LOUISVILLE, Ky. — Today, the University of Louisville released the results from Phase II of it's Co-Immunity Project, showing higher-than-expected rates of exposure to coronavirus in Jefferson County.

What You Need To Know

- Co-Immunity Project releases results from second phase

- Results show higher exposure to coronavirus in Louisville than previously thought

- Researchers sampled nearly .4 percent of Jefferson County

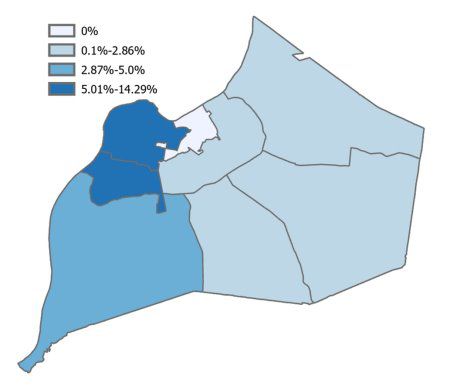

- Results also show concentration of coronavirus cases in Louisville's West End

More specifically, those rates are four to six times higher than previously detected.

Researchers gathered the results over the period of June 10 to 19, testing Louisville residents for both the virus and antibodies. The samples were collected at five community drive-up locations across Louisville by UofL Health and researchers from UofL's Christina Lee Brown Envirome Institute. UofL's Center for Predictive Medicine for Biodefense and Emerging Infectious Disease (CPM) analyzed those samples in its Regional Biocontainment Laboratory (RBL).

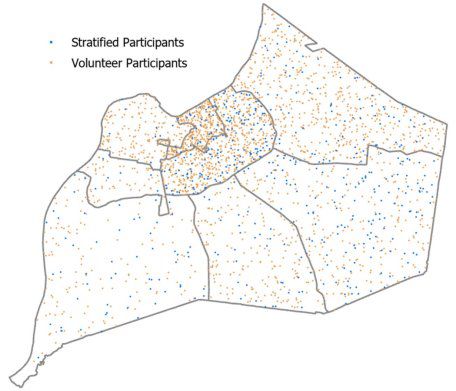

The study organized Jefferson County households into geographic regions so that researchers could obtain a representative sample. Households in each region received invitations to participate in proportion to the region's population, and areas that had higher concentrations of non-White residents were sampled at a higher rate to increase their representation.

In total, invitations were mailed to 18,232 addresses. One adult from each household was asked to provide a sample based on the ages and sexes of all adults in the household, provided by responses to the invitation.

Researchers tested 509 people who responded, and an additional 1,728 people booked appointments on their own and were tested. A total of 2,237 people were tested, 10 percent being non-White.

The breakdown of participtants' ages is:

- 21 percent between 18-34

- 40 percent between 35-59

- 40 percent age 60 or older

Nearly 0.4 percent of Jefferson County's population was sampled.

According to the data, at least 0.05 percent of partipants had an active infection when they were sampled, and roughly 4 percent had antibodies, meaning they had the virus at some point in the past.

“These results allow us, for the first time, to more accurately estimate the spread of coronavirus within our community. If we extrapolate the results from this study to the general population, it would suggest that as many as 20,000 people may have been exposed to the virus – many more than the 3,813 cases reported in the city by the end of June,” said Aruni Bhatnagar, Ph.D., director of the Brown Envirome Institute.

This discrepancy may be because residents didn't realize they were infected since they weren't showing symptoms.

“We were told by several participants that they believed they had COVID-19 before testing was widely available. Nonetheless, our preliminary data suggest that the estimated number of people who have had COVID-19 may be 4-6 times higher than those who have tested positive to-date,” said Rachel Keith, Ph.D., assistant professor of environmental medicine at UofL who conducted the study. “This suggests that the virus is much more widespread in our community than previously estimated. I believe this indicates a need for continued and widespread testing, including antibody testing, which plays an important role in understanding the spread of disease.”

“The random sampling of the population also allows us to calculate the true mortality associated with COVID-19,” Bhatnagar said. “Previous estimates of COVID-19-related mortality have varied from 0.5 to 15 percent. However, given that the city had reported 209 deaths by the end of June, our results suggest that the rate of mortality associated with the virus, at least in Kentucky, may be 1.3 percent. This is significantly higher than the 0.65 percent rate suggested by the CDC. Our research suggests that many who are infected with the virus nationwide have not been tested and that there is urgent need to continue random testing so that we can calculate the most accurate mortality rate."

The data also gave an idea on how the virus had spread in different parts of Louisville.

“Because participants were drawn from all parts of the city, we could estimate which areas have had the highest rates of infection,” Keith said. “Although we are still analyzing all our data, our early results show that the highest cluster of individuals exposed to the virus is in Western Louisville. (See Map 2, below). We found that the prevalence of exposure was twice as high in non-White participants as in White participants. Most (54 percent) of those who tested positive for the antibody were between the ages of 35-59 years old,” she said.

Due to the changing nature of coronavirus, researchers warned that these results are only applicable to the window when samples were collected, June 10 through 19.

“Although many individuals had detectable levels, the amount of antibodies in blood varied greatly among the participants,” said Kenneth Palmer, Ph.D., director of the CPM. “As a result, we are not sure to what extent they are protected from re-infection. Indeed, some of our early results show that the levels of antibodies decline rapidly within a month. Therefore, we are planning to re-measure individuals who had antibodies in their blood to see if those levels are maintained over time and if so, for how long.”

The Co-Immunity Project is still going. Now, researchers are repeating the antibody test in health care workers found to have coronavirus antibodies during the project's first phase. In September, the project will repeat community-wide testing in Louisville.