COLUMBUS, Ohio — An inmate at the Pickaway Correctional Institution was recovering from a rough bout with COVID-19 when a confrontation with prison staff escalated in his dorm full of positive inmates. The next thing he knew, a prison staff member pulled out pepper spray and let “loose like there was no tomorrow.”

Dealing with the symptoms of COVID-19 is bad enough. "COVID-19 and pepper spray? Like torture," Dwayne Smith, 46, of Clermont County said.

“I thought that I was going to die,” he said. “I couldn't breathe.”

This incident is one of many scenes inmates recall from living through the deadliest COVID-19 prison outbreak in the United States. According to the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction’s latest update, 36 inmates and one staff member have died of COVID-19 at the prison.

The vast majority of the prison’s roughly 1,800 person inmate population contracted the virus. Some inmates say they tested negative only because they had already recovered by the time they were tested, but, officially, 1,452 inmates have tested positive and recovered. More than 100 staff members have tested positive.

When Smith was pepper sprayed in early April, the prison had yet to sound the alarm about the virus outbreak. He and many others had gotten very sick, but they were all undiagnosed at the time.

But some of the inmates had watched enough television news to know that the symptoms they were seeing – otherwise healthy men being unable to get out of bed for a week, for example, weren’t from the flu.

Hundreds of inmates were coughing, sneezing, and struggling to breathe.

The dorm-style prison has eight blocks that hold about 250 inmates. Each block contains five or six bays, which typically hold 44 or more inmates in a roughly 20 foot by 100 foot open room filled with rows of bunk beds.

“We were sitting ducks,” said Ryan Patterson, 29, of Belmont County.

Distancing was impossible in the bays. One inmate measured the distance to his neighbor on the right, who was 37 inches away, and to the neighbor on his left, 34 inches.

“Laying in my bed, I can reach out and touch the bed next to me on both sides and the one above me,” said another inmate, Timothy Stufflebean, 37, of Licking County.

Feeling helpless, inmates fashioned makeshift tents by hanging bedsheets from the top rack of their bunks to protect themselves from others’ coughing, sneezing, and breathing. ODRC said it was not aware of inmates making these tents.

On April 4, only one inmate had tested positive, but hundreds were already sick. Some inmates believe they contracted the virus as early as February, but the outbreak began to worsen in March and it really peaked in April, they said.

When about 30 National Guard medical team members arrived on April 13, the prison medical staff was totally overwhelmed, working 16 hour shifts seven days a week.

Inmates who were extremely sick, but breathing all right, were handed ibuprofen and cough drops and sent back to rest in their bunks.

Inmates banded together and cared for the sick in their bunk areas, doing whatever they could to help, like bringing back oranges from the “chow hall” to those who were not getting out of bed. One older inmate was confined to his bed for 12 days, Stufflebean said. On day six, staff took him to medical, but he didn’t need a hospital transport to get on a ventilator, so medical sent him right back.

Several inmates expressed concern about the lack of medical attention. One said the first thing he is doing when he is released is getting an X-ray on his lungs because he still feels a weight in the back of his lungs and is still having trouble breathing weeks after recovering.

Major Holly Hogsett, the Officer in Charge of the National Guard’s medical team at Pickaway, said their arrival allowed some relief for the “exhausted” prison medical staff. The National Guard assisted with some of the smaller tasks, like daily temperature checks of the entire prison and assistance in the nursing home, allowing the prison medical workers to focus on the more severely sick inmates.

Inmates were instructed to sleep head-to-toe, which only helps so much when everyone is that close. The prison had just begun shuffling inmates around when the National Guard arrived. Staff were trying to separate positives from negatives, but that was before inmates had been tested.

The prison added some bed space in various locations of the prison including a gymnasium. The National Guard set up tents outside.

On April 17, the entire prison population was tested. When the results were processed, prison officials decided that three of the four blocks – A1 and A2, B1 and B2, and D1 and D2 – would mostly hold positive inmates.

The two other blocks, C1 and C2, were for negative inmates. After the testing, there was mass shuffling of inmates.

“They shook up the whole prison. I mean, they should have just left everybody where they was at. Instead, they infected the whole prison,” said Jason Arnold, 40, of Muskingum County.

Anthony Triona, 27, of Licking County said there were five or six mass moves after the testing. He said the prison was “moving inmates in and out for no reason, spreading the virus.”

He said there was never any real way to practice social distancing.

“It was all a big joke. We are crammed in here like sardines, doomed from the beginning. One water fountain, sometimes only one computer to write our loved ones, we share everything,” Triona said. “We live too close to each other. The population is so above capacity.”

In many of the positive bays, the prison filled the aisles of the bays with extra beds to free up space in the negative bays, two inmates said. ODRC denied that beds were added to aisles.

