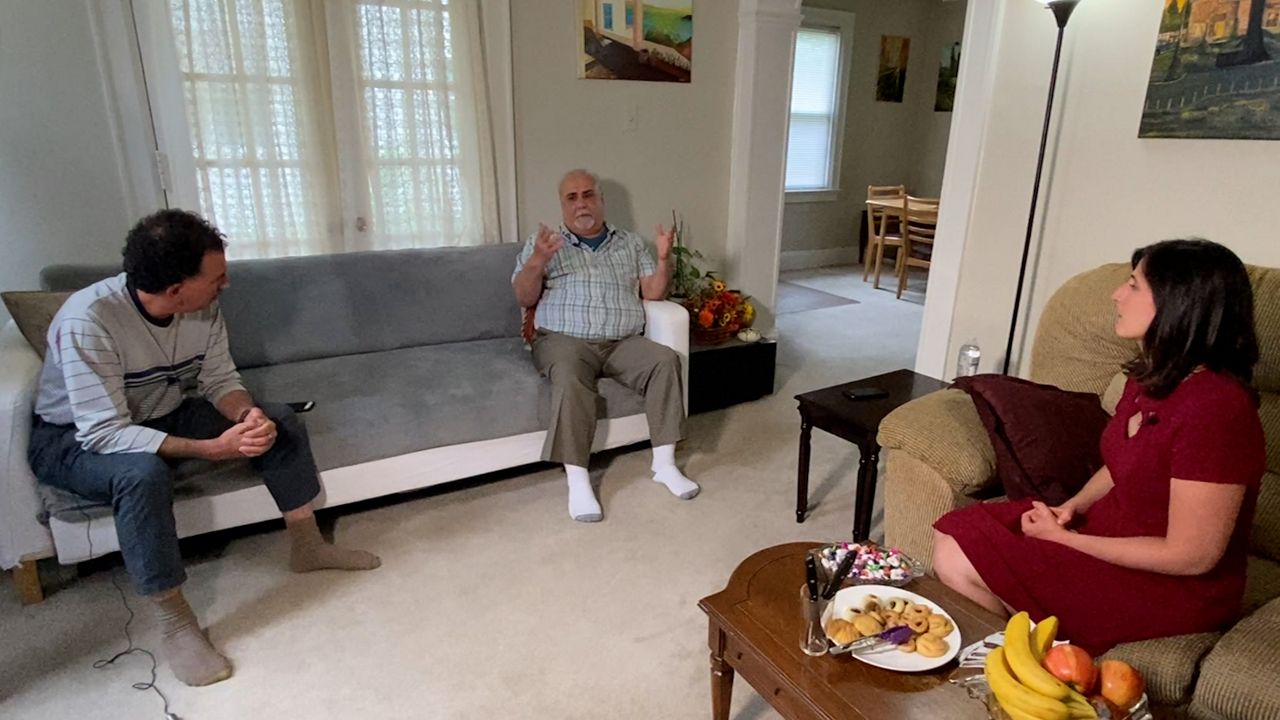

CINCINNATI — The smell of freshly poured coffee and cardamom hangs in the air as Mamdouh Darouich and his wife prepare plates of treats for their guests. This time, it’s a representative from Catholic Charities of Southwest Ohio and an interpreter, to help prevent any misunderstandings.

