The county’s goal is to open much of that shoreline by forming partnerships with hundreds of property owners — from single families and property associations to special interest groups and descendants of early industrialists who’ve owned properties for decades.

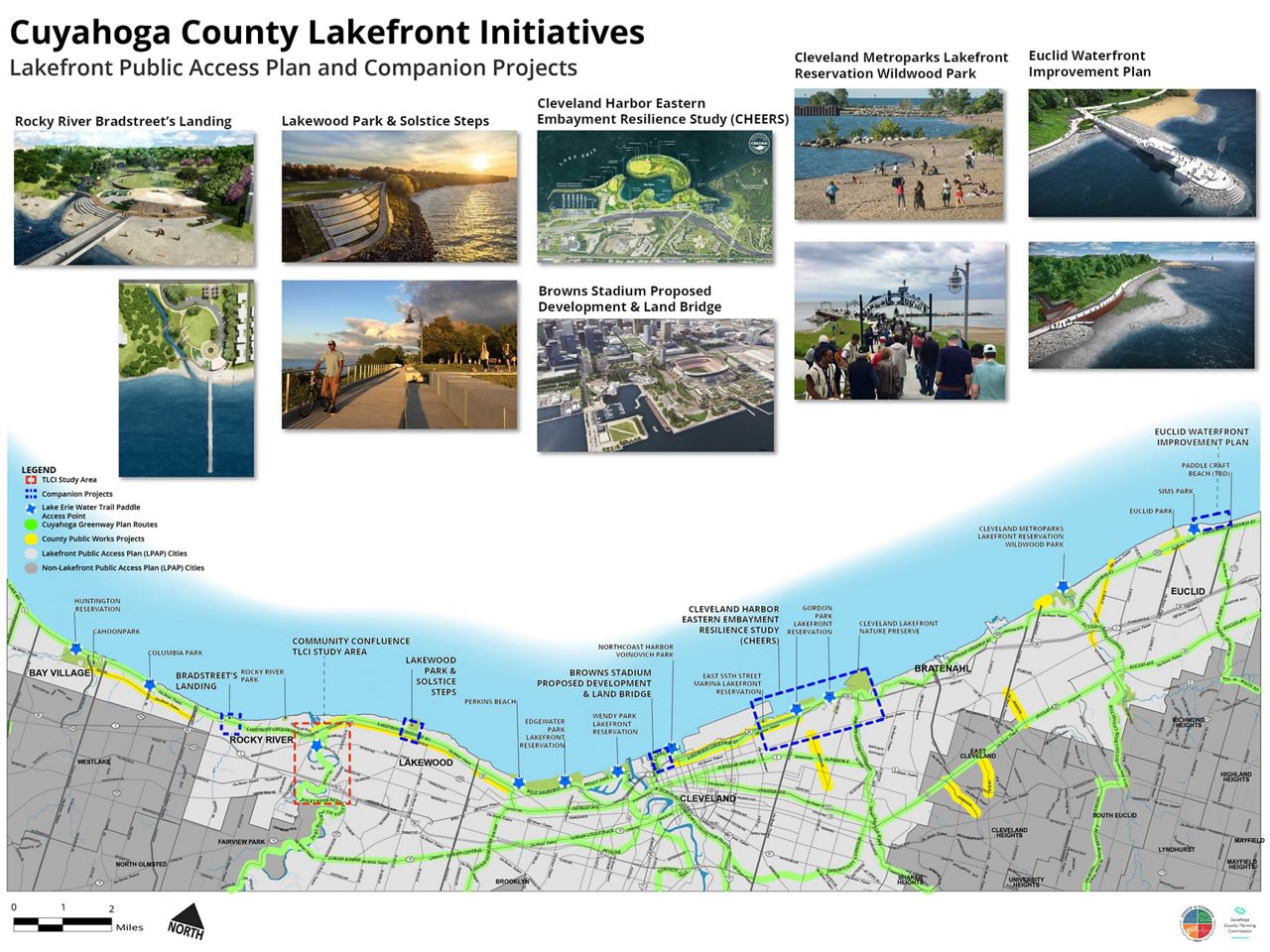

The groundwork for the Cuyahoga County Lakefront Public Access Plan was laid in 2019 when County Executive Armond Budish took a close look at the Euclid Lakefront Development Plan, a multi-phase initiative to revitalize and open that city’s waterfront through a public-private partnership.

Budish asked his public works department if such a thing were possible in the rest of the county, said Public Works Director Michael Dever.

