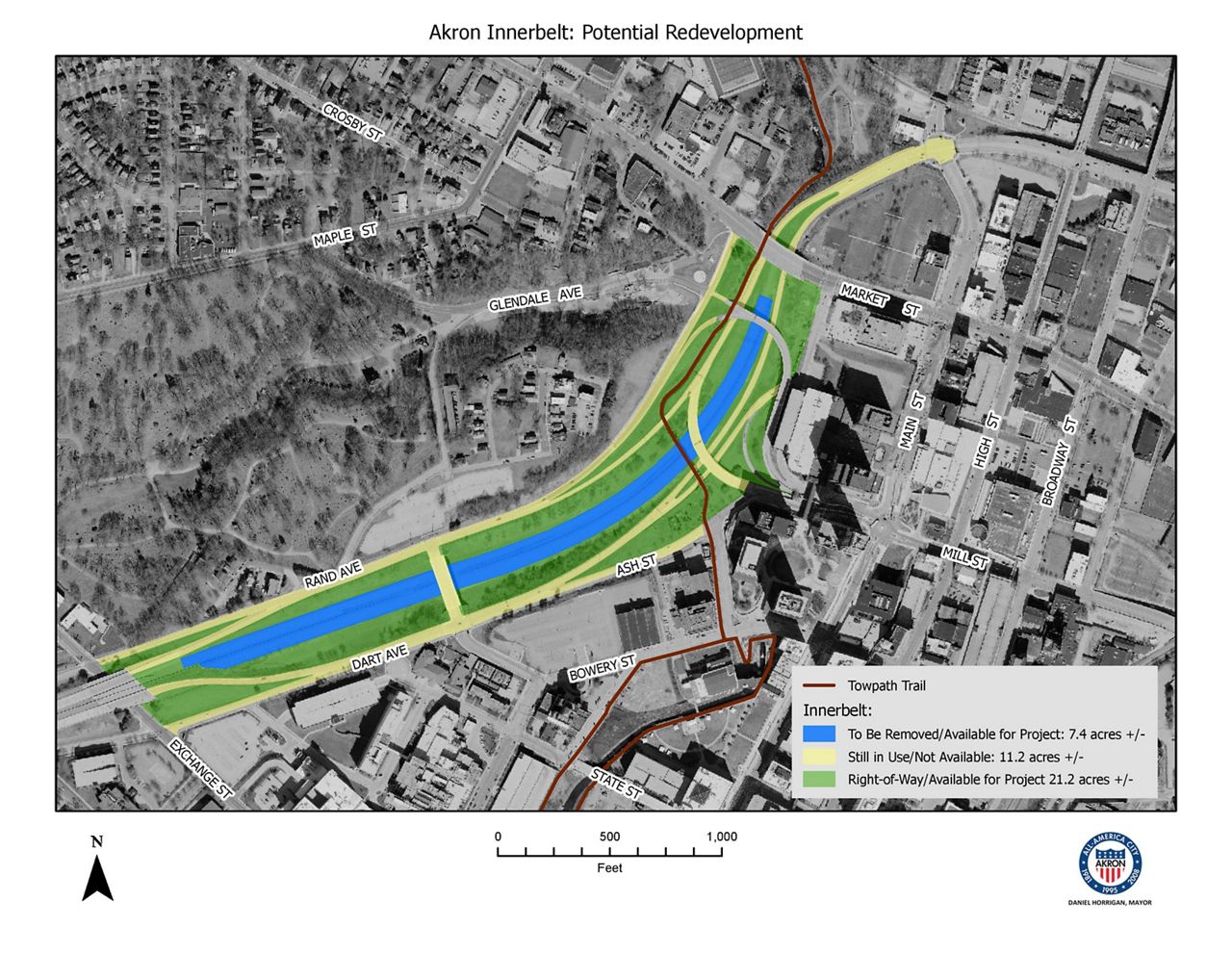

AKRON, Ohio — The future of about 33 acres of the Innerbelt Highway in downtown Akron is expected to be decided by residents in new process the city said will take years to produce permanent results.

Reconnecting Our Community asks residents to weigh in on what they would like to see built on that section of the Innerbelt, also known as Route 59.

