LEXINGTON, Ky. — Small, privately owned farms are disappearing. A recent study by the Union of Concerned Scientists shows the trend has changed the landscape of rural America, not necessarily for the better.

What You Need To Know

- Nearly half of midsize farms in the Midwest have disappeared since 1978

- Around 700,000 farms have disappeared nationwide

- Black-owned farms are decreasing as well

- Kentucky is one of the 16 states that collectively account for 95% of the nation's Black farmers

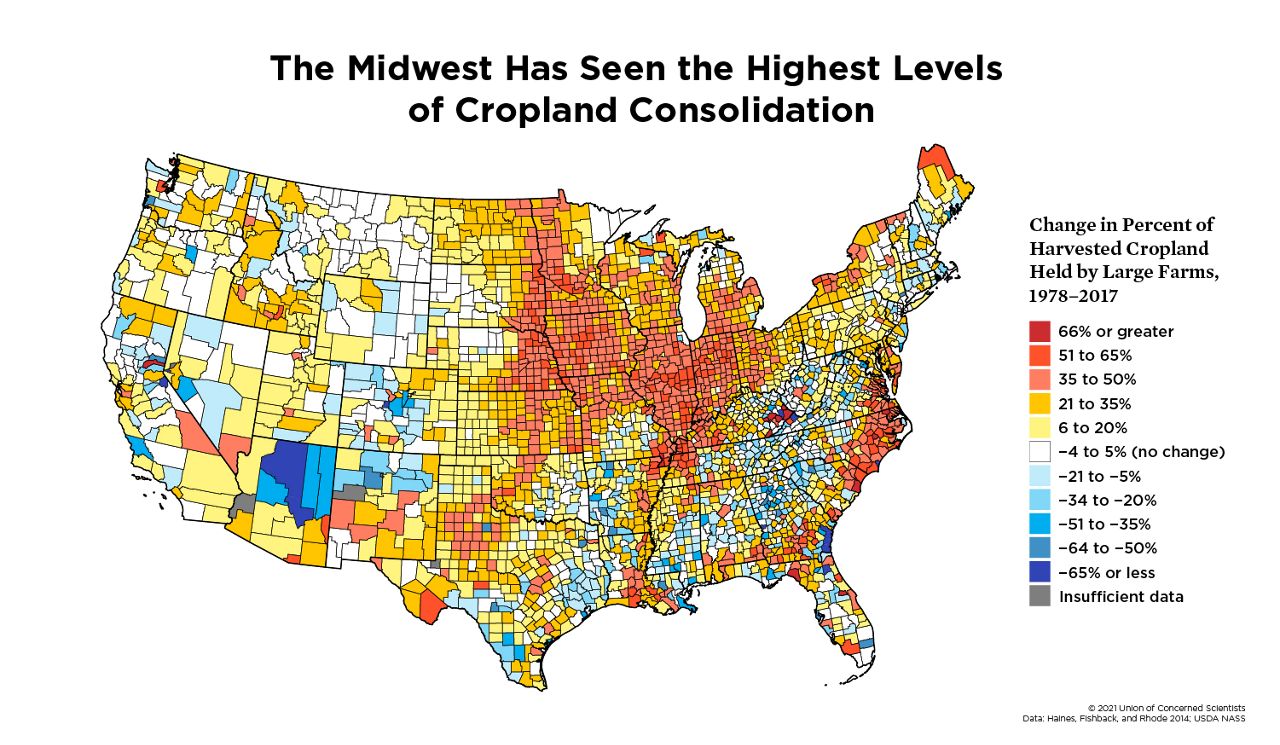

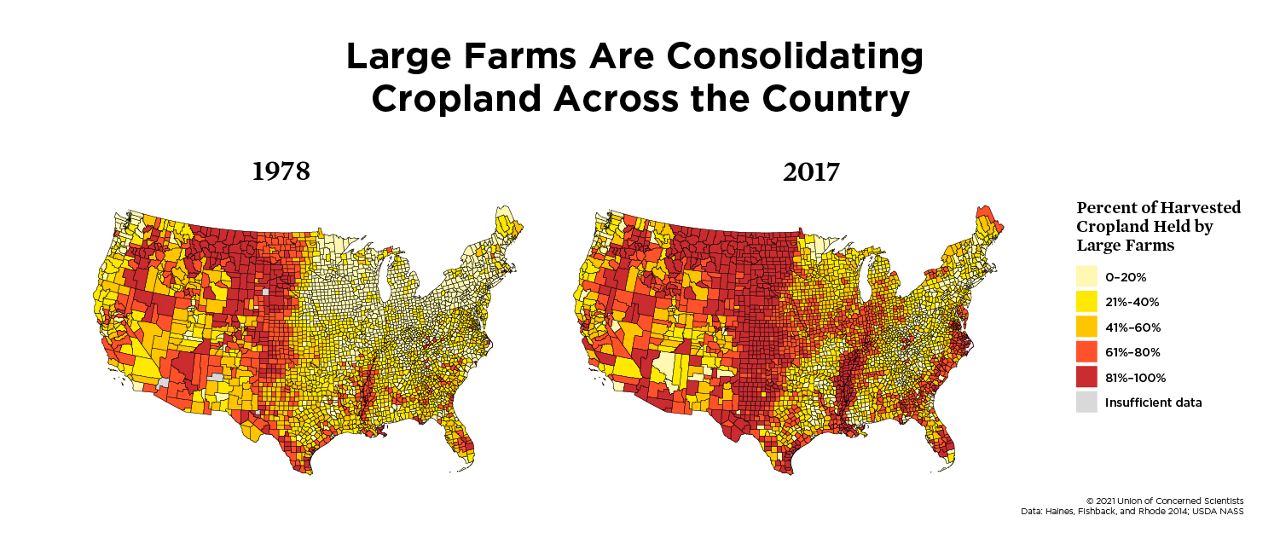

The number of farms is shrinking along with the population in rural America. Researchers studied farm consolidation trends between 1978 and 2017. They concluded that rural communities are at risk. Half of the Midwest's midsize farms have disappeared in nearly four decades – nationally, nearly 700,000 – while large farms have increased in scale by about 100 million acres in the same timeframe. According to the study, a midsize farm is between 50 and 999 acres, while a large farm is 1,000 acres or more.

Those midsize farms are historically the "backbone of the rural economy,” said study author Rafter Ferguson.

Consolidation happens when large farms acquire land that formerly belonged to smaller ones. Government policies that have consistently favored larger farms—along with the competitive advantage granted by economies of scale—made consolidation into a pervasive trend across the country for nearly a century. Over time, this has meant a shrinking number of farm operations, as more land is taken up by a small number of larger and larger farms.

Larger farms are not a problem in and of themselves, but their proliferation makes it harder for smaller, beginning farmers to compete and be profitable. The study shows: "The energy, innovation, and initiative that new practitioners bring are crucial to the future of any profession – and farmers are no different. Our food system will be facing huge challenges over the coming decades, and we need an expanding, diversifying, creative community of farmers to meet those challenges. Consolidation operates in exactly the wrong direction."

The study also sees environmental impacts: "Because more farmland in larger farms tends to be rented rather than owned, there is less incentive to invest in measures to improve farmland for the long term by building soil health. In short, when farms grow bigger and farmers grow fewer, bad things happen."

In Kentucky, small farms are not only disappearing but so are Black farmers. Kentucky is one of the 16 states that collectively account for 95% of the nation's Black farmers, along with Texas, Mississippi, Alabama, Louisiana, Georgia, South Carolina, Florida, North Carolina, Virginia, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Tennessee, California, Michigan and Maryland. The number of Black farmers in Kentucky declined from 928 in 1978 to 385 in 2017. Meanwhile, over the same period, the share of the state’s farmland held in farms of 1,000 acres or larger increased from 7.3% to 26.9%.

