Click here to watch Part 1: "The Cash Crop"

Click here to watch Part 2: "Black Entrepreneurs"

Click here to watch Part 3: "The History of Hemp in Kentucky"

THE CASH CROP

Click here to watch Part 1: "The Cash Crop"

In America, Black farmers make up less than 2 percent of all farmers in the country, owning just 0.4 percent of all U.S. farmland, according to the United States Department of Agriculture Census.

It’s a confounding reality given African Americans historic relationship to the soil but some farmers hope a newly legalized cash crop, hemp, can eventually equal the playing field.

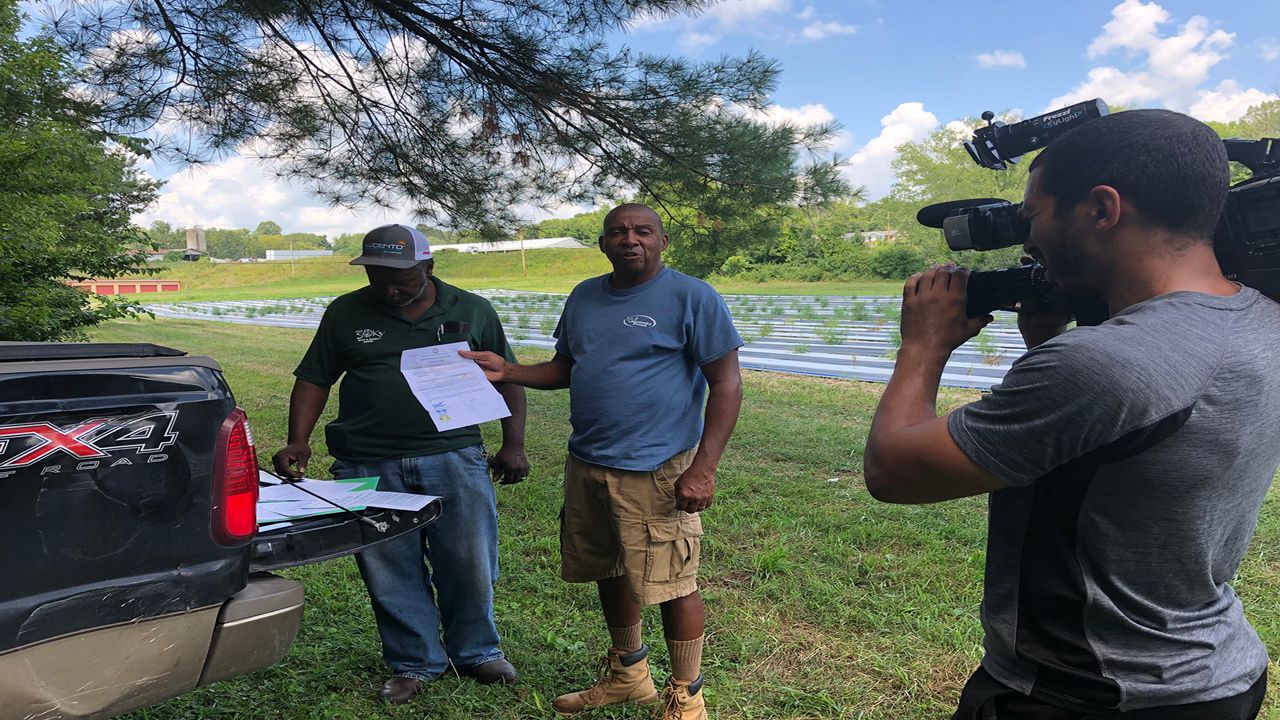

“Everybody was worried about the legal aspect of it. I’m retired from the military. Of course, you don’t want to do anything that would mess with your retirement and your benefits. You don’t want to lose the potential property that you have,” said Joe Trigg, a Glasgow, Kentucky farmer.

Trigg had his trepidations about hemp. The Cannabis plant can make more than 25,000 products -- everything from rope, to cable, to bioplastics, but because of its close association to marijuana, it was federally banned in 1937, only to be resurrected when the Farm Bill was signed into law on December 2018.

Due to the disproportionate criminalization of Black Americans possessing marijuana, Trigg was understandably cautious. According to the ACLU, Black Americans are nearly four times more likely than Whites to be arrested for marijuana.