The overwhelmed prison staff were frantically shuffling inmates around the prison, transferring people from positive bays to negative bays, or vice versa, inmates said. Arnold said he saw inmates being moved at 3 or 4 in the morning. ODRC said “bed moves were respectfully done during daylight hours.”

Tracy Fraley, 37, of Scioto County, was COVID-19 positive, but he was mistakenly placed in a negative bay, only to be moved out 24 hours later.

Chad Freitas, 51, of Warren County, on the other hand, was mistakenly placed in a positive bay because the staff thought he had refused to get tested. In fact, he was unable to get a test due to work duties. When staff learned that he had not been tested, he was pulled out to get swabbed. The result was negative, and he was removed from the positive bay.

A wheelchaired inmate, Buddy Joe Baier, 59, of Belmont tested negative. He was moved from B1, which has a handicap bay, to D2, a block with five positive bays and one negative bay. The negative bay’s occupancy has been reduced to around 20 inmates, some of whom are in wheelchairs like Baier.

The problem for Baier? He depends on being pushed by other inmates to move around. He said he is often pushed by positive inmates because it has been hard for the prison to get negative inmates down to D2 to push the wheelchaired inmates. Baier and others in his block say this puts them at significant risk of contracting the virus.

However, he is not necessarily mad about it. He actually wants to get sick.

“The positive people get to runaround, but we don't,” said Baier, who suffered a stroke and is paralyzed on his left side. “I hope I get sick so I can get the hell out of this damn place. You tell your readers that.”

Being in a negative bay in a positive block is like solitary confinement, he said. They get out for chow and a short recreation period, but other than that it is full lockdown. It is a struggle to even get to the ice machine, which is the only real way to cool down when it is 95 degrees and you cannot leave the un-airconditioned bay.

ODRC said that no known positive inmates were given the job as wheelchair pushers for negative offenders. In addition to Baier, Arnold also said positives were pushing negatives in wheelchairs in D2.

Earlier in the outbreak, inmates’ movement was most constricted if they were sick. Prior to testing, inmates said people were lying that they did not have symptoms because they knew if they admitted to having symptoms their movement would be restricted.

“Catching the virus here was more like a punishment then a treatment,” Fraley said. “No one wanted to report their symptoms because if so they locked you in isolation like you had done something wrong.”

Now, it is inmates like Baier who are most constrained.

The outbreak forced the prison to suspend school classes and other forms of programming available to inmates. Just recently classes have resumed. Inmates, who were previously approved to work outside the prison, mowing lawns and jobs of that nature, are no longer allowed to do so. It could be a risk to the surrounding communities.

Pickaway Public Health said prison staff cases have spilled out of the prison into the community, but more so into neighboring counties, where many Pickaway Correctional Institution staff reside, than in Pickaway proper. Michael Souders, who owns a lawn care company across the street from the prison, said much of the staff commutes from Columbus. Recreation time in the yard has been reduced from about nine or 10 hours per day to one hour before lunch and one hour after lunch.

With three fourths of the blocks designated for COVID-19 positive inmates, the prison, which relies on inmates for lots of essential labor, had to use positive inmates for jobs that should have been done by people who could not spread the virus.

Positive inmates worked in the kitchen preparing meals for the entire prison, two inmates said. Negative inmates took over the labor for a period of time, but for the last month, positive inmates have been back in the kitchen preparing food. ODRC denied that known positive COVID-19 individuals were preparing food.

Likewise, the prison had COVID-19 positive inmates work on decontamination teams that were responsible for spraying the prison with disinfectant, Smith said.

ODRC said any inmate on a decontamination team who was actively showing symptoms would have been removed from the assignment. A spokesperson also said the teams were wearing PPE.

Chief Lobbyist for the ACLU of Ohio Gary Daniels said Ohio prisons were about 10,000 people over capacity for many years, though the number has dropped slightly.

The union for Ohio prison staff says the state’s prisons have insufficient staffing to meet the large prison population. COVID-19 only made the matter worse, Ohio Civil Service Employees Association President Christopher Mabe said.

The ACLU has concerns across the board regarding the way COVID-19 has been addressed in the state’s prisons, including lack of proper sanitation and health precautions, inadequate or no social distancing even in areas where that could be accomplished, lack of protective gear, testing people and then sending them back to their cells before results are in, and not testing people who appear to have symptoms.

In terms of protective gear, inmates were given three or four homemade cloth masks in early-April when the virus was already out of control. Inmates described the masks as one-layer of t-shirt material.

Advocates and inmates say Ohio failed its most vulnerable inmates – the elderly and the immunocompromised – by choosing not to release at-risk prisoners en masse when the outbreak arrived in the state’s prisons, particularly those who are non-violent offenders, and then failing to keep them safe inside the prison.