Public engagement sessions will be held over the next year and a new website will warehouse information as the process moves ahead, the city said. Residents can sign up on a mailing list to keep current on the progress or share their story digitally for a history archive the city plans to create.

To lead the project, the city enlisted urban designer Liz Ogbu of Studio O. Ogbu, who has worked around the globe on various projects requiring community-centric solutions, has been working for the past year or so with an Innerbelt advisory group.

The group comprises representatives from city council, the business community and local nonprofits, as well as those whose families or businesses were displaced.

Built as a six-lane road stretching from downtown to I-77, the Innerbelt Highway was intended to alleviate congestion and bring vibrancy back to downtown Akron, historic records show.

When Akron planners issued a report touting the Innerbelt highway in 1963, the number of vehicles on Akron freeways had grown to nearly four times what was projected in 1947. Planners attributed it to the “rapid increase in motor vehicle registration and the rapid decline of rider use of mass transit facilities.”

The Innerbelt was designed to accommodate commuters coming from Cuyahoga Falls, Kent and Barberton, providing easy access to Akron’s central business district, which in turn was expected to expedite expansion, the report said.

To accommodate those three hubs, the Innerbelt was designed to cut off the north end of Main Street, as well as the West Hill and Summit Lake neighborhoods, bisecting the city’s largest Black business district and neighborhood, cutting them off from downtown.

But the Innerbelt never met planners’ expectations. Designed to carry 100,000 vehicles per day, it has never averaged more than about 20,000, the city said.

As early as 1977, it was clear the highway, still till not done, would not succeed.

Frank Kendrick of the University of Akron urban studies department, published a scholarly article in the Ohio Journal of Science, spelling out the woes the Innerbelt Highway would cause. He noted that although the highway had been announced in 1963, by 1977 less than a mile of it was completed.

“This particular freeway, although only partially finished, has had numerous social, economic, environmental effects and if finished will have many more,” Kendrick wrote. “Some of the effects have either tended to perpetuate or aggravate already existing problems, with the result that the overall quality of life has been impacted thereby.”

Over the years, redevelopment of the Innerbelt has taken on a kind of local mystique.

In 2015, urban artist Hunter Franks hosted 500 plates on the Innerbelt Highway, serving 500 Akronites a meal on the closed highway. A couple years later, he built the Innerbelt Forest there, bringing in 90 trees and seating, to help locals imagine the possibilities.

A collaborative design charrette was held in 2017 at Kent State University’s College of Architecture and Environmental Design. Attendees dreamed up a museum in the Howard Street area dedicated to the city's jazz roots, while an open canalway lined with residential and retail offerings was another idea.

One thing most residents seems to agree on is that the plan for the Innerbelt must tie the West Hill and Summit Lake neighborhoods back into the city.

In 2016, the city officially closed the north end of the Innerbelt so crews could remove thousands of tons of concrete to clear the way for redevelopment.

Forward momentum slowed once the pandemic hit, but the Innerbelt committee has been moving ahead behind the scenes, Ogbu said.

The work should be framed through “a lens of repair,” Ogbu said, so dialogue with the Akron families the highway displaced, or their descendants, is important. The conversation has multiple dimensions because the Innerbelt cuts through the heart of the city.

“Because it's such a signature space within Akron, it's a conversation Akron has about itself,” she said. “So that brings up all the feels and I think the thing to support people in and understand is that it’s going to be a complex conversation, with many twists and turns.”

Ogbu likened the process to a famous quote by James Baldwin, that not everything that‘s faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it's faced, she said.

“So I think it's so easy for these processes to often be about the cool new thing that's coming, like ‘what can we do with this cool, abandoned freeway?’” Ogbu said. “But I think it's really important that we work with the complete story.”

But the process won’t be quick, according to the city’s timeline. Following the public engagement process this year, the planning department will develop a plan based on feedback and reach out for contractors to activate those ideas between 2023 and 2025.

Much of whatever happens at the site will be “interim” until about 2030 when permanent changes will be begin to be implemented, the city said.

To sign up for updates, visit the city’s Reconnecting Our Community website.