Though hemp is not a psychoactive drug, he didn’t want to do anything to put his land in jeopardy.

“If you own a piece of this here great country of ours then that puts you at a different category. You are a landowner. You’ve got property. You’ve got something that others will loan money against. You’ve got equity,” said Trigg.

After his failed attempt to become Kentucky’s next Agriculture Commissioner, he decided to take a chance, in hopes hemp will be a lifeline for small farmers like him. He’s raised beef cattle through Trigg Enterprises with his family for more than thirty years. Though he’s all in on hemp, investing about $15,000 on 1.5 acres, he has concerns about the potential for monopolization among industrial agricultural corporations.

“You can’t compete. This trickle-down effect that everybody keeps wanting to harp on. I’m here to tell you there’s only two things that trickle down on a farm, it’s some poo and some pee.”

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell introduced The Hemp Farming Act of 2018 that ultimately led to hemp being removed from the Schedule I controlled substances list. Kentucky’s Agriculture Commissioner Ryan Quarles acknowledges Trigg’s fears but says no farmer will be left behind.

“The small hemp grower is actually succeeding right now because hemp is different. Unlike tobacco, corn, and soybeans, where you grow it in a similar way, hemp is grown differently depending on what the final product is and say like a CBD crop, it will be grown a lot differently than a grain crop or a fiber crop. What we’ve seen is a lot of small farmers are looking at niche markets or they are able to excel and replicate what they are doing across the state,” said Quarles.

The average size of a farm in Kentucky is 169 acres, and a harvest season of soybeans can bring in approximately $84,000. Take out the soybeans and replace them with hemp, a farm of the same size can make an estimated $5 million each season, according to Hemp Business Daily.

Austin Wright, a Small Farms Agent at the historically Black Kentucky State University, agrees with the commissioner. It’s quality, not quantity.

“Hemp is not a crop that you can just drop and grow immediately. You have to be educated. You have to know the law. You have to know the rules. You have to know the science in growing. You can grow organic hemp if you have 2-3 acres. Organic hemp gets a higher value,” said Wright.

A pound of dried hemp flower sells between $20 and $50, all depending on the quality of the Cannabidiol content – also known as CBD. Though he concedes it will be an uphill battle, Wright believes hemp can aid in revitalizing Black farming in America. Of the 75,966 farms in Kentucky, only 333 are fully Black-owned, according to the USDA Census.

“We’re losing 8 out of 10 Black farms almost every quarter,” said Wright.“We’re losing 8 out of 10 Black farms almost every quarter,” said Wright.

“The industry of row cropping for most African American farmers is dying at a high rate and being that hemp is new, it is extremely critical that we have it,” he added.

One of the reasons growing hemp can be risky is farmers have to make sure the crop has less than .3% THC. THC is the component in marijuana that can get people high. Stress or bad weather can up the level of THC and if the authorities find out about that increase, farmers could be forced to burn the crop.

“I’m a fourth-generation family farmer. Ours was kind of left down through the generations by will,” said Ronald Bunton.

Bunton has already invested $10,000 in working to get his hemp operation off the ground in Woodburn, Kentucky. Despite the risks, like Trigg, he’s convinced it’s worth the effort. With $1.1 billion in revenues in 2018, New Frontier Data estimates revenue will grow to $2.6 billion by 2022.

“My dad always taught me if you lose a little money in the beginning, you know not to go back a second time but if it’s money-making, you want to be in on the start as well as on the finish,” said Bunton.“My dad always taught me if you lose a little money in the beginning, you know not to go back a second time but if it’s money-making, you want to be in on the start as well as on the finish,” said Bunton.

Trigg’s son, Joseph Dean Trigg, just 19 years old, has worked the land since he was eight. He says he’s tired of seeing his father struggle and is relying on hemp to carry on the family tradition.

“The amount of work that my father and his brothers and cousins have put into it, I don’t want it to go to waste,” he said.

BLACK ENTREPRENEURS

Click here to watch Part 2: "Black Entrepreneurs"

Clinton Carter, Jr. was three years old when he fell off of a third-floor balcony onto a concrete patio. Carter said, I hit my head and bit a hole in my cheek. My mother thought I was dead."

When Carter abruptly stopped smoking marijuana last year, he soon realized he may have been unconsciously self-medicating for nearly his entire life following a host of injuries from childhood.

