CRESTWOOD, Ky. — There’s an app on Lottie Tanner’s phone counting the seconds since she last saw her husband, an inmate at Kentucky State Reformatory (KSR), without a sheet of plexiglass between them.

“Our last contact visit was two years, 46 days, 13 hours, and nine minutes ago,” she said Saturday.

This week, Lottie and Michael Tanner will see each other in-person for the first time since prison visitation was suspended in January because of the surging omicron variant. But it’s a no-contact visit, so the app will keep counting.

“At this point, I’d settle for a hug,” Tanner said.

Several states that suspended prison visitation this winter opened back up in February or March as omicron faded, but Kentucky has still not reopened all of its prison facilities. Instead, the Department of Corrections (DOC) has staggered reopenings, with several facilities allowing visitors in March, others reopening this month, and the rest scheduled to do so by May 10.

This process has caused Tanner endless frustration, especially with COVID cases in Kentucky prisons at zero as of April 1, according to the DOC’s own numbers.

“We should have had visits back for at least a couple months,” she said.

That would have been in line with Louisiana, which suspended prison visitation in early January because of omicron, but ended that suspension in late March. In its announcement on the resumption of visitation, the Louisiana Department of Public Safety and Corrections said, “Maintaining in person connections with loved ones is critical to a person’s success in prison.” Colorado also allowed visitors back to prisons in March.

Wisconsin allowed visitors back to prisons on March 1, even with 77 active COVID infections. “Family connection during incarceration has shown to have a positive impact on success upon return to the community, and in-person visitation is one way of maintaining that connection,” Kevin Carr, the state’s DOC Secretary, said in a press release.

Tanner said Kentucky inmates have been deprived of this connection for too long. Her concern is especially high for children, who won’t be allowed to visit even once the current suspension lifts. Visitors must be 18 or older, according to the DOC.

“If you can’t bring kids that are unvaccinated, I understand that,” she said. “But six and up should be able to come to visit and they’re not allowing that. That’s been my biggest complaint with the governor. He’s very pro-family, but our families count too.”

Kentucky’s DOC made visitation decisions to “save as many lives as possible from the public health crisis of COVID-19,” spokesperson Kathrine Williams said in an email. They set guidelines “to keep staff, inmates and visitors healthy while inside a congregate setting” and to protect the communities in which the prisons are located, she said.

“DOC is continuing to monitor COVID outbreaks and plans to make adjustments to the visitation guidelines in the near future,” Williams wrote.

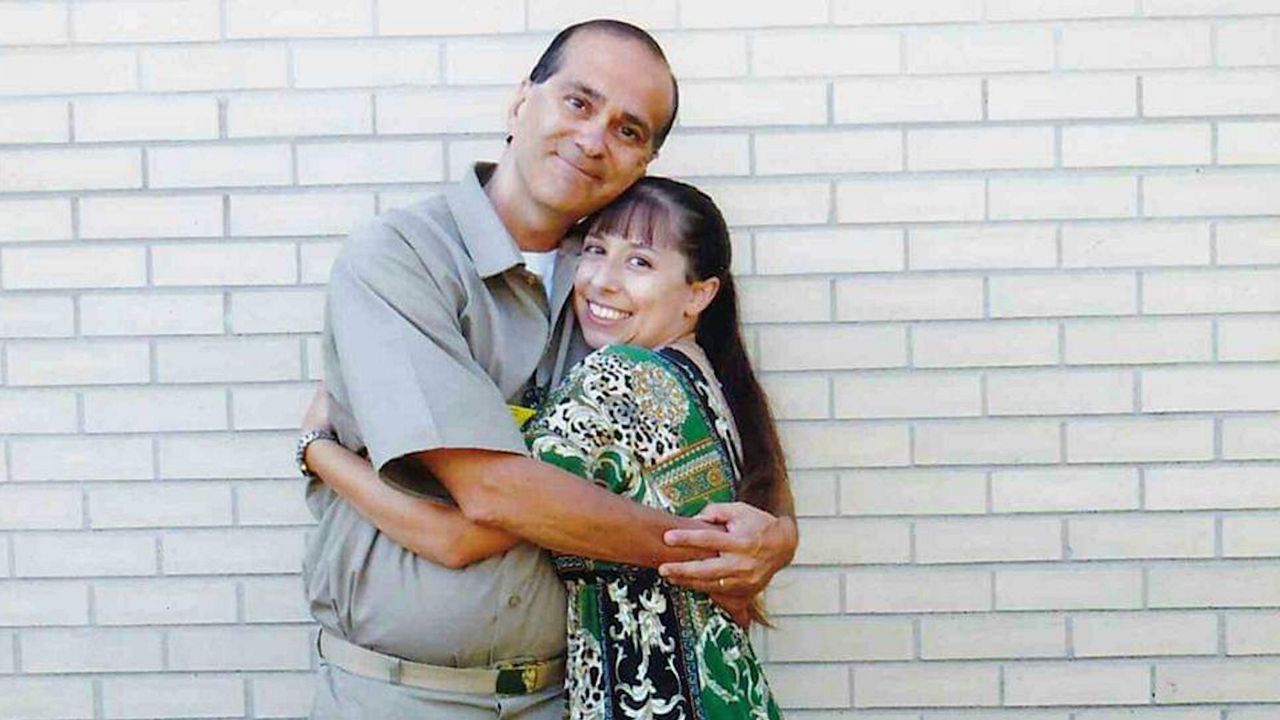

In some ways, Tanner owes her marriage to the German filmmaker Werner Herzog. His 2011 death row documentary, Into the Abyss, radicalized the New Jersey native, turning her into a vocal death penalty abolitionist.

Before long, she was spending untold hours writing to death row inmates. “I was like, ‘I can’t abolish the death penalty by myself, but let me make one person’s life better,’” she said.

In the summer of 2015, when a friend suggested she write to the man who would later become her husband, Tanner almost declined. “I had 17 pen pals at the time,” she said.

But she couldn’t help herself and added an 18th. “That was July of 2015,” Tanner said. “By September of 2015 I had come to visit him. By October 2015 we were engaged and I had moved here.”

They were married the next summer, and for three and half years, they settled into a routine. For a time, Tanner could visit KSR for six hours at a time. Then the rules changed and she was allowed two-hour visits on both Saturday and Sunday. During visits, the couple played games, and Lottie would buy snacks for Michael from the vending machines. “I tell people, we’re a really normal married couple,” she said.

All that changed in March 2020, when the DOC suspended prison visits at the start of the pandemic. Those rules were held for over a year. In the summer of 2021, KSR opened up again to visitors.

“In such a weird way, when I went back there for the first time, it felt like home,” Tanner said. “That was both scary and comforting.”

When visitation was suspended again in January, Tanner said she figured it would be temporary. Instead, it has dragged on for nearly five months. Now that it’s resuming though, contact is still prohibited, which Tanner said doesn’t make sense.

“Now that we’re vaccinated and boosted and I don’t see a mask in sight, I don’t understand why we can’t have contact visits back,” she said. Williams, with the DOC, did not respond to a question about this policy.

Despite the limitations, Tanner is excited to see her husband Wednesday. She remains frustrated at the slow pace of reopening, especially as the world outside of prisons resembles pre-COVID times and she has her theories for what that’s happening.

“I think it’s disregard for incarcerated people in general,” she said.