CLEVELAND — One Ohio family includes a mother-daughter bond that is unbreakable. It stems from the heart.

“I feel like with the trauma, you either bond strongly from that situation or it kind of tears you apart and we’ve definitely built a pretty strong bond from everything,” said Ashton Bell, 17.

Denise Bell and her daughter, Ashton, have a lot in common and have been through a lot together.

“Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy,” said Denise.

HCM is a rare heart condition they both live with. The disease can be hereditary and causes the heart to thicken and stiffen which can trigger cardiac arrest.

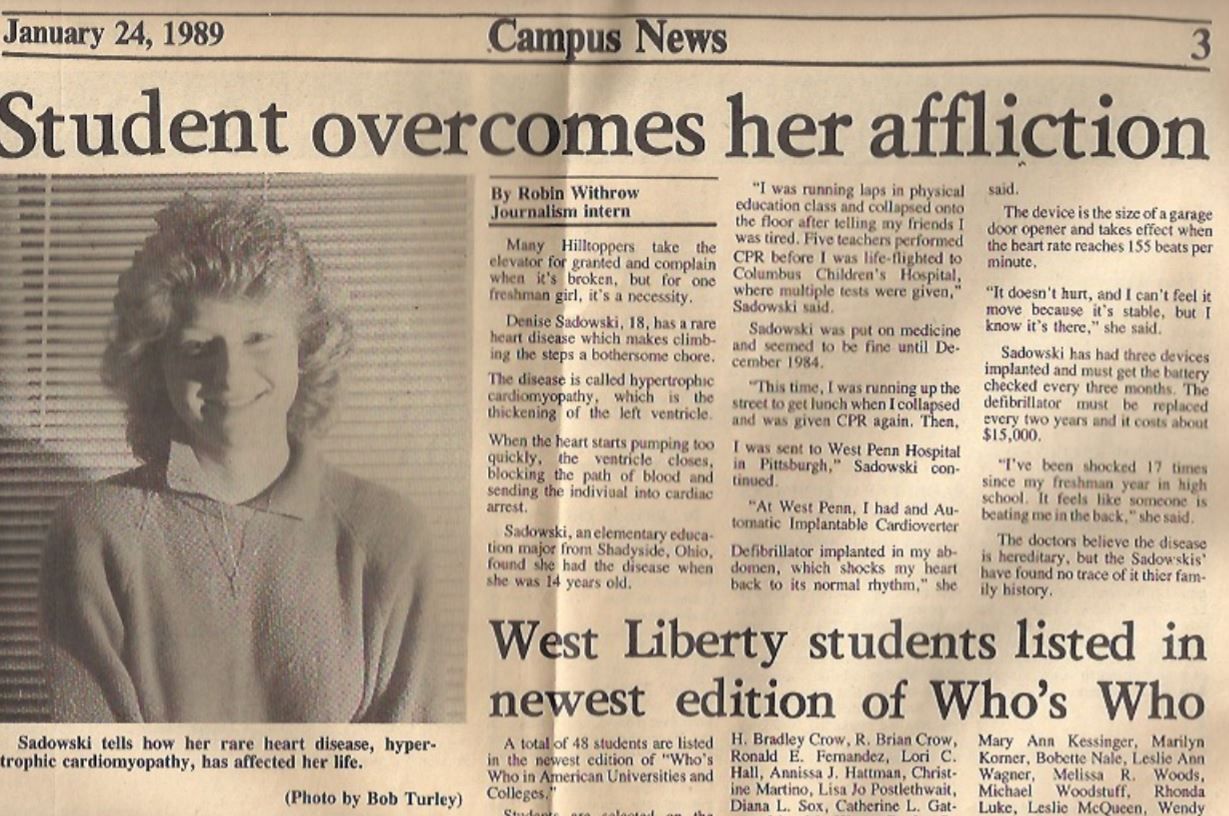

Denise’s battle began at age 14.

“When I went into cardiac arrest in gym class on Sept. 24 of ’84, I have no recollection of that. I only know what people have told me. They said I was running laps in gym and I just said 'I don’t feel right' and next thing you know, they said I had collapsed and went in to cardiac arrest," she said.

Denise would go into cardiac arrest 14 times by the time she turned 17.

“I just remember wanting to be normal like everybody else but also afraid to do anything," said Denise.

Contact sports and intense physical activity were out of the question.

A lot of trial and error helped her find the right medication, and Denise’s defibrillator seemed to stabilize things for nearly 20 years.

She married her high school sweetheart and doctors eventually gave them the OK to have a baby, but there was a 50% chance their child would also have hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

“She was our miracle girl. Once she was born, she was seven weeks premature," said Denise.

As Ashton grew up, Denise grew sicker and was in and out of the hospital.

“I grew up just being nervous for her and then being nervous for myself because I assumed since she had it that I would too,” said Ashton. “I’ve always had really bad anxiety about it.”

Ashton saw a cardiologist since birth and although she had no symptoms, she was diagnosed with HCM at age 12.

Thirty-four years and one day from her mom’s first heart event, Ashton went into cardiac arrest.

“I felt like I couldn’t get a breath of air to like fully grasp what had happened," she said.

Her freshman year of high school, Ashton had her own scary event in the gym. CPR and an AED device saved her life.

"It hit really hard, and I just felt guilt because she ended up with it," said Denise.

Ashton hasn’t had any issues since.

Her medication and defibrillator have been working well, but her mother’s health continued to decline. Denise’s heart failure was so severe that her only option was a heart transplant.

“For those last couple years, I felt like I wasn’t living. I was just existing," Denise said.

The surgery was successful in 2019, but the family went through a range of emotions leading up to it.

“I was just under the assumption that I was probably going to die. I never told them that, but that’s the way I felt," said Denise.

“I genuinely thought I was going to lose my mom," said Ashton.

The transplant saved her. Today, she’s better than ever.

“I had a second chance at life," said Denise.

Denise went from not being able to walk up the stairs, to crossing the finish line hand-in-hand and heart-to-heart with her daughter at the Akron Heart Walk.

“Best feeling in the world knowing — you know what, we’ve made it. We’re doing OK,” said Denise.

HCM is estimated to affect 1 in 500 people, but often times it goes undiagnosed.

Denise’s cardiologist, Dr. Wilson Tang of the Cleveland Clinic, said exciting things are happening now to create a more hopeful future.

“There are better and better medicines now. In fact there are some medicines specifically targeting these conditions to try to delay the progression. So we are actually developing pills to really specifically target, to delay the deterioration of the heart,” said Tang.

Research and technology continue to advance and a lot more is known about HCM now compared to when Denise was first diagnosed. In fact, she was one of the first in the country to have an implantable defibrillator.

Tang said heart transplants are not necessary for all patients with this kind of heart disease. It's more likely that they won't need one. He said the outcomes are relatively good for many people living with HCM.