LOUISVILLE, Ky. — There are growing conversations and concerns about a group of man-made chemicals collectively known as Per-and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances, or more commonly known as PFAS. PFAS have been in the U.S. since the 1940s.

They repel oil and water so they have been used in many products like non-stick cookware, food packaging, clothes, cosmetics, and some firefighting foams, just to name a few. There are 5,000 types of PFAS, and they are sometimes referred to as “Forever Chemicals” because of their persistence in the environment and our bodies.

“So we've been exposed to them for a long time. In fact, it's hard to find somebody who doesn't already have them in their serum,” said Kelly Pennell, Associate Director of the University of Kentucky’s Superfund Research Center. Research is focused on how contaminants, including PFAS, change and travel in the environment, and their ultimate exposure risk for people.

“So there's many different conveniences and important safety that's been provided by these [PFAS]. However, they were not managed properly in the environment,” Pennell said. PFAS levels in the blood are due to eating food or drinking water with PFAS in it. For example, emissions, leaks, and spills from original PFAS users, such as a manufacturer, can spread PFAS into the atmosphere or groundwater, which can lead to PFAS detection in drinking water.

The level of detection in drinking water at which PFAS exposure would create adverse health effects has been researched and is ongoing. There is currently no federal regulation regarding PFAS levels in drinking water. Tests that can detect individual PFAS, since there are nearly 5,000 types, are also continually being developed. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has developed methods to detect 29 PFAS.

A recent report by the Environmental Working Group or EWG, non-profit research and advocacy environmental health organization, tested for 30 PFAS in drinking water in 44 locations – including Louisville. Their result using a modified EPA testing method showed eight PFAS detections from a sample of tap water collected in Louisville.

“It means there's PFAS in the water levels that likely cause health effects. The point of this testing was to spur more testing, more in-depth testing of various water systems across the United States,” said EWG Science Analyst, Sydney Evans, who also co-authored the report.

EWG collected one sample of tap water in Louisville by a volunteer at an undisclosed location. EWG’s report stated samples “are likely representative of the water in the area where the sample was taken but are not intended to identify specific water systems.”

Kelley Dearing-Smith with the Louisville Water Company disagrees with EWG’s report.

“You know, one sample, at one point, at one time, is not indicative of what your drinking water is, and so to call that there's something wrong with your drinking water is really misleading because Louisville’s drinking water is absolutely safe and high quality,” Smith said, who is the Vice President of Communications and Marketing for Louisville Water Company.

Smith said LWC performs over 200 tests on its drinking water daily in an EPA certified lab. However, PFAS is not part of the test because the instruments are expensive and PFAS isn’t currently regulated. Smith said LWC has monitored several PFAS on a weekly to quarterly basis at an outside lab since 2013.

“So it’s a balancing act. It’s making sure that our scientists here can focus on the things that are regulated, the things that we have to make sure that are absolutely perfect, and then balancing all of the other additional research that we are doing,” Smith said.

On November 18, 2019, Kentucky’s Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) published an evaluation of eight PFAS levels tested for at 81 water treatment plants in Kentucky, which included results of three PFAS detections from LWC’s two treatment plants. DEP used standard protocols compared to EWG.

“So it's not just Louisville [that has PFAS levels in drinking water], I want to point out it's actually an entire problem across the country and then further even the world,” Pennell said. “Also, this is something that we've actually had in our water for probably many, many years, and is something we're just learning about, and I think that it's important that as we learn, we do make informed decisions.”

The two most studied PFAS chemicals, Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS) and (Perfluorooctanoic Acid) PFOA have been voluntarily phased out in the U.S. but can still be imported in overseas products.

Studies have shown exposure over certain levels to PFOA and PFOS can cause adverse health effects.

In 2016, the EPA established a health advisory level at 70 parts per trillion (ppt) for both PFOA and PFOS in drinking water. However, a health advisory is non-enforceable and non-regulated, as it’s an advisory.

EWG and DEP’s reports found PFOA and PFOS levels for Louisville below EPA’s health advisory level of 70 ppt. EWG’s tap water sample on July 29, 2019, showed PFOS detection at 2.6 ppt and PFOA at 7.7 ppt. DEP’s report, which sampled on July 1, 2019, showed a PFOA detection of 2.75 ppt and PFOS at 1.55 ppt at the Crescent Hill treatment plant, which gets its water from the Ohio River. DEP’s report also showed PFOA at 4.31 ppt and PFOS at 1.34 from the Payne Plant, which gets its water from an aquifer.

However, the differences between EWG and DEP’s sampling dates, location, and testing standards can all contribute to the different levels.

“The date of the sampling really does matter because it matters on weather conditions, where was that intake for that source water that was supplying that tap water? All of those things are extremely important to determine water quality,” Pennell said.

LWC did not provide a report to Spectrum News 1 on their PFAS detections. However, Smith stated in an email that LWC has detected for four PFAS since 2013, and PFOA levels range from 2.6 to 13 ppt and PFOS ranges from non-detect to 4.8 ppt.

DEP’s report concluded that although PFAS was detected in finished drinking water, their occurrences were “generally infrequent and at concentrations well below” the EPAs health advisory of 70 ppt. So the DEP determined that there are no evident health concerns in the Commonwealth’s public drinking water supply.

“I believe that Kentucky is relying on EPA’s health advisory level of 70, and EWG, I believe, is comparing their levels to [1 ppt] for a total PFAS. As a researcher, I look at kind of where the research is heading, and it definitely does show that as we learn more about these compounds, we do have reason to think that the 70 may not be totally protective of all the health effects we're seeing, but we're still learning more,” Pennell told Spectrum News 1.

