LOUISVILLE, Ky. — Janet Heston never had reason to give much thought to the tens of thousands of people killed on America’s roads each year. Then, it happened to someone she loved.

In 2019, a driver hit Heston’s son, Matthew, as he was crossing New Cut Road in South Louisville. Then, another driver hit him.

“His body was so badly damaged that they had to do fingerprinting,” Heston said. “That’s when everything changed. This has become my mission.”

In the time since her son’s death, Heston has become an advocate for the Vision Zero initiative, which encourages communities to work toward a goal of eliminating all roadway deaths. Now, Louisville has joined the movement.

On Thursday, Metro Council passed an ordinance adopting the Vision Zero framework, setting a goal of zero traffic fatalities by 2050.

“In Metro, one person is killed every three days in a roadway injury,” said Council Member Nicole George, D-21, lead sponsor of the ordinance. “Fatalities are preventable and roadways can be designed to anticipate human error.”

George said the city’s Public Works Department is already engaged in the work that Vision Zero encourages, but by formally adopting the policy last week Louisville has made itself eligible for millions in federal funding.

“We are already doing this work. We are at the forefront of the work,” Amanda Deatherage, Transportation Planner Supervisor for Louisville Metro Public Works, said at a Metro Council meeting this month. “We need to formalize this commitment so that we can take advantage of every opportunity to save lives.”

And there are a lot of lives to save on Louisville’s roads. The city is currently on pace to see 132 people killed on roadways this year, according to the city’s “crash dashboard.” That total would be surpassed only by the 140 killed in 2020. Motor vehicles deaths are the leading cause of roadway fatalities, accounting for more than half each year. Pedestrian deaths are typically next, followed by motorcycle and bicycle deaths.

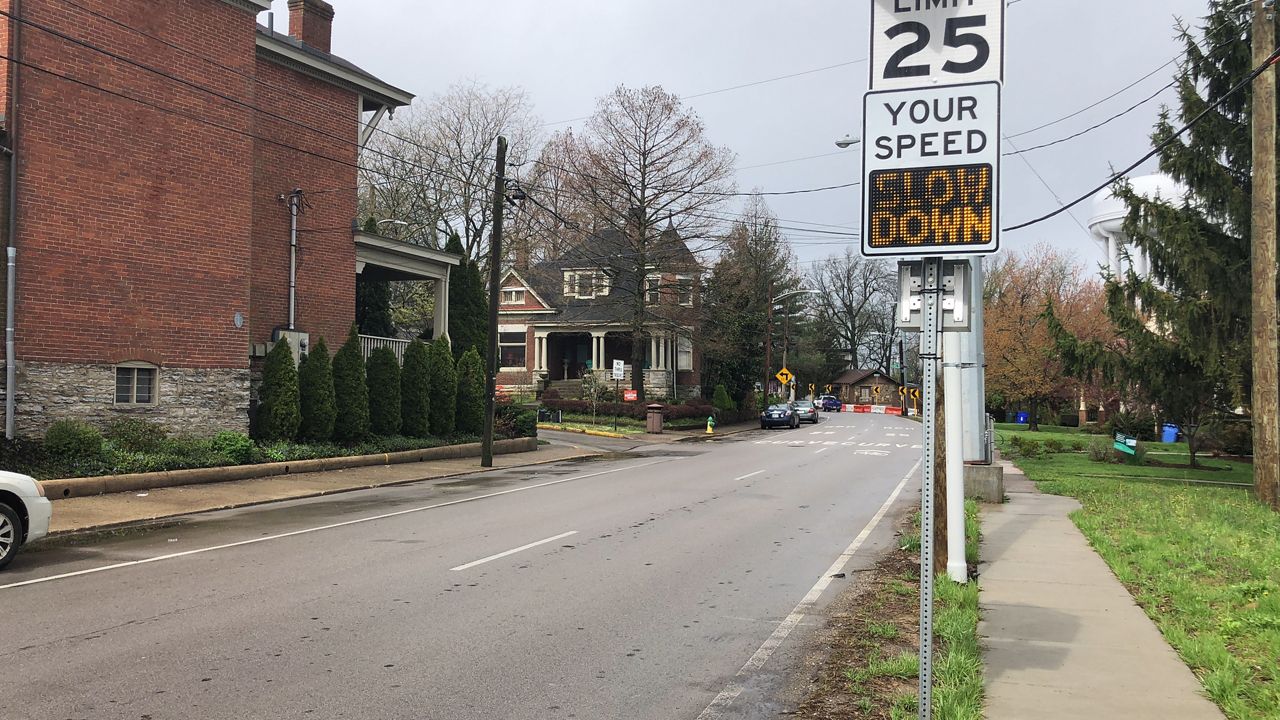

Heston doesn’t like to call these crashes accidents. “For the most part, crashes happen because people are speeding, people are distracted, or people are not staying within their boundaries,” she said. Heston believes that traffic calming measures that reduce speed and force drivers to pay more attention can end these tragedies.

The stretch of road where Heston’s son was killed provides an example of an area that wasn’t designed with safety in mind, she said. Matthew was killed while crossing the street to a mid-block bus stop, which she said shouldn’t exist. “You make sure bus stops are places where the bus itself and people getting on and off are going to be highly visible,” she said.

“If you go out there to where my son was killed, it goes from a pretty congested area to an area where lanes are as wide as 13 feet,” she said. “You have four lanes in either direction and no median as a safe haven.”

That type or road design can lead to speeding, according to a 2021 report from the Johns Hopkins Center for Injury Research and Policy. The report encourages the adoption of a “safe system” road design, which includes measures such as replacing four-lane roads with two-lane roads that include a center turn lane, and the adoption of more roundabouts, center medians, rumble strips and lighting.

The report cites major progress in reducing fatalities in cities and countries that have adopted a “safe system” approach, including Mexico City, which saw fatalities fall by 18% between 2015 and 2018, and Spain, which saw an 80% reduction in fatalities between 1990 and 2017.

There’s already evidence this approach can work in Louisville. Over the past decade, the $35 million New Dixie Highway Project transformed one of the most dangerous stretches of road in the city. The project involved building medians and left hand-only turn lanes, among other design improvements. It’s had a dramatic effect, reducing crashes from an average of 1,067 crashes per year to only 154, according to a presentation Deatherage gave to Metro Council.

With the broader implementation of safety measures like those, and the increasing availability of car safety technology, Heston believes the goal of eliminating roadway deaths is within reach. “These things are tried and true — they’re science,” she said. “And it’s absolutely achievable.”