CINCINNATI — City Council member Chris Seelbach announced earlier this month plans for a charter amendment that would raise funds to support local affordable housing.

Revenue from the proposed 0.1% earnings tax increase (from 1.8% to 1.9%) would go toward the construction, development or maintenance of housing units in Cincinnati. He believes the levy would generate approximately $170 million over the next nine years.

A 2017 report by Xavier University's Community Building Institute showed a 40,000-unit gap in Hamilton County.

But what does "affordable housing" actually mean? And who benefits from it?

What You Need To Know

- Council member Chris Seelbach proposed a charter amendment to raise funds for affordable housing

- Affordable housing aims to ensure people aren't "cash burdened," keeping housing costs under 30% of their income on rent or mortgage

- There is roughly a 40,000-unit affordable housing gap in Hamilton County

- An "affordable" 1-bedroom apartment in Cincinnati is $696; an affordable 2-bedroom is $916

Margaret Fox, the executive director of the Metropolitan Area Religious Coalition of Cincinnati, said there's a lot of misconceptions about affordable housing or assistance programs like the Housing Choice Voucher credit.

Some of that confusion revolves around who needs and qualifies for help.

It includes people who are experiencing homelessness or may be out of work. Then there's also a lot of people working pretty traditional jobs who are eligible.

School cafeteria workers, janitors, school paraprofessionals, store clerks, home health care workers, and staff at the local recreation center are among those who could benefit.

They may work 9-to-5 but don't earn enough money to pay the going market rate for a house or apartment.

It could be the hardest for parents.

The federal government considers housing affordable when a person or family needs to spend no more than 30% of their income on it. That price tag includes rent or mortgage payments as well as utilities.

Spending more than that may make it difficult for a person to pay for other everyday needs — food, transportation and health care. That's called being "cost burdened," according to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Those spending 50% or more are considered “severely cost burdened.”

The CBI report said there to be about 44,000 cost-burdened families in Greater Cincinnati.

One of the ways to look at the relative affordability of a home or rental property is the Fair Market Rent rate calculated by HUD. Cincinnati's area spans parts of Ohio, Kentucky and Indiana.

HUD uses FMR to set payment standards for federal housing assistance programs. The rate includes core utilities, like water and power. It does not include optional services like cable and internet.

On average, a one-bedroom in the Cincinnati region costs $696 per month, according to RentData.org. The average two-bedroom goes for $916. Both numbers are slightly higher than the rest of Ohio.

Using FMR as a guide, a person would need to earn $17.61 per hour, working 40 hours per week, to afford a two-bedroom apartment. That translates to about $36,628 per year.

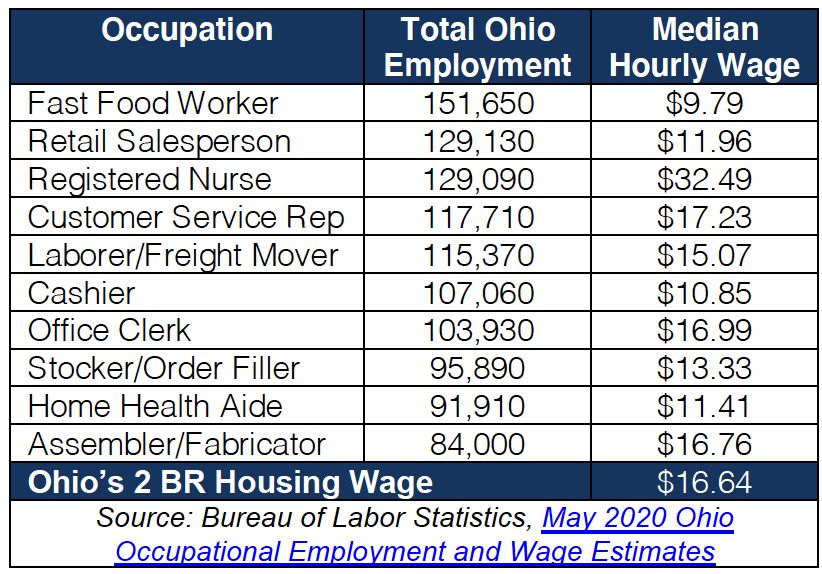

By that standard, the majority of employees working in the 10 most common jobs in Ohio couldn't afford it, based on data from the Out of Reach 2021 report. The National Low Income Housing Coalition and the Coalition on Homelessness and Housing in Ohio published the report on Wednesday.

Only registered nurses would earn enough on an hourly basis ($32.49) to afford a two-bedroom apartment using the FMR figure.

The minimum wage in Ohio is $8.80 per hour. At that rate, a person would need to work more than 80 hours a week to afford a one-bedroom at the monthly FMR rate ($698). Conditions have only gotten worse because of COVID-19.

"But Ohioans working in many other widely available jobs – retail salespersons, cashiers, restaurant and hotel workers – were already struggling before getting laid off or downsized during the pandemic,” the report reads.

COHHIO executive director Bill Faith said the situation facing Ohio’s tenants is "undoubtedly worse" than the report shows because they collected data used in the report prior to the pandemic.

“The spike in home prices is driving the cost of rents higher in many areas, making the affordable housing shortage even worse for people who were already struggling to pay rent,” he said.

Relief measures, like Emergency Rental Assistance and eviction moratoriums, have helped prevent homelessness caused by COVID-19. But those efforts don’t get to the heart of the affordable housing issue.

Brian Griffin, a housing rights advocate, said establishing affordable housing solutions will provide stability for individuals who are “literally one paycheck, a bad morning really, away from being homeless."

"This is an issue affecting people all over the map. I mean that literally and figuratively," he said.

"There are all kinds of various reasons why, all kinds of reasonable reasons why people may need affordable housing ... These are just people doing their very best, many of them working full-time jobs just trying to put food on the table for their families," He added.

Seelbach is still working on his proposal. He planned to use the city council's six-week summer recess working with the community to fine-tune it.

A vote by the city council would likely take place in August. If it gets six votes, it will make it to the November ballot.