"In the last six months of last year, I had seven seizures," he said.

His longtime friend George McGill recommended CJ use a hemp-derived CBD capsule. The seizures stopped.

"I know what works for me. I know what my medicine is. I know what it’s made of. It’s third party tested and it comes from mother nature," said Carter.

Together they run Comfy Hemp, an online business, selling tinctures, salves for hip and back pain and CBD protein.

"We launched Comfy Hemp specifically to market to multicultural consumers as well as veterans with an intent to provide a price point that was more conducive to our consumers' pocketbook," said McGill."We launched Comfy Hemp specifically to market to multicultural consumers as well as veterans with an intent to provide a price point that was more conducive to our consumers' pocketbook," said McGill.

Born and raised in Louisville, McGill, a former corporate marketing executive who studied finance at the University of Kentucky, has no illusions about getting rich off of hemp. He views the company as a boutique-style operation but even with measured expectations, it was tough to launch the company. The rules for advertising and promoting CBD businesses on social media are unclear and the federal banking regulations are murky as well. The American Bankers Association says they are seeking clarity from the federal government on distinguishing between legal hemp and federally illegal marijuana, leaving many banks unwilling to work with CBD businesses. Black business owners are three times more likely to say a lack of credit is their biggest challenge, according to a 2017 report from the Association for Enterprise Opportunity. Loan denial rates for minority-owned businesses are about three times higher, at 42 percent, compared to those of non-minority-owned companies.

When asked what obstacles African-American distributors face, McGill responded, "Capital. Funding. Having the right type of capital to fund these types of operations. Unfortunately because of the wealth gap in multicultural communities, when you get a once in a lifetime opportunity like the cannabis/hemp industry if you don’t have necessarily a lot of already acquired wealth to pay for the machinery, pay for the labor. It can be a very difficult hurdle. It can be a very emotional task because you know you have a great opportunity but you know the competition, especially for myself, they have a lot more capital than me."

