CINCINNATI — It's safe to say that everyone has been affected by the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks in one way or another. Even those born after the events in 2001 have had their life shaped.

Few people have experienced the past two decades quite like Muslim Americans, however.

What You Need To Know

- "Islamophobia" predates 9/11, experts say, but the terrorist attacks in New York brought it to new levels

- There was a 1,600% increase in anti-Muslim hate crime incidents in 2001, per the FBI

- CAIR works to promote a positive image of Islam and Muslims in America

- Muslim population growth in the U.S. has led to more representation in the U.S. Congress

On Sept. 11, 2001, 3,000 people were killed, hundreds more injured when members of the terrorist group al-Qaida — which preached a radicalized form of Islam — hijacked several planes and used them as weapons.

Two planes crashed into the World Trade Center towers in New York City, toppling the buildings often referred to as the Twin Towers. A third plane flew into the Pentagon. Another, United Airlines Flight 93, was headed toward Washington, but was brought down in a field in Pennsylvania after passengers and crew members fought back.

"Discussing 9/11 is extremely important, it is a part of our history ... it's a very personal history for so many of us, just as imporant is a teacher’s responsibility to be aware of the Islamophobic context that is often correlated with 9/11," said Afaf Nasher, the executive director of New York chapter of the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR).

Since being founded in 1994, CAIR has worked to promote a positive image of Islam and Muslims in America and provide a voice for that population. They aim to give political and social support to American Muslims who've historically lacked national representation.

Following Sept. 11, the United States committed to a "war on terror" that yielded physical disputes in multiple countries in the Middle East — Afghanistan and Iraq. It also led to personal attacks against Islam and practitioners of the faith in the United States and around the world.

In the past 20 years, Muslims, and those perceived as Muslim, became targets of hate, according to CAIR.

Muslim religious leaders and organizations in the United States immediately denounced the attacks. But in some cases, distrust and hatred began to build among many Americans toward Muslims and even the religion of Islam.

"We have had now full grown adults who grew up in the shadow of 9/11 saying that it was commonplace for them to be called 'terrorist' by their peers at school," Nasher said.

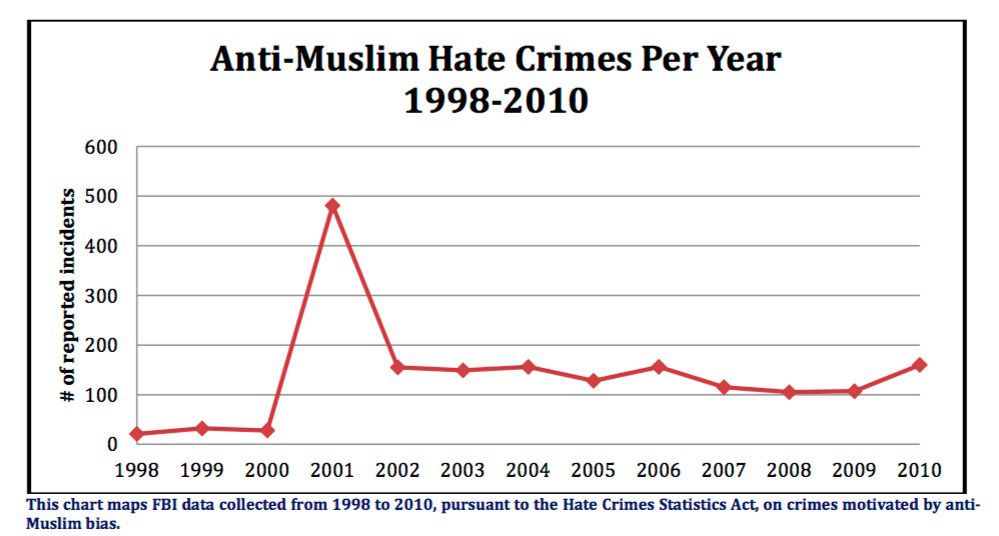

The FBI reported that there was a 1,600% increase in anti-Muslim hate crime incidents in 2001. And those numbers continued to balloon in the years that followed.

