CINCINNATI — As global temperatures rise, scientists expect climate change will affect some communities quicker and more harshly than others.

The issue has global as well as local implications. Areas already coping with geographic challenges, poor infrastructure, limited resources and post-industrial pollution expect those issues to worsen, often impacting low-income or otherwise disenfranchised communities.

Groundwork’s Climate Safe Neighborhoods project is pinpointing some of the most vulnerable spots in cities around the United States, including Cincinnati, where its Ohio Valley team is teaching locals how to take action.

Mohagany Wooten grew up in Cincinnati’s Lower Price Hill neighborhood without access to a lot of green. Concrete covers most of the ground, and even in spaces left open, Wooten said limited management left them overgrown and unsightly.

“This lot was full of nothing but grass and invasive species,” she said.

Now, Wooten has the tools to change the picture. As a part of the Groundwork Ohio River Valley Green Team, a paid team of neighborhood high school students, she’s spent the fall semester helping turn one of the empty lots into a green space for the neighborhood.

“So we can add more flat space for flowers and trees, maybe a little path,” she said.

Wooten hopes it will add a little color to the neighborhood, making the community brighter, but besides aesthetics, Groundwork expects the lot to make a bigger difference, helping to make Lower Price Hill a “climate-safe neighborhood.”

Groundwork is a national network of local community organizations focused on issues of environmental justice.

According to Sophie Revis, the Ohio River Valley’s climate resilience director, that means educating local communities about environmental inequalities inherent in their neighborhoods.

“Environmental justice is about righting those wrongs and providing access to the procedures where those decisions are made,” she said.

Revis said environmental inequality is not born in a vacuum — it’s systemic. She said history reveals city and state policies have worked to protect certain communities from environmental fallout while those without a seat at the table bear the brunt of it.

To see it in Cincinnati, Revis said all you need to do is look at where the green space is.

“Often a lot of white and affluent neighborhoods have more parks, less street-level air pollution, and more trees,” she said.

As a part of Groundwork USA’s Climate safe neighborhood project, the Ohio River Valley chapter has been mapping the areas in Cincinnati most vulnerable to climate change, adding particular focus to Lower Price Hill and its history.

Lower Price Hill sits in the Mill Creek Valley just across I-75 on Cincinnati’s near-west side. An urban and historic neighborhood, its population peaked in the post-World War II era as large groups of Black and Appalachian migrants moved to the neighborhood to fill vacancies at manufacturing jobs.

Decades later though, that industrial history would take a toll. The neighborhood’s median household income has historically lagged behind income levels across Cincinnati, while environmental hazards concentrated in the valley.