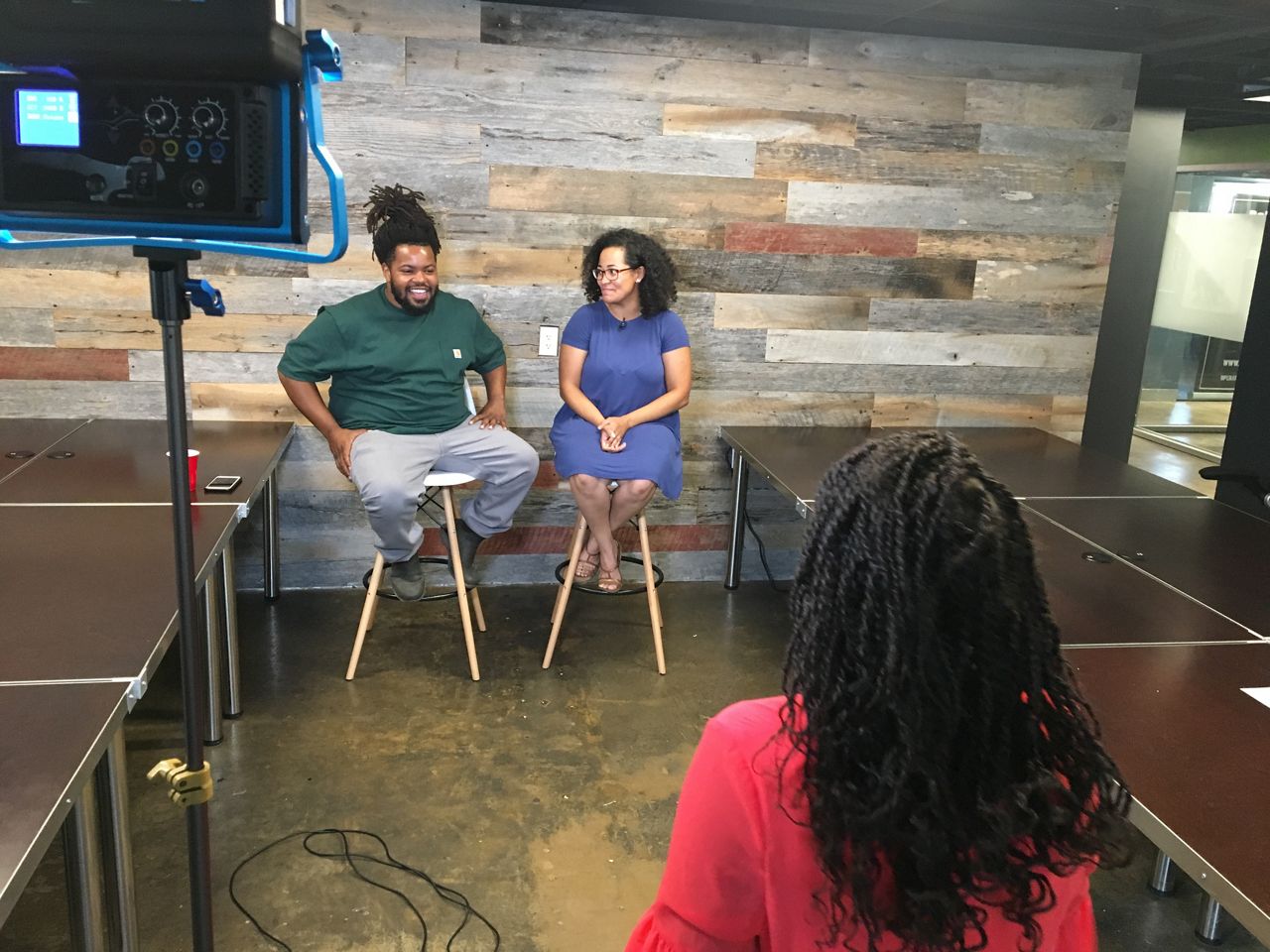

George and CJ are part of a larger movement of Black millennial entrepreneurs who meet in co-working spaces like this one in downtown Lexington, Kentucky. Charles Jones, who also goes by C.J., and Sasha Johnson run the online business S'Hemply Made. They work closely with Black farmers and specialize in skincare products like hemp lip balm and body butter.

Jones says, "Through history, I saw the trials and tribulations that Blacks had in relation to farming and I also thought I wanted to be involved in my community and how would I do that and it was like I know I’m not going to be a big speaker like a Malcolm X. So I was like, well OK, my other angle could be farming."

"It’s been wonderful," said Johnson. "The support that we got here locally has been amazing because we pretty much make products that are 100% natural, that are safe for people to use on their entire families and that are priced in such a way that they are accessible."

They view this work as a part of a larger mission rooted in social justice and are concerned about how the hemp felon ban impacts communities of color. According to the Farm Bill, which legalized hemp in December 2018, anyone convicted of a drug-related felony is barred from participating in its production for 10 years after their date of conviction, unless they were part of the 2014 hemp pilot program in their state.

Jones told Spectrum News 1, "I myself have had run-ins with the law in the cases of marijuana. It’s nothing that I’m ashamed of because I don’t feel anything wrong right there but I know how it feels to be treated in such a way over a plant…parade me, strip search me, all that for weed."

Johnson said, "I know so many people have been criminalized due to cannabis use and I really want to see a shift. I mean I feel like I have an actual responsibility to be a part of that shift. "Johnson said, "I know so many people have been criminalized due to cannabis use and I really want to see a shift. I mean I feel like I have an actual responsibility to be a part of that shift. "

The pair hope the legalization of hemp will eventually lead to the legalization of marijuana. Johnson said, " We are going to see this all the way through. It’s a long shot. We know that when those marijuana licenses roll out that there are going to be few of them granted to the state so even fewer for a person of color but we are going to be right there waiting in line."

According to the Department of Labor, the average age of an American farmer or rancher is more than 50 years old. Anecdotally, Black farmers in Kentucky believe that median age skews slightly higher among them. They hope hemp can inspire a new generation.

Lamar Wilson created Sunjoined earlier this year. It’s a fundraising network he maintains largely online made up of farmers, distributors, and processors across the hemp industry.

"The power of all of us working together changes everything. As a collective, we can have far more acres of hemp than a Monsanto as a collective, so why not build that collective and all work together."

Hemp retail sales in the U.S. grossed an estimated 1.2 billion dollars in 2018. The software developer from Lexington is convinced hemp can trigger a redistribution of wealth in America.

