PUTNAM COUNTY, Ohio — In Putnam County, 1.3 of every 100 residents have tested positive for COVID-19 in the last two weeks — the highest local rate of infection Ohio has seen during the pandemic.

Regional hospitals that treat residents are filling up with COVID-19 patients. Worsening spread in Putnam County as well as neighboring counties, including a hotspot in Findlay in Hancock County, have brought a record numbers of COVID-19 inpatients to the local hospitals.

In the region, 27% of all hospital inpatients are individuals suffering coronavirus-related complications, and when it comes to intensive care beds, an even higher share of the people receiving care are COVID-19 patients, 33%.

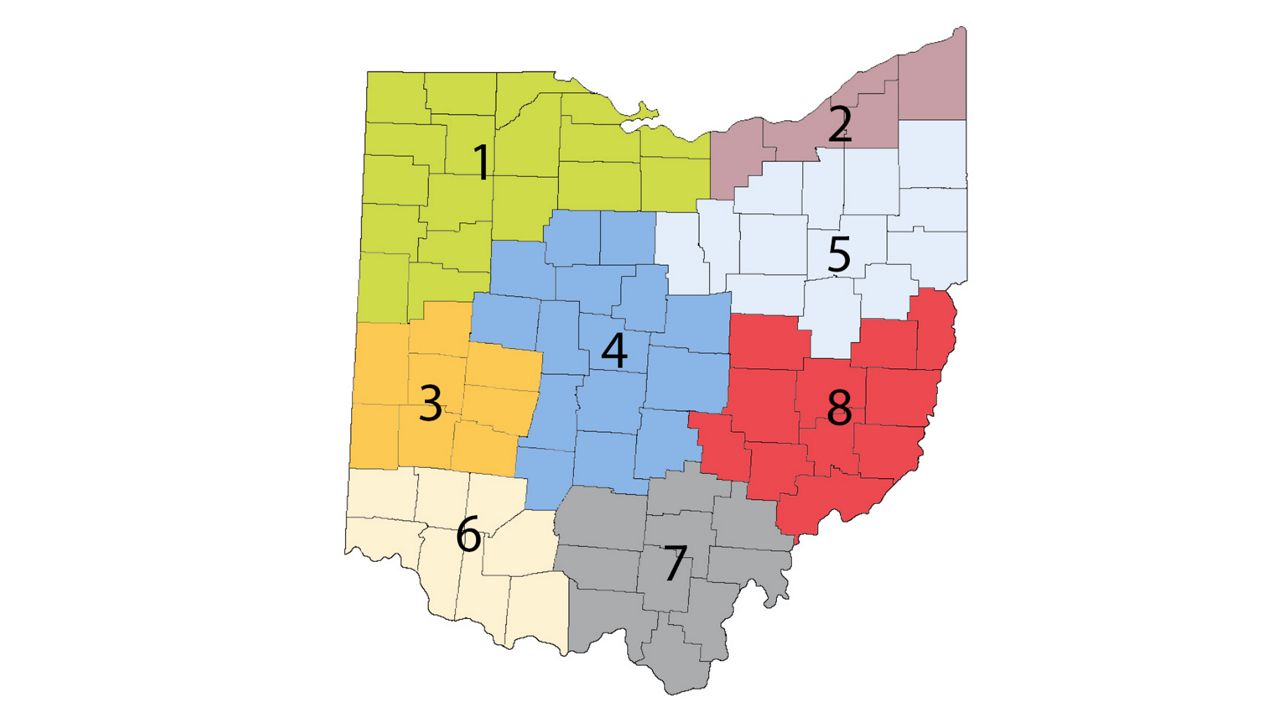

“This virus is burning strong throughout northwest Ohio,” Gov. Mike DeWine said Wednesday. Every county in the region is more than five times above the CDC’s criteria for high incidence.

Cases started to climb around Oct. 1 in Putnam County. The hospitals’ COVID-19 inpatients were at manageable numbers then, around 15 to 20 patients, but now the number of COVID-19 hospitalizations has quadrupled.

Surgery, medicine, ICU, and emergency room departments are seeing an influx of COVID-19 patients.

The small county’s 33,861 residents typically receive hospital care at Mercy Health St. Rita's Medical Center and Blanchard Valley Hospital, both in neighboring counties.

The state of affairs at the two hospitals offers a preview of how other regions may fare if their case numbers reach similar levels to those of Putnam County.

Northwest Ohio hospitals have postponed elective surgeries.

Officials are considering “alternative” models of care for treating more patients at once with less staff, which involves doctors sending patients home more quickly to free up bed space.

“One of the things we’re looking at is that we make sure we get people home as quick as we can,” said, Dr. William Kose, Blanchard Valley’s special projects vice president. “If they're stable, if they don't have to stay another day or two, that will free up a bed.”

Kose said hospital staff are “fatigued” from long shifts.

“Individuals that aren't sick have to pick up either extra shifts or overtime, leading to a fatigue factor. It's kind of a vicious cycle,” he said.

Hospital visitation has been restricted.

Health care workers themselves are becoming infected or exposed, reducing staffing levels.At Mercy Health St. Rita's Medical Center, “unprecedented volumes” of COVID-19 patients in need of care are being admitted, said Dr. Matthew Owens, chief clinical officer.

“We have been in the midst of quite a large surge, which has impacted our daily business and our daily provision of health care,” he said.

Health care workers at the hospital are “redeploying” in alternate rolls to meet the staffing challenges.

“Our ability to continue to exponentially grow these numbers is becoming extremely limited,” Owens said.

Blanchard Valley is considering different models for caring for more patients with fewer people, Kose said.

“We're having to consider alternative nursing models and alternative health care team models where we're having these teams take care of a larger and larger number of patients,” he said.Those models include taking advantage of beds in surgery and recovery rooms, adding non-traditional beds.

The hospital is looking at different avenues to add space at different sites if further bed space becomes needed.

But the biggest concern is workforce, not bed space.

The availability of traveling nurses is extremely limited as the country is setting records for hospitalizations, making it harder to bring in relief for overworked hospital staff.

Owens said St. Rita’s would in normal times be able to source health care workers through Mercy Health.

“Our ability to source staffing resources from our partnered hospitals has been extremely difficult,” he said.

Officials are particularly concerned about rural areas, which may have fewer resources and health facilities, and have shown to be ripe environments for the transmission of COVID-19 in Ohio in recent weeks.

Dean Meyer, mayor of Ottawa in Putnam, said residents should put politics aside and get to better mask compliance in order to curtail the rampant spread of the virus in the county. Meyer, who represents a conservative town in a county that supported President Donald Trump by among the highest margins in the state, said he is calling for more responsible behavior and better compliance with health guidance.

Explaining the high rates of spread in Putnam, Kose said rural residents felt like the virus was distant them after urban areas were affected the hardest in the first months of the pandemic.

“In Northwest Ohio, we didn't feel like we were going to get this. Putnam is not urban, it’s not the big city where there's a lot of people around.”

Owens said Putnam County is made up of small, connected communities, where the virus can seep in and spread at gatherings.

“If you were able to spend time in these communities, you would realize how supportive they are of each other, how close knit they are. And therefore they are at increased risk because of that sense of community,” Owens said.