OHIO — One year ago, on the first day of spring semester, Jan. 27, 2020, a Miami University of Ohio administrator answered a call from campus health — A student who had just returned from a trip to China and presented flu-like symptoms.

Parents anxious by the arrival of the virus in the U.S. were just starting to call university officials the week before with questions and concerns about student safety, said Jayne Brownell, the vice president for student life.

“Stories about the coronavirus were just starting to come out in the media. It was clear that there was something going on, specifically in Wuhan,” she said. “But it really wasn't on anybody's radar screen yet."

At 11 a.m., Brownell picked up the call from the student health director, who informed her a young man had come into the health service that morning with a travel history and symptoms in line with what officials knew about COVID-19.

The student had traveled to China with another Miami University student, who reported feeling some symptoms a week earlier that had gone away.

It was the first COVID-19 scare in Ohio, and the campus had two suspected cases and potentially numerous exposures.

The student with symptoms told student health he went to his 8 a.m. class before he came in to get checked out, Brownell said.

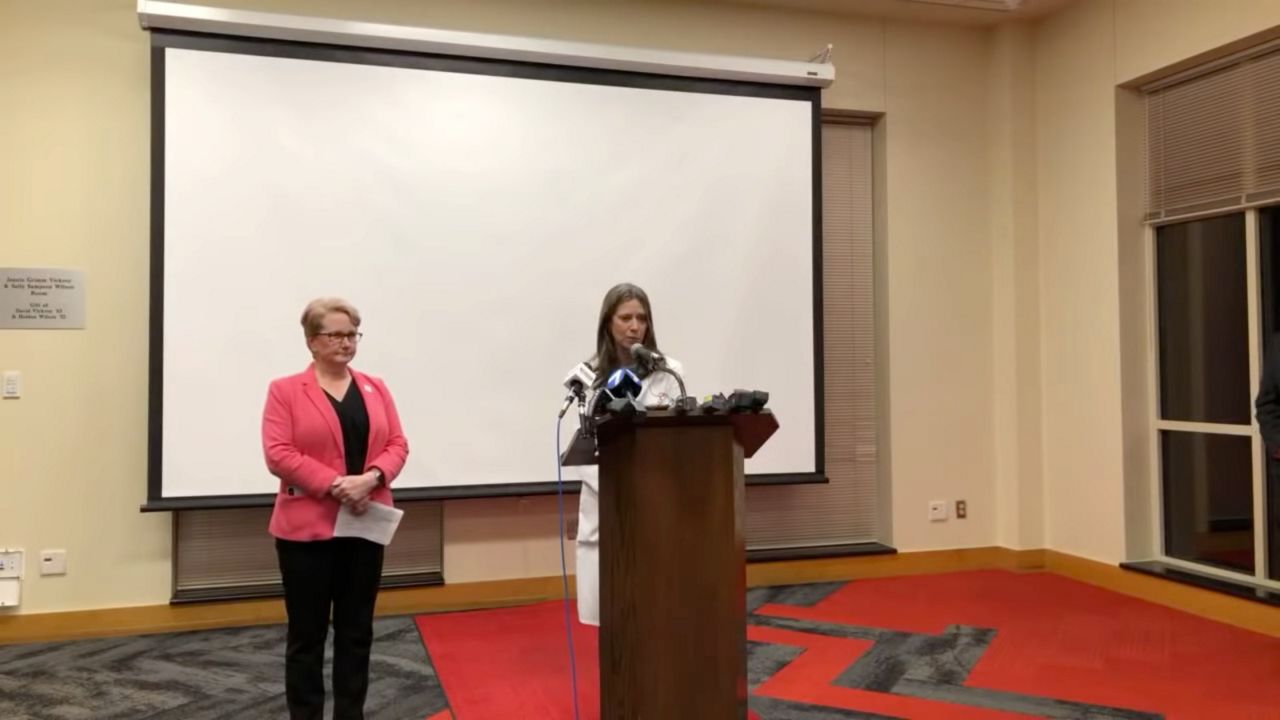

The next day, then Ohio Department of Health Director Dr. Amy Acton and her team flew and held a press conference at the university, where she assured the state’s residents her team was well-equipped for the challenge ahead.

“We stand ready. Ohio is prepared. We drill for this,” Acton said.

Brownell said the school felt supported, describing an “immediate vibe” the former health director brought to Oxford. It was a feeling that she was “on it,” and an air of competence and confidence, she said.

“It made everybody feel like, 'We've got this,'” Brownell said. “We felt very supported to have a physician walk in the door, who does public health, and say, ‘We're here to support you. What questions do you have?’ We could ask her and her team anything. And she took the time to guide us through.”

The students were tested and their samples sent off to a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention lab for processing.

At the time, it was one of only a couple of testing labs in the country. The possible cases were reported the same day the known global death toll entered triple digits.

Students and parents nervously awaited the test results. Administrators had questions of their own, Brownell said.

“Is this going to be a thing or isn't it? How big of a deal is it?” she recalled. “We didn't expect that, immediately, we would be managing this. Nobody knew how to do it yet.”

The students were quarantined in off-campus apartments, while state officials told the community the risk was still contained to anyone with a travel history to China.

“That week I remember just, like a group of us, in a room, writing, writing, writing, just trying to get as much information out as we could,” she said. “It was a very intense time — that we thought would be finite.”

Officials reported the symptomatic student was feeling better that Tuesday, Jan. 28.

Classes were not disrupted by the scare, but administrators were hard at-work preparing to respond in the event of positive results. In fact, they had a bit of a head start. In 2019, the school had reassessed its pandemic preparedness plan, revisiting lessons from H1N1, Brownell said.

On Feb. 2, the results came back negative. School officials said they would continue to monitor the students.

“We got the results and breathed a sigh of relief,” Brownell said. “But it really got the machinery starting for the state... It got the Department of Health to say, ‘OK, we dodged the bullet this time. The test came back negative, but that's not going to last. This is going to come up.”

While the test results were negative, the date still stands out in the history of the pandemic in Ohio. The new virus was still a great unknown, but Brownell said the Miami University scare put the whole state on alert.

The scare also prepared colleges for the future, as Ohio confirmed its first three cases outside Cuyahoga County on March 9, according to the Ohio Department of Health.

The day after on March 10, campus officials held a meeting with spring break coming up in three weeks.

That day, Kent State, Ohio State, Case Western Reserve, and several other Ohio colleges suspended in-person classes.

Officials were discussing just how disruptive it would be if classes were remote for a week or two after spring break to let students isolate. It seemed almost infeasible from an academic standpoint.

By the evening, the school had made a decision that distance learning would take effect the next day.

Gov. Mike DeWine then ordered all of Ohio's public, community, and private K-12 school buildings to close March 12. The closures and class suspensions caused a ripple effect through the state, as schools had to quickly shift gears and change plans throughout the next nine months.

As of now, many college students are still studying remotely, and Ohio's K-12 schools have hopes to return to in-person classes March 1. Schools have begun to receive their first doses of the vaccine — earlier than the initial date planned by the state. But with new variants popping up in Ohio and across the nation, it's possible academia will once again have to pivot.

In a press conference Tuesday, DeWine said while most schools are hoping to return to some normalcy, he warned that there's still many unknowns associated with the virus and the variants.

“The coronavirus is extremely unpredictable. We have a new ‘midwest variant’ of the virus, and we are concerned that it could become the dominant strain in Ohio. This variant is much more contagious,” DeWine said. "Please continue wearing masks.”