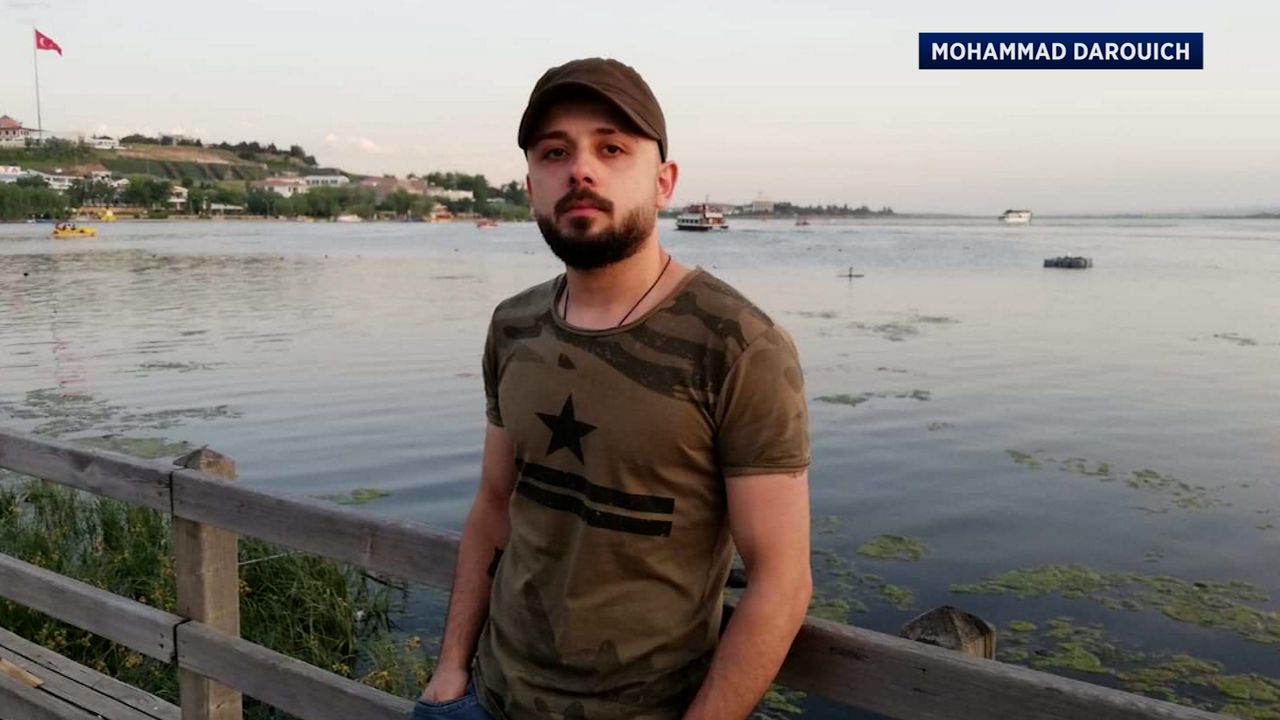

The family is awaiting important news they don’t want tinged with any confusion. After four years of waiting, their eldest son Mohammad has been approved to join them in the U.S. by mid-June.

The Darouich family arrived in Cincinnati in 2017 as Syrian refugees. Darouich said his son, Ahmad, came first. Three months later, the parents and younger brother and sister followed as a group. Mohammad, 32, remained in Turkey, where the family sought asylum.

Darouich said the family expected him to come a few weeks later. Four years later, they’re still waiting.

“He is alone he wishes to be with family,” Darouich said.

The family hasn’t felt safe and whole since they lived in Aleppo. Once the largest city in Syria, it became the site of one of the largest and longest battles during the country’s ongoing civil war.

“After the war, the life was miserable,” Darouich said. “No food. No water and whoever had money after one year, everything is gone.”

Two years after the war broke out, the family fled to Turkey to avoid the conflict.

“We left everything the house, everything, just our clothes,” Darouich said. “Whatever money have we took it to Turkey.”

Once the family was granted asylum, Darouich said they moved to Ankara where he found a job and maintained a modest living in the Turkish Capital city. The family lived there for four years as the United Nations granted them refugee status and considered options for permanent placement, eventually choosing Cincinnati.

In the meantime, the U.S. was entrenched in a debate about whether to admit Syrian refugees at all or whether it would compromise the nation’s safety and stability.

During the Obama administration, the number of Syrian admissions into the country was rising, while President Donald Trump campaigned on reducing the number of refugee admissions and banning travel and immigration from several mostly Muslim countries. A part of his “America First” ideology, he argued Syrian refugees would be potentially dangerous to the country and would make it more difficult for U.S. citizens to find jobs.