"Black farmers are an endangered species right now. If we can bring value back to them by working with companies like Comfy Hemp, by working with the S'hemply Made’s, they all need product," Wilson continued, "This is the one time in history that Black people that African Americans that come from America, have had access to a resource at the ground floor. That changes things. When you have access when you actually have access, that allows you to have a force multiplier on your ability to generate wealth."

Johnson says she is taking a wait and see approach, "I’m still waiting to see like everybody else. I want to see the real numbers because from what I’ve seen, it seems like people are just chugging along."

THE HISTORY OF HEMP IN KENTUCKY

Click here to watch Part 3: "The History of Hemp in Kentucky"

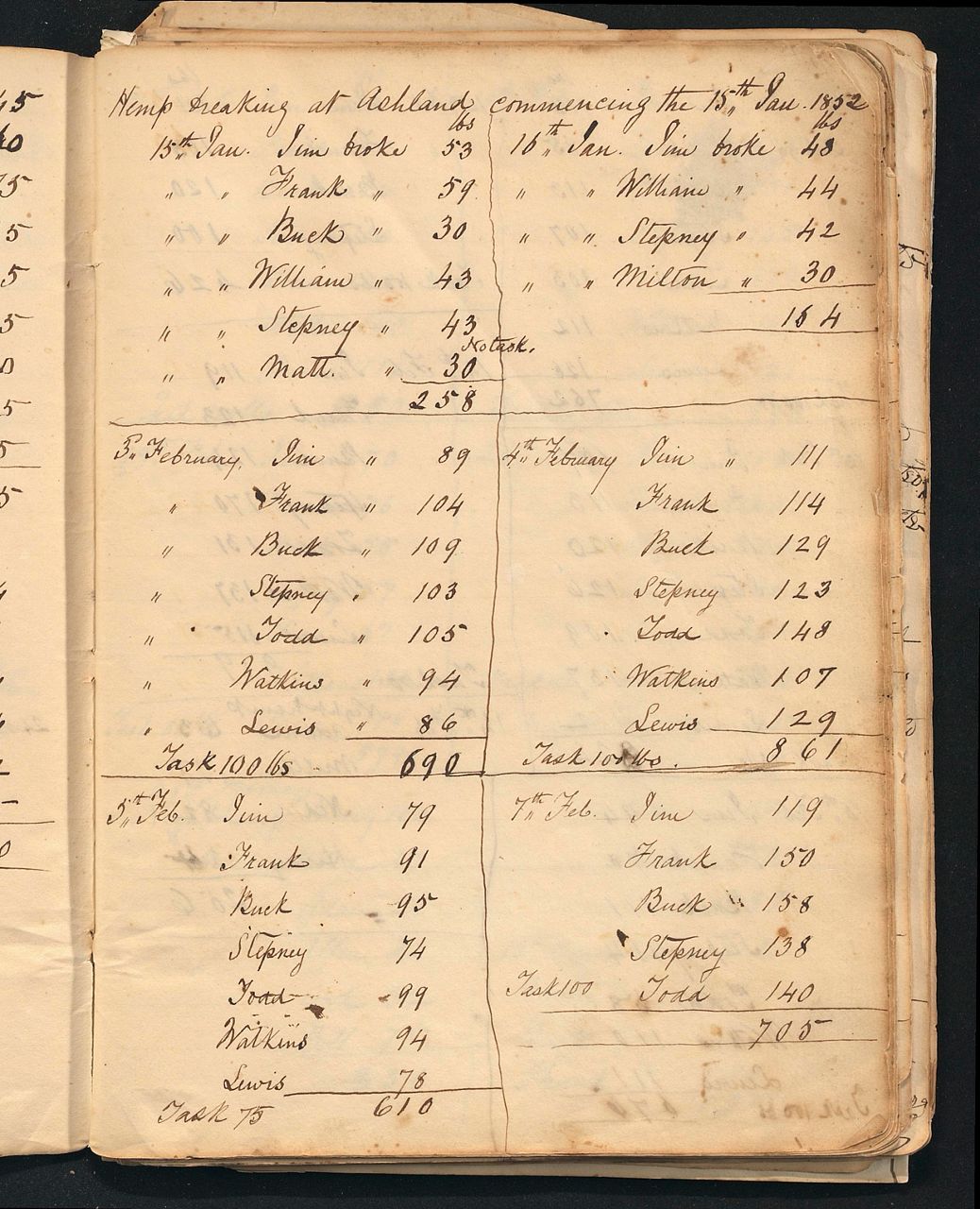

Trevor Claiborn and his partner Ashley Smith are on a mission to get people to think critically about the history of hemp. They are the founders of an advocacy group called Black Soil: Our Better Nature, which works to celebrate the heritage and legacy of Black agriculturalists in Kentucky. As hemp enjoys a renaissance, they are determined to elevate its Black roots.

