LEXINGTON, Ky. — In addition to the many local, state, and federal offices on the ballot for the Nov. 3 General Election, voters in Kentucky will also be deciding whether to adopt a pair of amendments to the state constitution.

What You Need To Know

- Amendment 1, Marsy's Law, adopted in 2018 but overturned by Kentucky Supreme Court

- Amendment 2 changes term limits, qualifications for some judges

- Both measures appear in full on ballot

- Kentuckv ACLU opposes Marsy's Law, claiming it infringes on due process

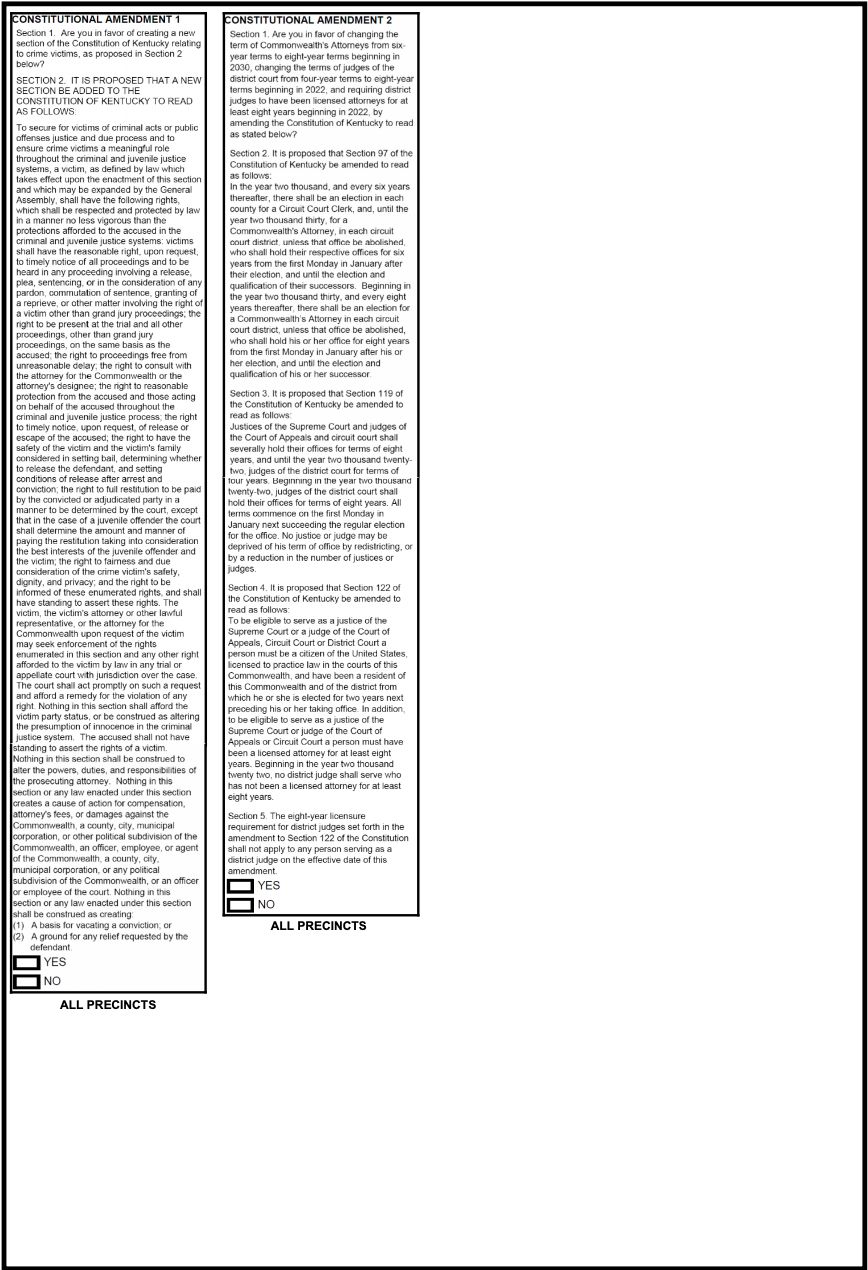

On the back of one-page ballots and at or near the end of multi-page ballots is Amendment 1, which establishes a section to the Kentucky Constitution related to crime victims, also known as Marsy’s Law, and Amendment 2 changes the way voters elect some state court officials.