“He felt like if there was an important project or priority here in the county it should be trying to gain access to our waterfront,” he said.

Working with a consulting team led by SmithGroup, an integrated design firm, the Public Works Department and Planning Commission picked up the gauntlet and began talks with a series of key agencies, including the Northeast Ohio Areawide Coordinating Agency (NOACA), the Northeast Ohio Regional Sewer District, Cleveland Metroparks, and the municipalities involved.

“We did a lot of legwork upfront, just to make sure that we had all the right stakeholders on board and a lot of active interest, and people who really wanted to contribute to making this an equitable, publicly accessible lakefront,” said Jim Sonnhalter, Planning Commission manager, design & implementation.

The goals set for the Cuyahoga County Lakefront Public Access Plan:

- Create a connected network of access points;

- Position the lake as an asset;

- Address erosion and protect private property; and

- Make the lake a healthier, safer place.

The coverage area is ambitious, extending from the shoreline at the Lake County border on the east to Lorain County to the west, which represents very different types of terrain. The plan includes six jurisdictions, within which planners have started working on strategic, bite-sized sections, usually in conjunction with other agencies.

“My thought is that there's a series of projects going on, and we're really here to complement each of those projects,” Dever said. “It's linking them together, ultimately, is what we're trying to accomplish. We're not going to touch the water on every one of those 32 miles, but linking in each of those individual projects.”

Planners have asked for input from property holders and residents along the way, with the next virtual public information meeting set for 6-7:30 p.m. on Tuesday, July 13. The meeting is accessible through a website dedicated to the plan.

All that coordination is necessary to ensure the plan dovetails well with the existing initiatives the plan overlaps. Among them are the Cuyahoga Greenways Plan, which is building a network of trails linking communities in the northern-most portion of the state with Lake Erie and the Cuyahoga River, and NOACA’s Regional Lakefront Transportation for Livable Communities study, which seeks to strengthen multi-modal access to the lakefront for all Ohio’s lakefront counties.

“We don't want to stand still, and just play something out, and then try and figure out what the next steps are,” Dever said. “We're trying to actually move into an implementation phase on a few of these projects so people can see, you know, what are you doing besides just talking about it?”

In earlier public meetings for lakefront public access, property owners have been keenly interested in what such a project would look like, who would be responsible for what aspects of the plan and how public versus private interest would be balanced, such as privacy, safety and hours of operation.