“When North America gained the wealth that it has, it was on the backs of our ancestors,” said Claiborn.“When North America gained the wealth that it has, it was on the backs of our ancestors,” said Claiborn. “Black people mastered this art that made us such a rich nation,” he added.

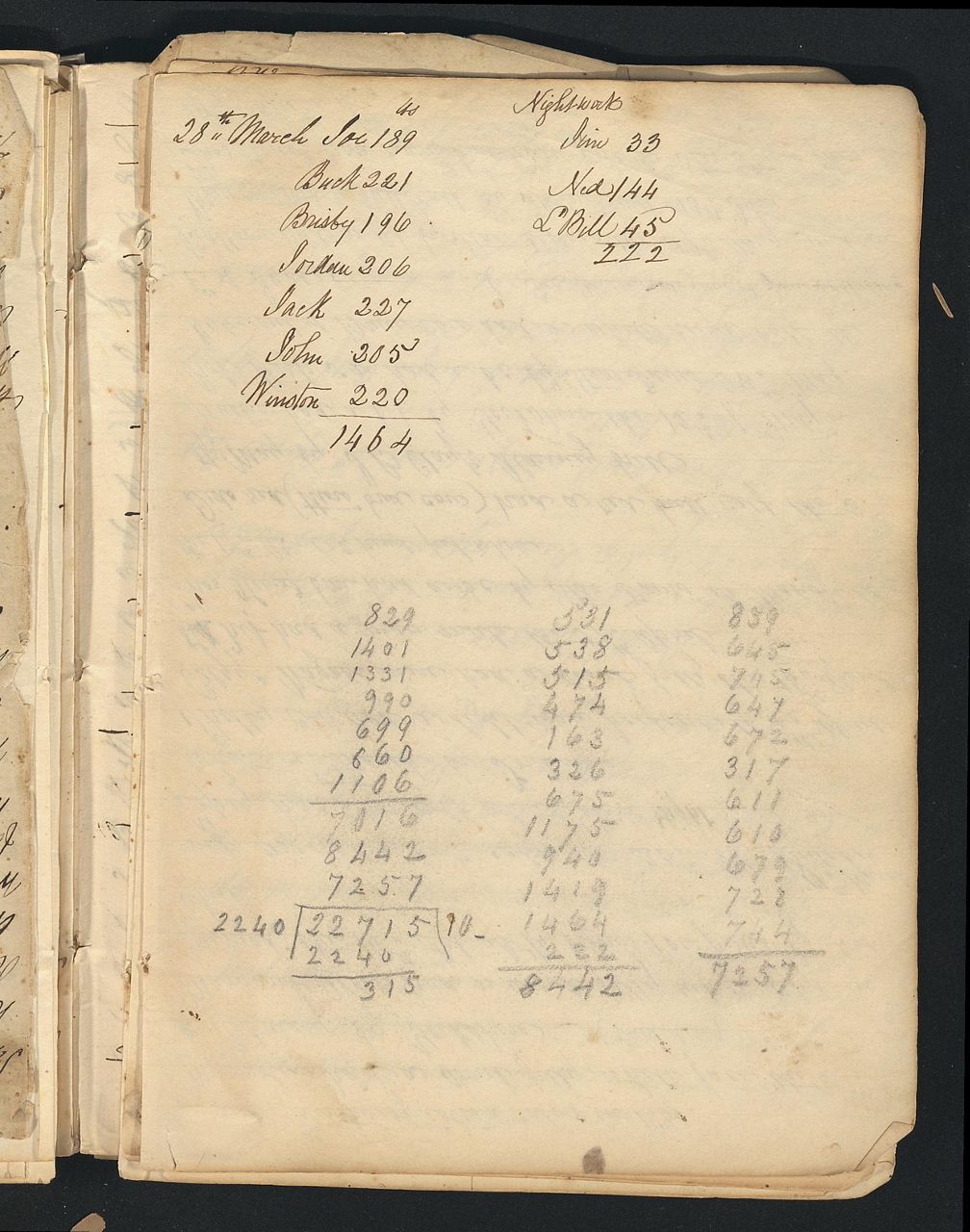