Kentucky is one of only 15 states that does not provide crime victims with constitutional-level protections, and Marsy’s Law may seem familiar to voters across the Commonwealth. The law was adopted in 2018 and garnered nearly 871,000 (63 percent) “yes” votes but was overturned in 2019 when the Kentucky Supreme Court ruled unanimously the amendment’s wording was too vague.

“The meaning of the phrase ‘such proposed amendment or amendments shall be submitted to the voters’ is plain and its direction is clear: The amendment is to be presented to the people for a vote,” Chief Justice John Minton wrote in the decision.

This year, the entire 614-word amendment appears on the ballot. The measure would provide crime victims with specific constitutional rights, including the right to be treated with fairness and due consideration for the victim’s safety, dignity, and privacy; to be notified about proceedings; to be heard at proceedings involving release, plea, or sentencing of the accused; to proceedings free from unreasonable delays; to be present at trials; to consult with the state's attorneys; to reasonable protection from the accused and those acting on behalf of the accused; to be notified about release or escape of the accused; to have the victim's and victim's family's safety considered when setting bail or determining release; and to receive restitution from the individual who committed the criminal offense.

There are at least two groups – The Kentucky ACLU and the Kentucky Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers – that have expressed opposition to Marsy’s Law. The ACLU said in a press release if the laws in place aren’t serving victims, to amend the laws and not the constitution.

The ACLU asserts Marsy’s Law, “uses inconsistent and confusing language that would be at odds with Kentuckians’ constitutional rights, create significant unintended consequences and

deny victims a path to seek legal remedies for violations of their rights.”

The ACLU also contends Marsy’s Law provides no guidance to lawmakers or judges on how to prevent violations of the rights guaranteed to all people by the U.S. Constitution and addresses “real financial concerns” by creating a need for substantial additional resources but “does not allocate any.”

Its effect will be to further burden, muddy and confuse an already overwhelmed system, which will hurt victims and defendants alike,” according to the ACLU.

“If the voices of complaining witnesses and victims are not being heard, it is because prosecutors and judges are not following the statutes that already protect these rights,” according to a statement from the Kentucky Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers. “The solution is not to create a constitutional amendment that weakens your constitutional rights if you, a friend or family member is accused of a crime.”

Supporters say Marsy’s Law is necessary because state courts sometimes fail to take crime victims’ concerns into account, moving cases along to conclusion without even communicating with the people who were most seriously hurt by a crime. Even where there are existing laws, such as victim notification before an inmate is released, mistakes happen, and when they do, victims don’t have much legal recourse, according to a statement from supporters in the Lexington Herald-Leader.

Constitutional Amendment 2, which also appears on the ballot in its entirety, would increase the term of commonwealth’s attorneys from six to eight years beginning in 2030 and increase the term of district court judges from four to eight years beginning in 2022. It would also require district judges to have at least eight years of legal experience. Currently, the requirement for district judges is two years.

Amendment 2 was sponsored by Republican Representatives Jason Nemes, Derek Lewis, C. Ed Massey, and Speaker David Osborne.

“If we have the commonwealth’s attorneys at six years, and the circuit judges at eight-year terms, it makes re-circuiting very difficult. [The amendment] would align the district judges’ terms with all the other judges,” Nemes said.

Concerning the increase in experience for district judges, Nemes said doing this would increase the qualifications and the professionalism of the judiciary.”

Fourteen Republican legislators voted against the bill, seven did not vote, and 16 Democratic legislators did not vote. Sen. Wil Schroder (R), who voted against the bill, said he supported increasing the legal experience requirement for district judges, but “that eight-year terms are really long for any judge and for any elected official in Kentucky.”