There are multiple reasons why increasing consolidation is concerning, according to the study. For one thing, larger farms mean that fewer people can be farmers. Consolidation operates to make farming a more exclusive club – and this has the most significant impact on groups that are already underrepresented.

The study focused on how consolidation may be driving exclusion from farming for two populations: New farmers, focusing on the Midwest, and Black farmers, focusing on the 16 states with the most significant number of Black farmers in 2017.

Jim Coleman, 60, who is Black, owns Coleman Crest Farm in Lexington’s Utteringtown Community. His great-grandfather and former slave, James Coleman, purchased the land that became Coleman Crest Farm in 1888 for $1,200. The farm was passed down through family members until Jim and his wife, the late Cathy, bought the farm in 2001.

Jim Coleman is a retired marketing, sales and economic development executive who graduated from Howard University and worked in New York, Maryland and other places for 42 years before returning to the farm he grew up on after retiring. He said he knows better than most about farm consolidation in rural communities, small farm owners, and Black farm owners in Kentucky.

“It's crowding out the younger people that want to get into farming,” he said. “There is already a tough barrier to get into farming, and with these big consolidations, it just makes it even more difficult. The scary thing is that the average age of farms out there is 58 years old and where we get the majority of our really clean, organic natural produce is from local farmers. They’re pushed out. There’s going to be less of an opportunity for health-conscious consumers to be able to get access to naturally grown organic crops.”

Coleman said the opportunity to own land and access fresh, natural produce is threatened through farmland consolidation. The “big guy” companies buy the land to use it for testing and growing food to sell directly to the large grocers and other businesses.

“They're taking over the entire food chain by doing that,” he said. “Any of the companies out there producing the science-related (crops) or chemicals, they're the ones that are putting up a lot of money to buy farms and consolidate them, so they've got a better distribution of their products and services.”

Coleman said what most farms need more than anything is a grant, but not the financial kind.

During a celebration at Coleman Crest this past September, he received a call from Gail Walles, Lexington, who had been organic farming for the past 15 years and was close to retirement. “They told me they would like to share ideas with me on how to make sure I’m successful,” Coleman said. “They invited me to come down to their home and their farm, and they gave me a tour and showed me all the things they're doing. Through that conversation and over the next couple of weeks, they introduced me to about four of their customers, which helps a lot because now I'm not growing on a speculative level. I’m growing to satisfy the real demand of customers who are looking for a natural product. On top of it, they have a son named Grant, a second-year sophomore at the University of Kentucky studying agriculture. He used to help them on their farm. But since they're winding down, she said you don't have to hire him, but if you're interested in talking to him, he could probably help you. I talked to him, and I hired him. That's the kind of grant small farmers need.”

Keeping small farms open and operating in the Lexington area is one of Coleman’s main goals, and doing so is not entirely dependent on financial grants or subsidies.

“What we really need is what I just shared,” he said. “We need customers. We need to know how to grow the right product that will cater to a consumer out there willing to pay the right price, which is a premium price, to make your farm productive and profitable. You need advice, and you need farm managers from the University of Kentucky or wherever – you need some expertise and a farm manager to help you to get rolling until you can really get this thing down.”

Coleman is adamant about encouraging young people to consider a future in farming. He has started an incubator program for aspiring farmers to gain experience.

“If they can get the experience, the know-how, and the planning and the business side of how to even get a good customer, and how to keep and satisfy that customer, then when they go to a bank to borrow money to buy a five or 10-acre plot of land or more, they've got the credibility, they've got customers, and they've got the operating experience,” he said. “That's what millennials who want to get into farming don't have. They've got too much debt from going to college, so they can't figure out how to handle that debt and take on more debt. They don't have the operational experience of how to manage a farm.”

According to the study, everyone is affected by the economic, social and environmental well-being of farming communities.

“Reversing the trend toward farm consolidation is a crucial step toward building a healthier, more equitable, more resilient food system,” according to the study.