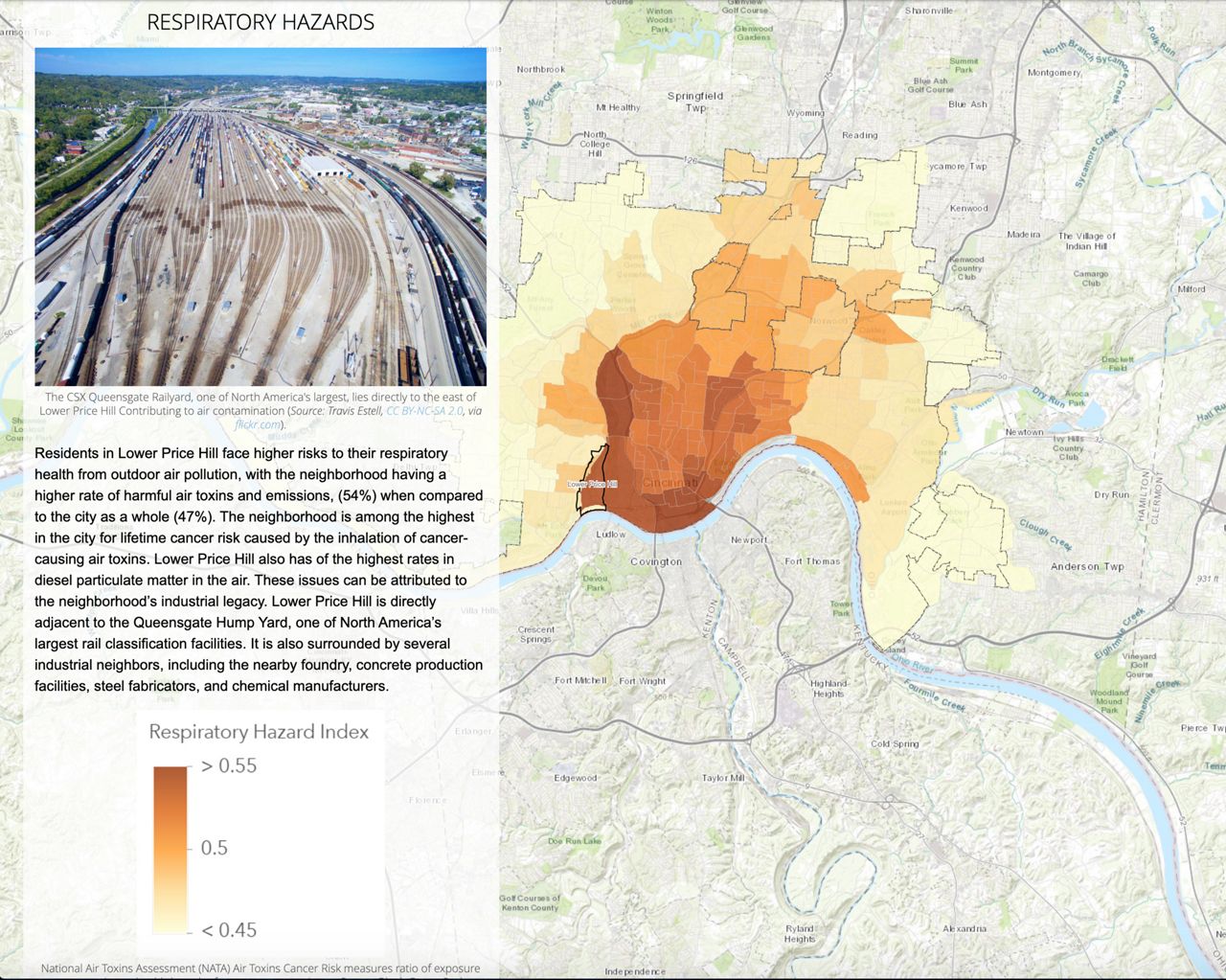

According to the National Air Toxins Assessment, Lower Price Hill has some of the highest concentrations of air toxins in the city, leaving its residents at a higher risk for cancer and other respiratory illnesses.

Sarah Morgan, Groundwork Ohio River Valley’s geographic information systems manager, said getting this data together on the same map provides context to the issues neighborhoods like Lower Price Hill are facing and why.

“We’re able to really show or visualize how different city policies — like redlining like zoning — have impacted not only the urban form of cities but the residents at varying extents,” she said. “We’re visualizing and telling the story of the neighborhoods that maybe are not necessarily equipped to prepare for climate change-related issues.”

Morgan said the maps also reveal intervention strategies. Higher surface temperatures and pollutants are concentrated in neighborhoods with little tree canopy and a saturation of impervious surfaces, so Groundwork is focusing its local efforts on changing the face of these neighborhoods at the street level.

Revis said as simple as it sounds, planting trees reduces localized air pollution and adds more shade to a neighborhood helping cool the area down. For Revis, it’s also an easy jumping-off point to help engage the community on issues of climate change.

“[We can make a difference] without getting into things like the ice caps are melting and the wildfires out west. It’s about issues that already are well familiar with, are living with on a daily basis and making that connection to climate impacts,” she said.

Groundwork wants its projects to be collaborative and empowering for the neighborhoods they work with, so Revis said it's essential they involve community voices in both the planning and intervention processes. The Green Team allows neighborhood youth to take an active role.

“It’s kind of nice knowing that I contributed,” Wooten said.

Green spaces like the one she and her fellow green team members are helping build reduce impervious surfaces in the neighborhood and help mitigate flood concerns, while the fruit trees they’ve planted on the edge of the plot will help provide a sustainable source of fresh healthy food.

Wooten said future projects will involve planting trees along neighborhood sidewalks and potentially adding cooling stations at bus stops.

Revis acknowledges these changes are not complete solutions for climate change, but she hopes as global temperatures rise, these mitigation strategies help communities like Lower Price Hill prepare for a warmer future.

Along with Cincinnati, seven other cities have joined the Climate Safe Neighborhoods project, including San Diego and Yonkers, New York.