Others including then Ohio Governor John Kasich and Cincinnati Mayor John Cranley called for fewer Syrian admissions to the State, though Cranley later walked the statement back, claiming Syrians are welcome if they’re properly vetted by the U.S. government.

When asked about the anti-Syrian, anti-Muslim sentiment at the time of his arrival, Darouich said his family still felt welcomed.

“I’ve been here for four years and I haven’t seen anyone asking me why you are here?” He said. “There is a lot of people who don’t like strangers and this is very minor people and this is their opinions.”

When Mr. Trump took office, however, his family felt the direct impact of the shifting U.S. policy on refugees and immigration.

In Obama’s final fiscal year in office, Pew Research reports the United States resettled 12,587 Syrian refugees. By 2017, U.S. took in less than a quarter of that number and by 2018 the U.S. resettled a total of 62 Syrian refugees.

Darouich and his family were the last to come to Cincinnati. They found out weeks after they arrived Mohammad wouldn’t be joining them.

"It’s a problem, I don’t know how to solve it,” he said. “My son is always asking me, ‘Why are you not with us? Why am I not with my other siblings?’”

In southwest Ohio, Catholic Charities handles most of the logistics surrounding refugee resettlement in the region.

They help families like the Darouiches find housing, enroll their children in school, take language learning classes and find employment opportunities.

Annie Scheid, the executive director of refugee resettlement for the agency, said she took the position with Catholic Charities in 2017, as they were ramping up to welcome more refugees than ever before.

“Folks from all over the world,” she said.

For the past four years, she said they were averaging about 200 to 250 refugees in the Cincinnati area. When 2017 began they were expecting more than 450. That year they took in 279, then the number declined rapidly.

Every year, the Trump administration lowered the cap determining the maximum number of refugees the states could take in, and every year, Scheid said her department had less and less to do.

“We went from the presidential determination for 2017 of 110,000 to this current year at 15,000,” she said.

She said Catholic Charities lost 11 staff members dedicated to refugee services over the past four years as the department saw fewer and fewer arrivals.

Then in May, after pressure from Democrats, President Joe Biden announced another change in policy. The United States would now lift its refugee cap to 62,500, allowing agencies like Scheid’s the chance to prepare for their first increase in cases in years.

“We at least know there is some light at the end of the tunnel, that the opportunity is there and the plan is to rebuild,” she said. “It’s just a matter of when and maybe waiting a few extra months before that can start happening.”

Scheid said the pandemic still adds another layer of difficulty to the work, but she said everything starts long before the refugees ever board the plane.

In their asylum countries, the U.N. is screening them both for security and placement reasons but also for communicable diseases, while groups like CCSWOH prepares to help the refugees become self-sufficient within 90 days of arrival.

One of the first cases she hopes to work through is Mohammad Darouich’s.

The U.N. approved the eldest son for placement in the United States, now his family hopes to see him fly in on June 11.

“I was hoping. It makes me very, very happy,” Darouich said. “But it’s uncompleted happiness.”

As of June 8, the plans are in set, but Scheid warns working with the refugee system can be unpredictable.

“Until we actually have the refugees standing in front of us, we don’t know if they’re going to come,” she said.

Due to pandemic restrictions as well, Mohammad would have to quarantine for ten days upon his arrival in the United States.

After four years of waiting though, the Darouich family said it’s hard not to hope. Mohammad’s English is the strongest in the family and they have no doubt, he’ll find success in the United States. Most importantly though, Darouich said the family will finally feel safe together.

“It’s going to be happiness and freedom here in the USA,” he said.

Refugee resettlement remains controversial. Even the Biden administration initially refused to raise the refugee cap, claiming the country was already overwhelmed with pandemic recovery and the crisis at the U.S.-Mexican border.

With more than 26 million refugees seeking resettlement worldwide, however, Scheid believes the United States has a responsibility to help however it can.

“We are not alone in this world,” she said. “We can do both.”