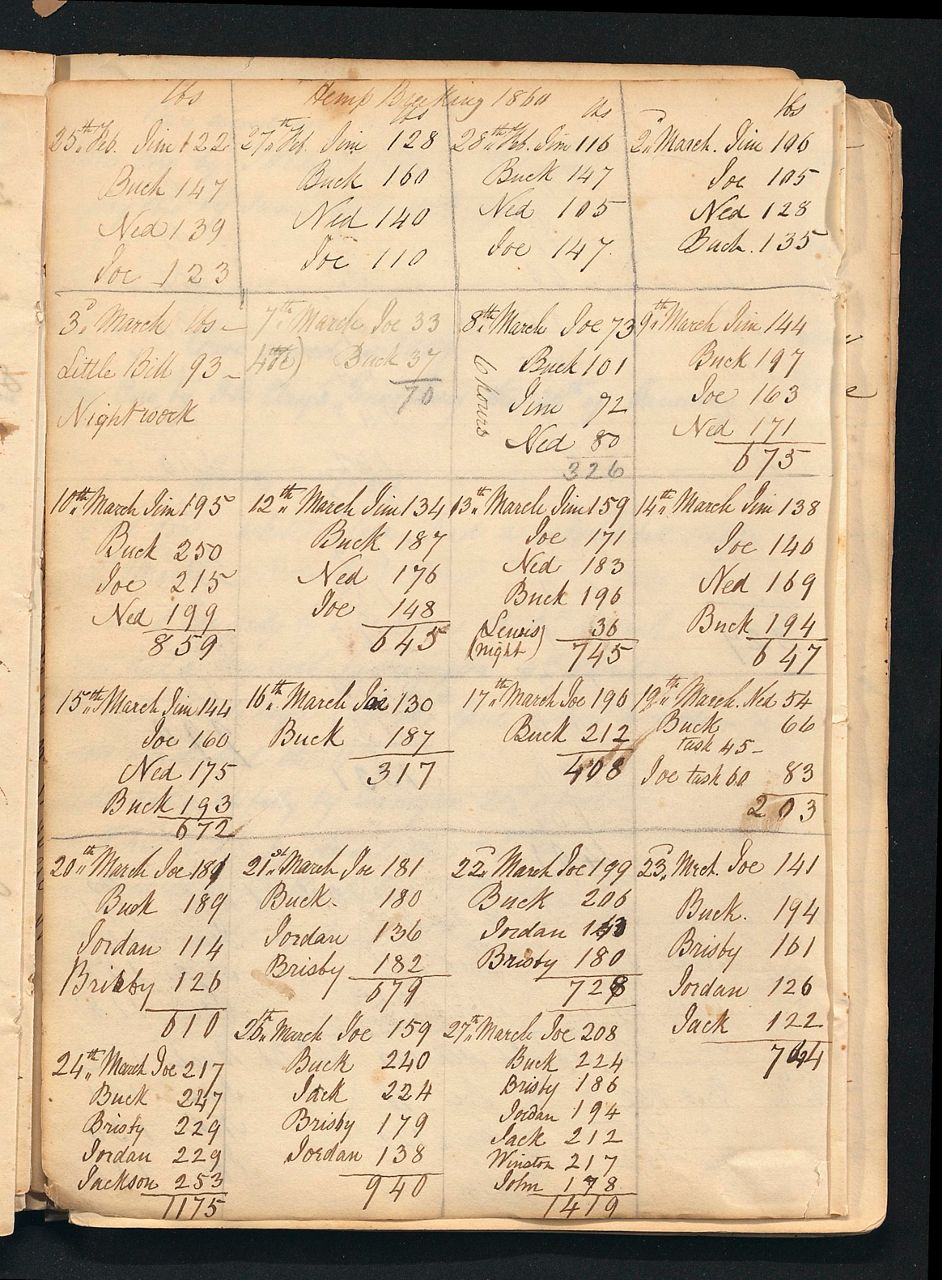

As noted by historian James Hopkins in his 1951 book, A History of the Hemp Industry in Kentucky, “It is a significant fact that the heaviest concentration of slavery was in the hemp producing area.” Smith and Claiborn fear those slaves will be erased from the retelling of hemp’s story.

