CINCINNATI — Elizabeth Hardin-Klink first heard of the Contemporary Art Center in 2003 while reading a New York Times article about the building.

The piece coincided with the opening of the newly built space, designed by prominent Iraq-born architect Zaha Hadid. The CAC was her first commissioned project in the United States and helped earn her the Pritzker Architecture Prize, often called the Nobel Prize for architecture.

It also was among the first major museum projects in the U.S. designed by a female architect.

In his review, famed architecture critic Herbert Muschamp labeled the new museum “the most important American building to be completed since the end of the Cold War.”

He cited Hadid’s innovative “urban carpet” design, which sought to dynamically connect the sidewalks of one of Cincinnati’s busiest intersections, Sixth and Walnut streets, with the inside of the building.

At the time, the design of the six-story, 85,000-square-foot museum was seen as visionary – not just for its futuristic and asymmetrical construction, but for how it linked the center of urban life.

Hardin-Klink got her hands on a copy of the newspaper days after the new building opened. Reading the critic’s bold comment, she “dragged” her family on a pilgrimage from Troy, Ohio, to check it out.

“I had to see what all the fuss was about,” said Hardin-Klink, a sculptor and art educator. “We’re talking about one of the most impactful buildings of our generation.”

That “fuss” came from the creativity of the late Hadid, who brought her futuristic sketches to life in some of the world’s greatest cities. Her works include London’s Olympic Aquatics Center and the Heydar Aliyev Center in Azerbaijan.

The museum in Cincinnati was among the first.

The history of the CAC dates back to 1939 when it was founded by three women — Betty Pollak Rauh, Peggy Frank Crawford and Rita Rentschler Cushman.

The Modern Art Society, as it was called, initially operated out of a makeshift office comprising a letter file and a portable typewriter in “whichever living room was available,” according to the CAC website. They later moved to a gallery space in the basement of the Cincinnati Art Museum in Mount Adams.

None of the CAC’s founding trio had much museum experience among them. Still, they shared a desire to bring world-class modern art to area residents.

The Modern Art Society became the Contemporary Arts Center in 1956, despite the “center” lacking a true dedicated space.

It moved several times over the years to a series of semi-permanent spaces across downtown.

The CAC Board of Trustees discussed for years finding a permanent, standalone space that would reflect their mission. The idea gained traction in the mid-1990s, leading to the purchase of a small plot of land at the corner of Sixth and Walnut in 1998.

That same year, the board reviewed over 3,000 design submissions worldwide. They whittled the list down to three, including well-respected architects Daniel Liebeskind and Bernard Tschumi. They ultimately went with Hadid.

Construction started in 2001 and the new space opened in spring 2003.

Going with Hadid was somewhat controversial, according to Edward George Mitchell, the director of the School of Architecture and Interior Design at the University of Cincinnati.

There hadn’t been many museums in the U.S. designed by a woman, let alone someone who looked like her.

“There were people who were not happy about giving the commission to a Middle Eastern Muslim woman at the time,” Mitchell said. “Selecting Hadid from the project was really pretty significant on a lot of levels.”

Before coming to Cincinnati, Mitchell taught at Yale University for nearly 20 years. His time there overlapped with Hadid’s, then a visiting professor.

After studying mathematics at the American University in Beirut, Hadid moved to London to study at the Architectural Association, one of the leading architectural centers in the world.