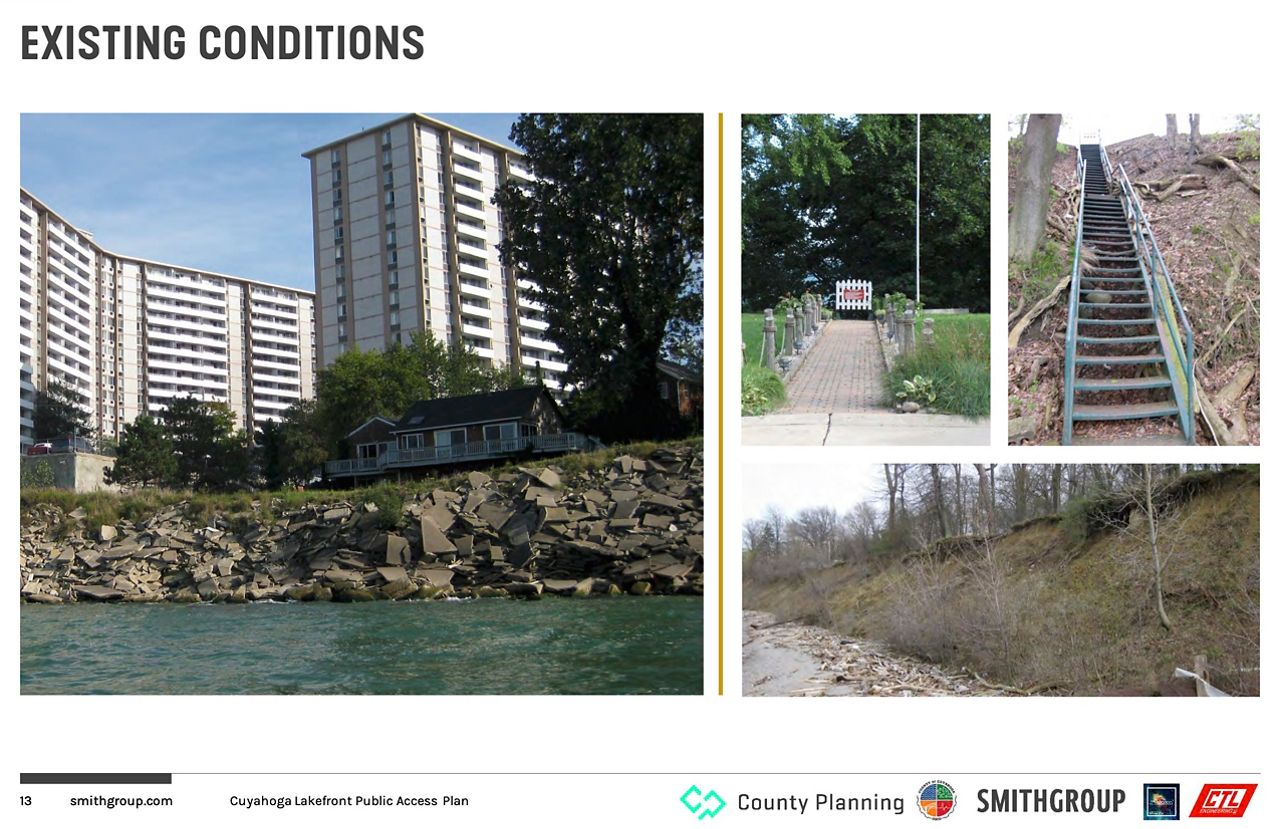

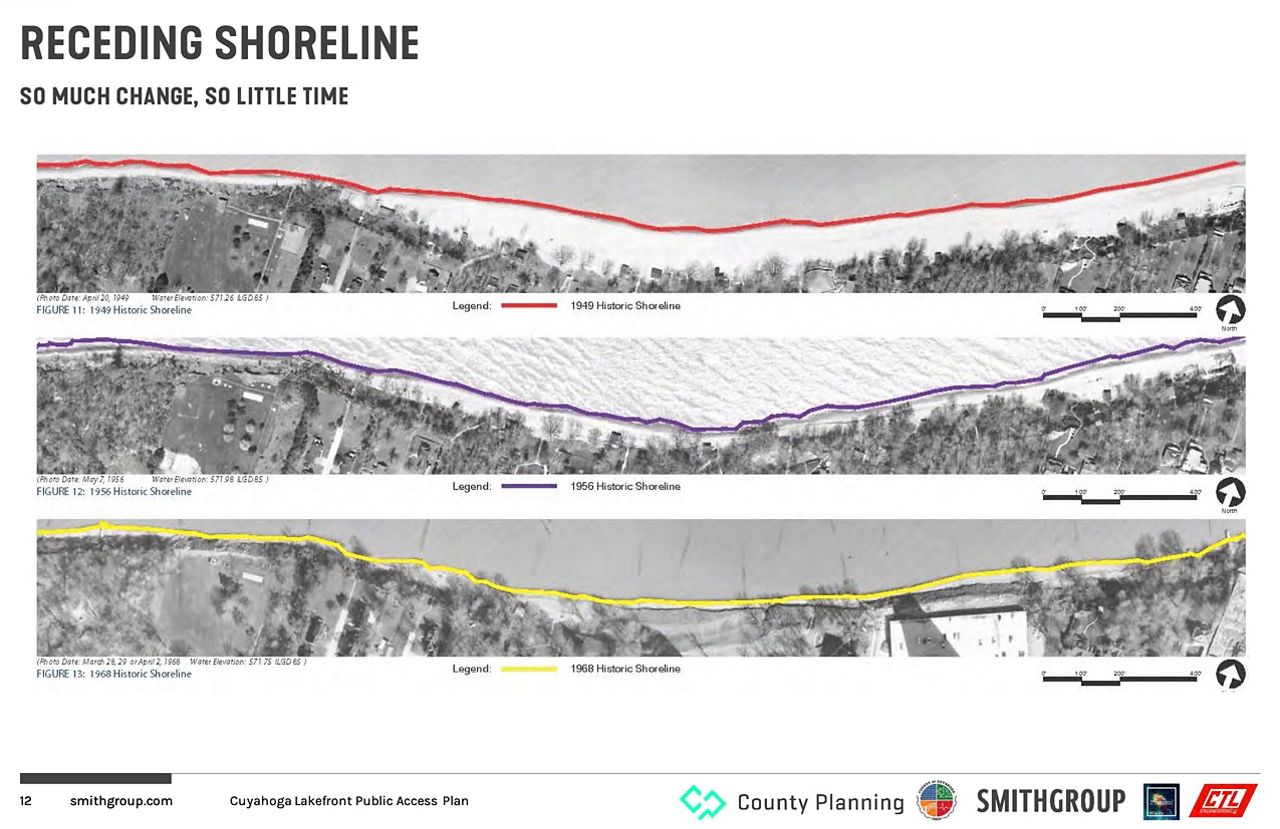

But among the most critical aspects of the plan to property owners is concern over the erosion of the Great Lakes’ shoreline.

