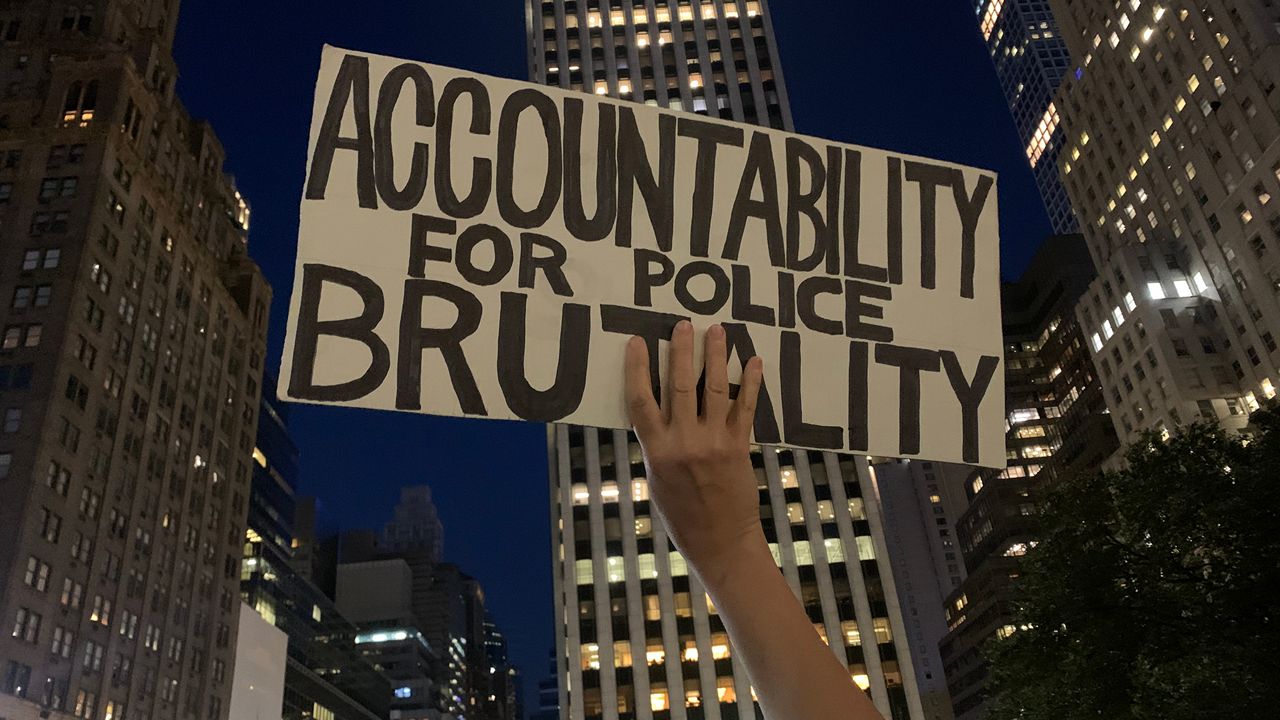

BOWLING GREEN, Ohio — During protests against police brutality in the summer of 2020, communities asked for accountability from law enforcement, sharing not just what happened, but also what consequences officers faced. Across Ohio, that desire extends to transparency around all possible crimes committed by officers, from petty misdemeanors to sex crimes and felonies.

In Bowling Green, professor and former police officer Phillip Stinson created The Henry A. Wallace Police Crime Database, the only one of its kind that documents and tracks police crime across the country.

Stinson said he has studied police crime since 2005.

Watch Part 1 of the special below:

It was only after beginning to aggregate this data that he said he began to realize the troubling and consistent patterns involving crimes by officers across the country.

When Stinson realized there’s no collection of data on police crime at the federal level, he began using Google Alerts with automated search terms to constantly search the Google News search engine.

“We find between 1,100-1,200 instances each year consistently where officers get arrested across the country,” Stinson said.