In the first six years after 9/11, the Department of Justice investigated more than 800 incidents involving violence, threats, vandalism and arson against persons perceived to be Muslim or of Arab, Middle Eastern or South Asian origin.

The DOJ prosecuted 50 defendants in 37 different cases, according to the 2011 report. Forty-five people were convicted.

The agency also investigated several civil cases to address unlawful discrimination on the basis of religion or national origin. That included things like the harassment of children in school.

The report shows that from 2001 to 2011, the DOJ opened "more than 28 matters" involving efforts to interfere with the construction of mosques and Islamic centers.

“This kind of stereotyping and hate runs counter to the basic values of equality and religious liberty on which this nation is founded. We must never allow our sorrow, our anger at the senseless attack of 9/11, to blind us to the great gift of our diversity in this nation. All of us must reject any suggestion that every Muslim is a terrorist or that every terrorist is a Muslim. As we have seen time and again – from the Oklahoma City bombing to the recent attacks in Oslo, Norway – no religion or ethnicity has a monopoly on terror," Deputy Attorney General James Cole wrote in that report.

And the anti-Muslim sentiment is not just a post-9/11 response; the Islamaphobia has continued throughout recent years.

CAIR said that from 2014-2019, their various chapters across the country recorded a total of 10,015 incidents of that kind of bias.

During the presidency of Donald Trump, the administration imposed a travel ban in early in 2017 that many saw as anti-Muslim. The latest version of the ban affected travel from seven majority-Muslim nations – including Iran, Somalia, Yemen, Syria and Libya – in addition to North Korea and by some Venezuelan government officials and their families, according to the Associated Press.

Between 2016 and 2020, approximately 60% of American Muslims reported experiencing religious discrimination, according to the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding (IPSU).

IPSU's data showed that 42% of Muslims parents reported that at least one of their children had been bullied in the past school year because of their religion. The report stated that one-quarter of those cases involved a teacher or school administrator doing the bullying.

"Unfortunately, we often receive complaints of anti-Muslim bullying and harassment," said Whitney Siddiqi, with CAIR-Ohio. "That's why we work to educate teachers and administrators about the Muslim community and Islamic practices so we can create a safer atmosphere for Muslim students."

While struggles do remain, Muslim Americans some strides have been made.

President Joe Biden signed an executive order in March to reverse the travel ban. He referred to the ban as "a stain on our national conscience" and "inconsistent with our long history of welcoming people of all faiths and no faith at all."

The number of Muslims living in America has also grown considerably in the past 20 years, according to the Pew Research Center.

The organization estimated that Muslims now make up about 1.1% of the United States population, or about 3.85 million. But that's up from about 2.35 million in 2007, per Pew.

Muslims have also, for the first time, started to have formal representation in Washington, D.C. In 2007, Keith Ellison was elected to the House of Representatives. He became the first Muslim sworn in as a member of Congress.

Ellison made the decision to leave Congress to run for, and be elected the attorney general for Minnesota. But since his election, three other Muslims have been elected to the House; Rep. Andre Carson and two women, Reps. Ilhan Omar and Rashida Tlaib.

One area where there is still room for growth, and more accurate, is popular media, according researchers with the Annenberg Inclusion Initiative out of the University of Southern California.

The research team recently released the report, "Missing and Maligned: The Reality of Muslims in Popular Global Movies." The team looked at 200 popular films made between 2017 and 2019 in the U.S., the United Kingdom, Australia and New Zealand. Of them, only six had a Muslim in a co-leading role, and only one of those was a female, according to NPR. Fewer than 2% of the more than 9,000 speaking parts went to Muslims.

The report also found that often the only depictions of Muslims are of terrorists or other stereotypes. Some movies, like "Aladdin," only show Muslim characters from the past, the report found.

Oscar-nominated actor Riz Ahmed told NPR that the "the extent of Muslim erasure, the extent in particular of erasure of Black Muslims, and Muslim women, it was really shocking."

Further and better representation are good first steps toward making progress. Nihad Awad, CAIR's executive director said in July, that there's still work to do on that front.

“I can tell you that many Muslims around this country and around the world, those who live as minorities, they started to feel that Islamophobia is part of normal life. It should not be, and we should not accept it,” Awad said.