During a July Senate Agriculture Committee hearing on hemp production, Michigan’s Democratic Senator, Debbie Stabenow reflected on the history of the crop.

“This exciting new opportunity is actually part of a great American tradition. George Washington, John Adams, and Thomas Jefferson all grew hemp. In fact, maybe Lin Manuel Miranda will make his next musical about that,” she said.

“Henry Clay as well,” Senate Majority Leader and Kentucky’s Senior Senator Mitch McConnell, chimed in.

“Henry Clay as well. Thank you, Mr. Leader,” Stabenow replied as the room erupted in laughter.

Smith says she witnesses a subtle erasure of slavery that is concerning.

“Uplifting the historical figure of Henry Clay, but if you understand the timeline of his career and the agricultural innovations of Ashland, Mr. Clay was in Washington, D.C. for twenty-five years,” she said. “There were tons of innovations happening around hemp. We have to dial back and ask who were those hidden figures leading the charge, out in the fields, breaking the stalks?”

“When a lot of these innovations were being developed, Black people weren’t in a position to get patents for them,” said Claiborn.

In advocating against abolishing slavery, William Bullitt, a Kentucky delegate to the constitutional convention of 1849 pleaded to keep the institution alive to maintain the production of hemp. According to Hopkins, Bullitt said, “Take away slaves and you destroy the production of that valuable article.”

A recent investigation by The Atlantic outlined how even well after slavery ended, systemic discrimination “dispossessed 98% of Black agricultural landowners in America.” At least one group, Minorities for Medical Marijuana, is pushing for anti-discrimination language to be written into future federal hemp legislation.

“Not only written into law but it has to be enforced,” said Claiborn.

“But how are you going to enforce it? Who is going to make sure that it is enforced on the local level,” Smith said.

The 2018 Farm Bill includes $435 million over ten years that’s designated, in part, to training and outreach programs for underserved farmers.

Former University of Kentucky basketball star and retired tobacco executive, Merion Haskins, doesn’t share their concerns. The Greensburg farmer is reluctant to reflect too deeply on the historical context of hemp at all.

“Hopefully we’ve moved on,” said Haskins. “We all exited our family farms. We all got educated, went to universities. We got jobs with major corporations and then we left the farm,” he said.

“I have so much confidence because I was at the meeting in Louisville with Senator McConnell and Secretary Perdue and they promised us in 2020 that we would have our federal crop insurance,” said Haskins.

At the invitation of McConnell, United States Department of Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue visited hemp operations in Louisville and Lexington in July..

Regulators from the USDA, Food and Drug Administration and Environmental Protection Agency are working to come up with the rules for the hemp economy. The USDA isn’t expected to roll out a plan for hemp crop insurance until next year. Still, Haskins got involved because he says given Kentucky’s once-thriving tobacco economy, the infrastructure is ripe for hemp.

“I think it’s going to benefit everyone. We will be adding to the tax base. We will be employing people,” said Haskins.

For brother and sister, Paul Price and Jan Brazley in Hodgenville, it’s also about the dollars and cents.

“I am a retired school teacher who has taken up the profession of farming. I’m working harder now than I’ve ever worked in my life,” said Brazley.

While it saddens her that so many Black farmers have not been able to hold onto their property, she doesn’t view the work as something she wants to pass along to her children.

“We have started maybe a revolution. I don’t know and other people can see our story and be encouraged that they can do the same thing. I’ve committed for 5 years and after I’m out. I will be almost 70,” she said..

“For me personally, it was the money,” said Price.

A retired government contractor, he also describes this venture as primarily a business investment but because he’s a Black farmer, he says he feels a particular need to meticulously adhere to the evolving regulations.

“We are not blind to the fact that we are African American so there are things that we may not be able to get away with that others can,” said Price.“We are not blind to the fact that we are African American so there are things that we may not be able to get away with that others can,” said Price.

But that consciousness isn’t slowing him down. He’s already leaning on his sister to take an even bigger risk by growing a larger amount of hemp next year.

“We always put God in it. We are trusting in the Lord and we believe this is what he has for us to do at this time,” said Price.

Christopher Thomas was chief photographer and editor on the series. Samuel Lisker, Joseph Olmo, and Margaret Cahill assisted with research.