In March 2019, Kentucky passed a law that bans the use of class B firefighting foam for firefighting training purposes or testing purposes. That foam, which has PFAS, has been a source of drinking water contamination. The law goes into effect on July 15, 2020.

Last month the U.S. House passed a bill that would set deadlines for the EPA to set PFAS drinking water standards, which is now in the hands of the senate.

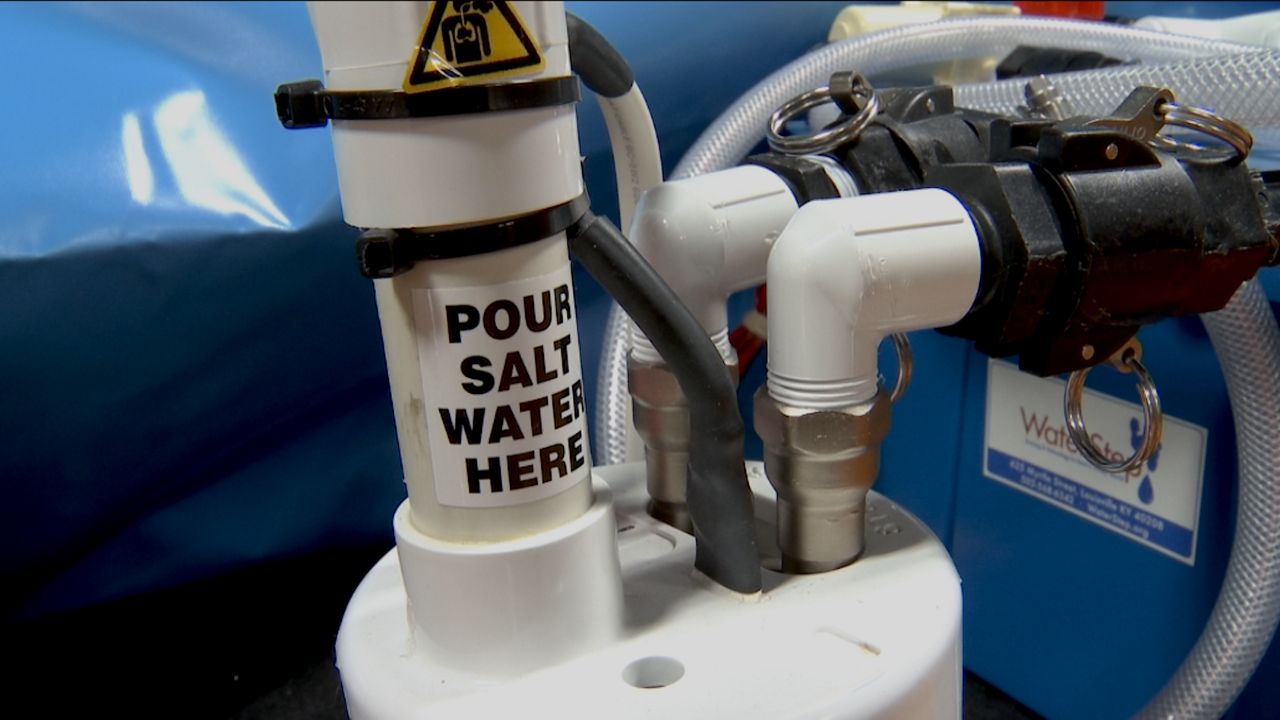

For now, Pennell said to be careful with turning to another source for water because bottled water is also not regulated for PFAS since currently no drinking water is regulated federally. Carbon-activated or reverse osmosis in-home water treatment systems have been shown to remove PFAS.

In a statement to Spectrum News 1 asking about EWG’s recent report, an EPA spokesperson stated in part, “EPA’s PFAS Action Plan commits the agency to take important steps that will enhance how the agency researches, monitors, detects, and addresses PFAS. Over the past year, EPA has made significant progress under the Action Plan to help states and local communities address PFAS and protect public health…To date, EPA has developed methods to reliably detect 29 PFAS chemicals in drinking water. Aggressively addressing PFAS will continue to be an EPA priority in 2020 and we will provide additional information on our upcoming actions as it becomes available.”

Evans says there is still a lot more that needs to be done.

“There is no regulation of these compounds; there's no requirement to test and when PFAS is found, there's no required requirement to remove it from drinking water at the national level. So there's still a very, very long way to go to solving this problem, which is not new. This has been ongoing for decades,” Evans told Spectrum News 1.

Smith said LWC would continue to monitor PFAS.

“We are well below that standard. Does that mean we take our eyes off of it? Absolutely not. The EPA has not regulated this so right now local utilities, like Louisville Water, are doing our own monitoring, and we're trying to determine what is the picture of this particular contaminant in our drinking water,” Smith said. “But when customers ask me well what can I do as a consumer, we need to ask Congress to give us funding for research to let this process continue. We didn't create the problem; we're trying to fix it now.”

Pennell said at this point scientists are still learning more about the toxicity of PFAS.

“So just because we have been exposed for several years doesn't mean to not do anything, but we also need to be aware that these are difficult decisions to make. As a researcher, I know that it warrants additional investigation. We need to continue looking into it; we need to get better information,” Pennell said. “And we need to continue sampling additional locations in Kentucky, and we need to find out where the sources of these chemicals are so that we can stop those and then protect our drinking water.”

To view EWG’s other PFAS detections for the Louisville tap water sampled visit page 6 here .

PFAS detections for the 81 Kentucky water treatment plants that DEP sampled can be found in Appendix D, starting on page 68 here.