A recent property-owner survey the county conducted revealed more than 70% of respondents said they would lose land from erosion, and 25% would lose some kind of structure.

“The lake certainly doesn't recognize property lines,” Sonnhalter said. “And your neighbor to the west may have put up some sort of erosion control structure, but that's not necessarily helping you.”

Nearly 70% of respondents said they had not yet looked into the necessary permits to install erosion control.

Erosion control is not only expensive, it’s regulated by the state, the EPA, the Army Corps of Engineers and other agencies.

Cost estimates for work range from $3,500 to nearly $7,000 a linear foot, Dever said.

The plan is presented as a solution in which both sides can benefit, as the county is more likely to have access to erosion-control funds than private property owners, said Planning Commission Executive Director Mary Cierebiej.

“It's been really a dialogue. This is not a ‘taking,’” she said. “This is really about a partnership and how do we help not only the people who live along the lake and have access to it, but those who don't have opportunity to access the lakefront?”

And the plan includes more than shoreline improvements, she said. It’s enhancing and networking bike and pedestrian lanes along the north/south corridors as well.

When asked in the survey whether property owners would allow a public trail on their property as part of an erosion-control project, nearly 29% or respondents said yes, while 40% said they need more information.

That information has been forthcoming because the bottom line for the project’s success is buy-in from the property owners.

“They want us to help them with erosion-control efforts, we need to have public access, and we're being quite candid about it,” Dever said. “We're not trying to hide anything here. But there's a give and a take.”

Some areas along the lakefront require critical improvements that are a necessity, more than recreation, Cierebiej said.

One such project is underway at Beulah Park in the Collinwood neighborhood. The county has applied for emergency funding for erosion control through the Ohio Department of Natural Resources, she said. The Northeast Ohio sewer district also has made a significant investment there in sewer outfalls.

“It's vitally important to try and stabilize that shoreline because it's one of those things, if nothing is done on the adjacent properties, they're going to have a risk to their large investments, and they're being damaged,” she said.

At the same, the county is looking at the roadways leading to about a one-third mile of waterfront at Beulah Park to determine whether the area can be made more accessible to the public, Sonnhalter said.

“So we think this is an exciting project right now, and one that we're using as one of our focal points on the east side,” Sonnhalter said.

Making it easier to present the county’s plan is the success of the Euclid Lakefront Development Plan, Dever said.

A few years ago, the city of Euclid also enlisted SmithGroup to help develop a multi-phase waterfront project revitalizing a three-quarter mile stretch of the city’s four-mile waterfront. The project was first envisioned in 2009.

“It took a good two years of talks and just absolute transparency with the property owners to really develop what became a public-private partnership,” said Sonnhalter, who previously served as planning and urban design manager for Euclid. “So in exchange for shoreline protection, the private property owners granted an easement and that was what allowed the broader project to go forward.”

Euclid’s Phase 1, completed in 2020, featured the construction of a new pier at Sims park, expanding fishing access and improving a series of trails. Phase 2 includes the creation of public pathways and boardwalks, incorporating shoreline protection as well as habitat and recreational enhancements. Phase 3 is expected to include a public marina and trails connecting to existing neighborhoods.

“We're so fortunate to have the Euclid model, as something that people can look at, touch and see, and how it impacts those private property owners,” Dever said. “So that has been such a great example. And we'd love to be able to replicate that over on the west side.”

The Euclid project represents a winning combination, Cierebiej said. It’s a city that wants more lakefront access for residents and property owners are in agreement.

“That's really what we're striving for,” she said. “I think the goal for us coming out of this planning is here's the focus areas that we'd like to see move forward based on the input from the property owners and the public. Here's what the next projects are and then how do you take those and apply for funding, much like we were doing at Beulah Park this year? Which ones are in future years, andapply for the same kind of funding?”