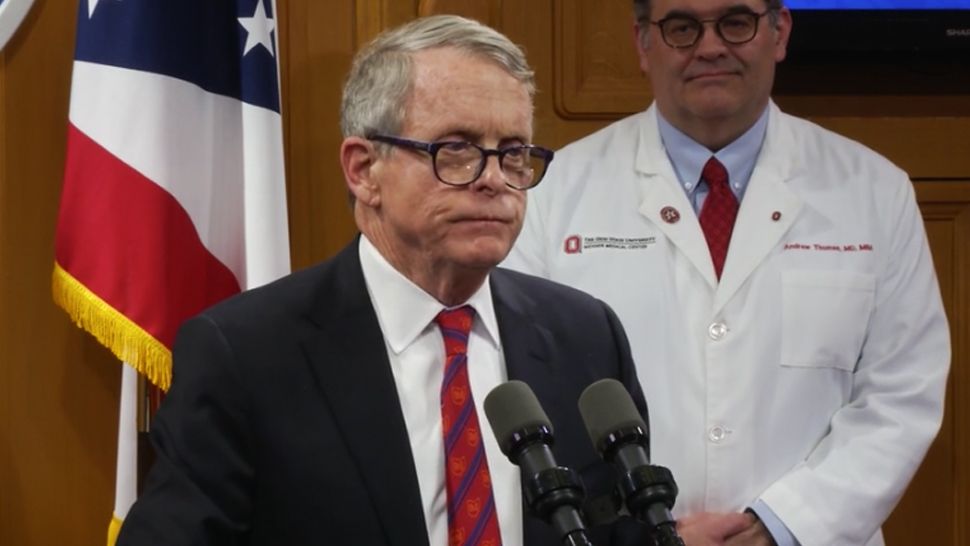

“The releases authorized by Gov. DeWine play a small part. He, the legislature, and judges could do much more but they refuse,” Daniels, of the ACLU, said.

Arnold said DeWine put so many stipulations to be eligible for release that basically none of his fellow inmates at Pickaway were eligible, not even non-violent offenders. Stufflebean said the stoppages of programming have shut off opportunities for inmates to earn good days, which can result in them being released a bit early. In effect, some inmates’ sentences have been lengthened rather than shortened due to the virus, he said.

Advocates and inmates say the Governor and the prison leadership are responsible for the 36 deaths and the mass suffering at Pickaway Correctional Institution. It could have largely been avoided, they say.

Souders, who owns the lawncare company across from the prison, said it was remarkable to watch the ambulances go back and forth.

One night, five inmates deteriorated at roughly the same time. Emergency responders formed a five ambulance “caravan” to transport the inmates to Ohio State’s Wexner medical center. That was late April, around the time when deaths peaked – seven inmates died in the three day period of April 27-29. Scioto Township Fire Chief Neil Cline said his department transported about 170 total inmates to Wexner, with other emergency response departments conducting an additional 30 ambulance transports.

Scioto Fire was running two ambulances “pretty much back to back” from the prison to Wexner for a couple weeks in April, but even that was not always enough. The other agencies filled in when more ambulances were needed. When critical inmates, still in shackles, were admitted to Wexner, many were immediately put on ventilators, he said.

About 20 inmates died at Wexner in Franklin County’s jurisdiction. Fifteen inmates died at the prison. Their deaths were processed in Pickaway County.

John Ellis, Pickaway County Coroner, said it’s a one-man operation there. Lots of weeks are slow. So the number of deaths that were coming out of the county during the prison outbreak was like nothing he had ever seen.

“I’ll go a week without a death, and then sometimes it’s three in one day. But 15 deaths in two weeks? Yeah, that’s a lot,” he said. “Our numbers were as high as New York’s if you count the prison.”

Most or all of the Pickaway County deaths were inmates receiving care from the prison’s Frazier Health Center, which is essentially a nursing home. Stufflebean said that several times on his way to the chow hall he saw squads taking out the dead in body bags – not the most appetizing sight before lunch, he said. A window near the chow hall looks out at the back of the nursing home.

The youngest Pickaway County death was a 58-year-old, the oldest was 87-year-old Arthur Jackson. The others were in their ‘60s and ‘70s.

ODRC declined to share the identities of 13 inmates who died, in cases where next of kin had not been notified as of July 9, which was almost two months after the last confirmed death date, May 22. Of the 17 inmates who died at Wexner who have been identified, the oldest was 90 years old and the youngest was 40-year-old Lawrence Miller II of Summit County, who was on a list for a kidney transplant and going through dialysis four or five times a day, according to his attorney, John William Greven.

“Lawrence was probably one of the most vulnerable of the vulnerable,” Greven said.

In a previous criminal case before the COVID-19 outbreak, Greven successfully secured Miller’s early release due to his health condition.

Then Miller was arrested again.

Due to his health, the victims of the crime did not want to see him go to prison. The judge still ruled to incarcerate him.

Greven said he had a meeting scheduled with Miller’s brother to discuss a legal course of action to get Miller released due to his health once the COVID-19 outbreak hit.

But before their meeting, Greven saw his client’s name in the obituaries section of a local paper.