He now has a staff of about a dozen student research assistants during the academic year. They log each case in the Henry A. Wallace Police Crime Database.

The database categorizes crimes committed by law enforcement, bringing light to the patterns of police misconduct. Stinson said his research shows most police crime is alcohol related, drug related, sex related, violence related and/or profit motivated.

“In the last few years, I’ve been thinking there’s really a sixth type: It’s motivated by revenge, that it’s really for the sport of messing with somebody,” he said.

Watch Part 2 of the special below:

Stinson and his team have completed coding 11 years of data. It totals about 12,000 cases of crimes committed by a little under 10,000 officers. The public can search the database by location, crime and/or by the victim.

Stinson’s work comes with occasional criticism from former police officers. But he sees his work as just the opposite.

“The purpose of my work is to improve policing, to look at this data, to figure out how can we study this data, what sort of statistical analysis can we do quantitatively so that we can identify problems and then try to figure out ways to address them,” he said.

In Cleveland, a court-ordered consent-decree requires the Division of Police to implement recommendations from a Civilian Review Board to increase accountability and transparency. Jason Goodrick, executive director of the Cleveland Police Commission, worked to pass legislation last November that ensured the continuance of citizen review.

Goodrick said there’s more than a police misconduct issue, there’s also prosecutorial misconduct problem.

“They [prosecutors] will receive a case, it has a police officer involved in the case, and for whatever reason they decide to decline a prosecution of that, whereas civilians are often prosecuted," he said. "I think the community sees that, that there’s a great disparity, and that’s where a lot of the trust issues come from."

Stinson said the Henry A. Wallace Police Crime Database works to increase transparency and inform the public.

“In most places, there’s no legal requirement that they [police departments] disclose [misconduct] to the public, sometimes they don’t even have to disclose to the state, and they certainly don’t have to disclose to the federal government,” said Stinson.

Cincinnati’s outgoing Police Chief Eliot Isaac said he supports establishing a national department to prevent officers from committing a crime, leaving their department, and beginning over at a new department. The Cincinnati Police Department has early intervention systems in place to help catch police misconduct in its infancy.

Watch Part 3 of the special below:

“My command staff and I meet quarterly to address any officers that are outliers in their peer groups and to determine any necessary action to address their performance, perhaps their use of force, their citizen complaints and alike,” Isaac said in an interview conducted in 2021.

Amid calls for police reform and transparency are also demands to defund the police.

“We’ve seen across this country that some policies need to change. We see that more community involvement and engagement must happen, and so when people say ‘defunding,' I just change that to ‘OK, so you want reform,'" said Assistant Chief of Police in Columbus LaShanna Potts.

Across Ohio, there have been attempts at reform.

In 2001, an unarmed Black man named Timothy Thomas was shot by Cincinnati police. In response, a Collaborative Agreement, imposed by the Department of Justice following an investigation, prioritized new measures of accountability and the hiring of minority officers. Isaac said as a result, they’ve made two decades of reform and he believes they are now a department that embraces change. He said they’ve focused on three pillars of reform.

“Changes to our use of force polices, changes to how we would have greater transparency and accountability, and then the third piece, really working toward bias-free policing and community problem solving,” Isaac said.

In Columbus, the Civilian Police Review Board works to restore trust between the community and police. It focuses on accountability and transparency.

Watch Part 4 of the special below:

“The chief and I want that," Potts said. "We want those eyes and ears”.

In November 2021, voters in Cleveland overwhelmingly passed Issue 24, continuing the work of the Citizen Review Board to oversee police conduct established by the Consent Decree of 2015. This inserts the commission between the city safety director and the mayor. So the chief and safety director will now have someone to report to.

Regardless of the calls for reform, Goodrick believes communities should have hope. He doesn’t expect that anyone demanding reform will let up off the gas.

“So they [police] need to grow and learn how to be in the environment of constant oversight," Goodrick said. "Then, they need to hold themselves to higher accountability internally.”

He said that’s the only way trust will be restored.