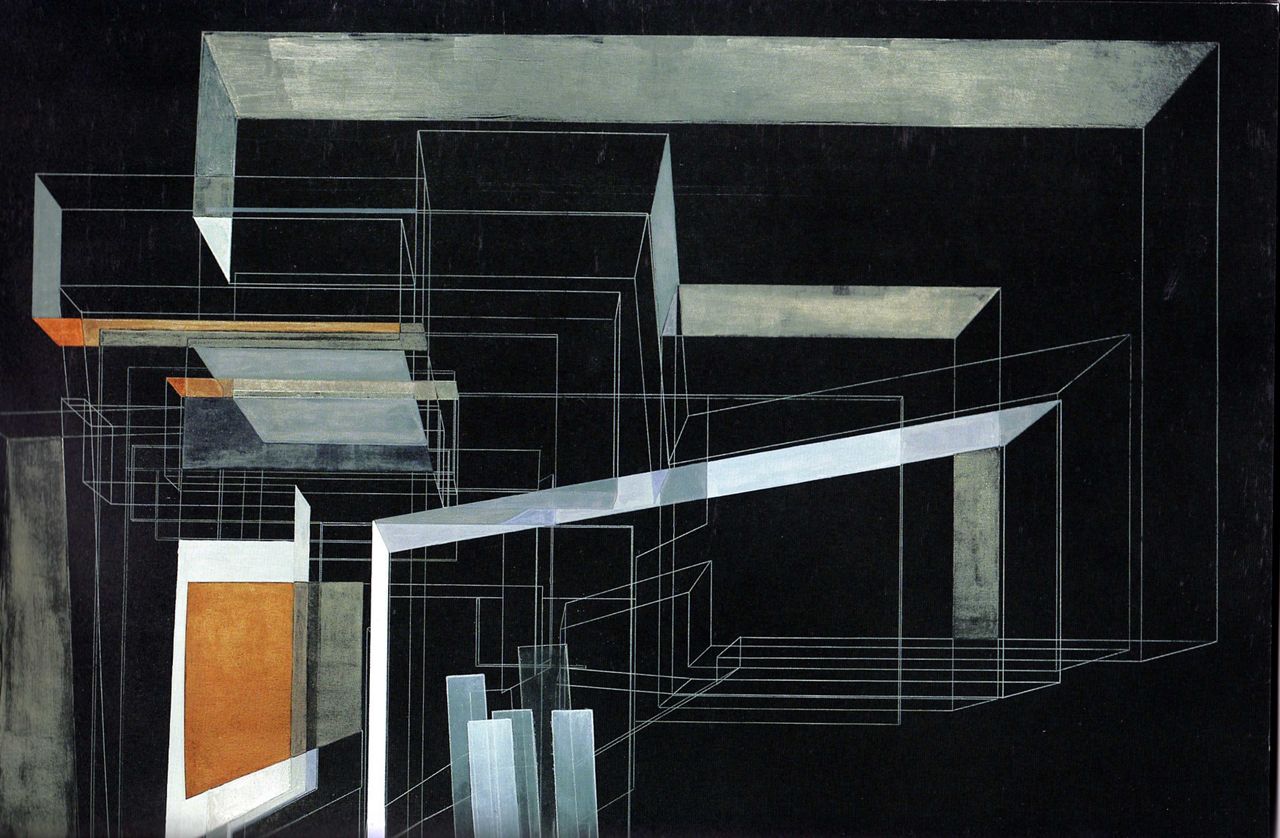

Hadid became known for aggressive geometric designs, earning her the nickname the “Queen of the Curve.” Much of her work emphasized a sense of fragmentation, instability and movement associated with the deconstructivism movement.

Deconstructivists aim to “destabilize the look of a building” to the person viewing it, Mitchell said. That’s done through design choice, like the manipulation of angles and tinkering with where walls hit the ground. It’s a way to take structure out of expected “vertical and horizontal alignments,” he added.

Hadid’s first major project was the Vitra Fire Station (1989–93) in Weil am Rhein, Germany, which used a series of sharply angled planes to create a structure meant to resemble a bird in flight.

“It’s often difficult for somebody who is a ‘paper architect,’ who did such fantastic drawings like she did, that they wouldn’t work out as an actual building,” Mitchell said.

The CAC, formally known as the Lois & Richard Rosenthal Center for Contemporary Art, helped solidify her reputation as one of the foremost and innovative architects in the world.

The design features a vertical series of cubes and voids on the exterior of the building. The street-facing side has a translucent glass facade that invites passersby to observe the goings-on inside.

The building gently curves upward after the visitor enters the building. Mitchell said you can see in that building where Hadid was trying to continue the street up and sweep it up through the backside of the building.

He said the goal was to “bring the city into the museum,” to keep it from being an elitist “enclave that museums can sometimes represent.”

Some of that curve was obscured a bit in 2015 when the CAC renovated the first floor to make the lobby more inviting for guests. They added new seating and a restaurant. Despite the changes, Mitchell said he still feels the building functions as Hadid intended.

“Contemporary art would have some interest in breaking down traditional boundaries and things like that, so it fits well with the building,” said Mitchell.

Bringing Hadid’s design to life wasn’t an easy feat. Primarily because there weren’t many like it built, and also the physical lot wasn’t particularly large.

“In a limited footprint, she was able to do quite a bit. I mean, the staircase that leads up to the galleries is pretty great,” Mitchell said.

To fully appreciate Hadid’s work, a person has to walk through the space to grasp the architectural intention. The CAC does its best to utilize every square inch of space for art exhibitions, often wrapping collections, like a pathway to the next display.

Hadid unexpectedly died of a heart attack in 2016 at age 65. To this day, buildings, like the CAC, serve as monuments to her brilliance. Her name will be forever associated with the museum’s history, admirers noted.

Hardin-Klink was so impressed with the CAC during her first visit in 2003 that she wanted to be a part of it.

“I had just graduated from college with a sculpting degree and being young and inspired, I was like, ‘I want to work here’ so I left my resume at the front desk,” she said.

Hardin-Klink began working for the CAC in 2013. She managed the family and school programs and started their teen and homeschool programs. Now she leads all creative learning programs, which are a major part of the museum’s mission.

The museum has had a full-time education employee since 1978 and created its children’s learning program a year later.

“Especially when dealing with contemporary art, education is important,” Hardin-Klink said. “The artists that we work with are, for the most part, still living and they’re making art about the world around us. Sometimes, it can be quite conceptual, so it’s great to have education there to help make those connections.”

Currently, the building is undergoing a multimillion-dollar renovation of its sixth floor to convert its UnMuseum into a new 10,000-square-foot creativity center. When completed this summer, the learning space will be available to artists of all ages.

While not always photorealistic, Hardin-Klink said contemporary art is “highly relatable” because it focuses on current events and “the world around us.” The themes reflect what people see on the news and on social media, she added.

One of the CAC’s goals is to engage the community and help open minds. One way it has tried to do that is to become more accessible.

While the building’s design aims to link the museum to the city, its administration wants to better connect with the residents. They, too, are trying to make the museum less of an “enclave.”

The CAC hosts regular programming to engage residents for special events. They’ve also tried to ensure the museum is available every day. One way they’ve done that is by going free.

They accomplished that in 2016 thanks to a group called “The 50,” a collection of residents who contributed the funds to cover necessary operations.

One of “The 50” is Michelle D’Cruz, a graphic designer and multidisciplinary artist. She became a member because she believes in the importance of making sure the “arts are publicly and widely accessible.”

“I didn’t grow up going to museums and galleries or seeing the incredible work of artists who look like me,” said D’Cruz, owner of Cincinnati-based MDC Design Studio.

“I want my children and others just like them to grow up seeing that the artistic community includes voices like their own, and is a welcoming space for all to participate, learn, and explore.”

The CAC’s commitment to engaging the community has led to what D’Cruz believes is a “staggering increase” in the local desire to promote the value of the arts.

Switching to free admission made the museum more accessible and led to a 73% increase in visits by young adults and families. Overall, attendance has tripled to nearly 160,000 visitors annually.

You could say they’ve rolled out the red (urban) carpet.

“Over the years, I’ve witnessed a broadened focus on the type of work that is shown in our city, both in gallery settings and beyond,” D’Cruz said. “There’s been an increase in attention to promoting the value and role of education within the arts community.”