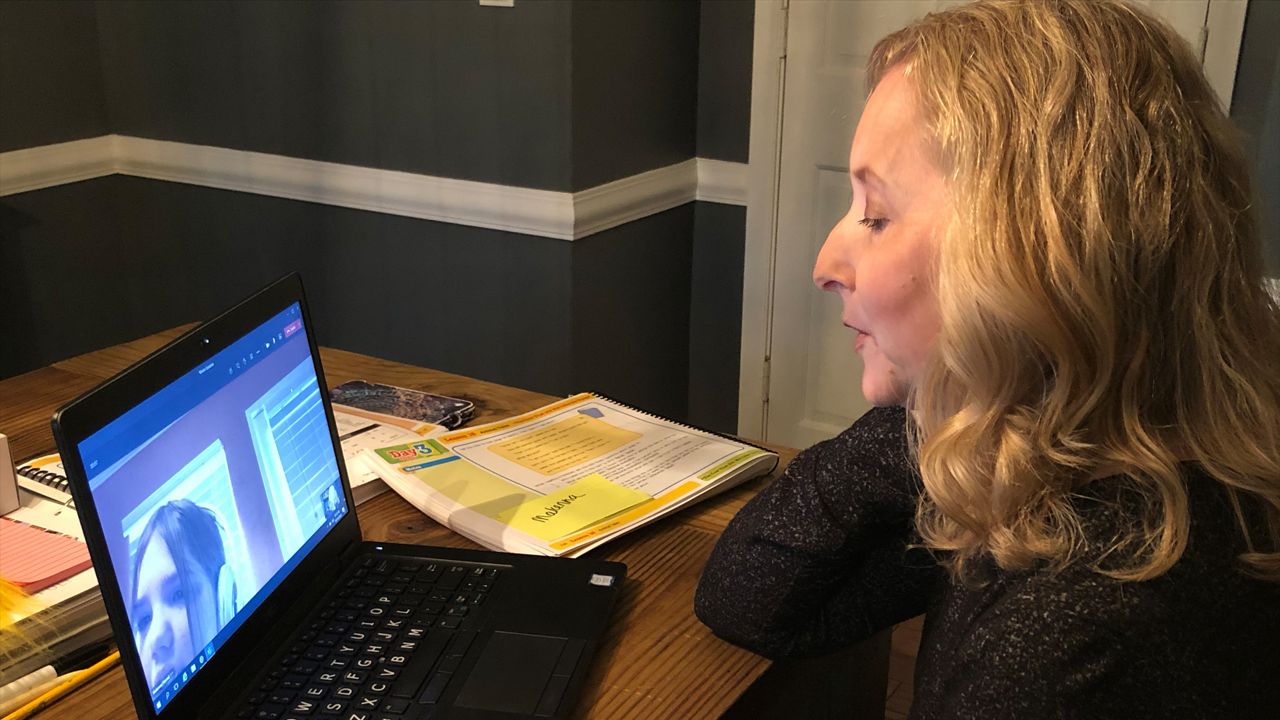

LOUISVILLE, Ky. – It was nine o’clock on a Thursday morning when 11-year-old Makenna Harrod logged onto her iPad for her first virtual lesson of the day. Her teacher, Lori Svoboda, greeted her from her own home, and the hour-long lesson began.

Like many Kentucky students, digital learning has become the “new normal” for Makenna. The Wilder Elementary School fifth-grader has been doing Non-Traditional Instruction (NTI) since March when Jefferson County Public Schools last held in-person classes.

In this particular session, Makenna and Svoboda, who students call ‘Ms. Lori’, read a book together.

“Go away cow! Shoo, shoo!” Makenna said to Svoboda as she read aloud to her teacher from home.

Svoboda asked, “What’s the contraction for ‘go?'”

“A ‘G,'” answered Makenna.

“Which is what dots?”

“One, two, four, five,” answered Makenna.

“Nice work!” said Svoboda.

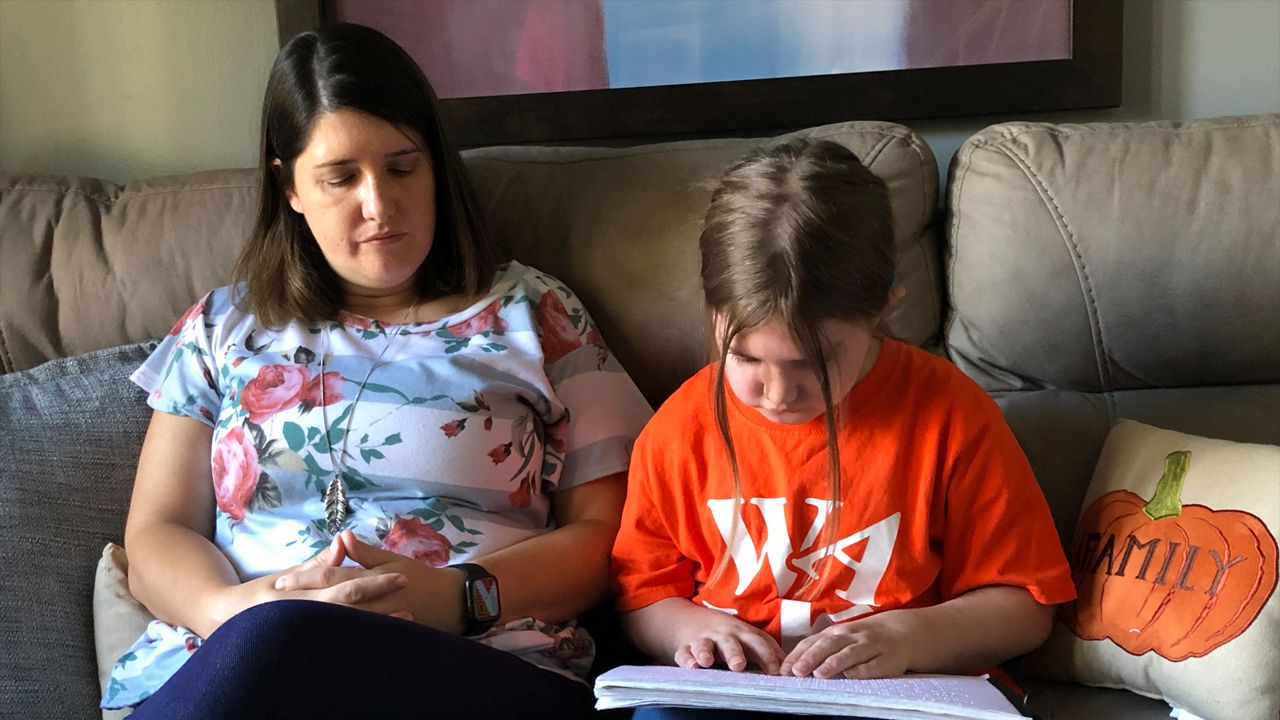

Makenna and Svoboda, a teacher of the visually impaired, were working through a virtual braille lesson. Makenna is blind and hearing impaired. She has Blau syndrome, a rare inflammatory disease that affects her skin, joints, and eyes.

NTI hasn’t been easy for Makenna. Most of her schoolwork is Google-based and her fellow classmates use Chromebooks to complete their assignments. Makenna prefers using an iPad because it is easier for her to manipulate the size of the screen. However, her assignments aren’t always compatible with her Apple device or other assistive technology.

“It’s kind of hard because it’s not really easy to see,” explained Makenna. “I try to see it and I try to do my best on it, but I can’t do it, and with my vision, I take longer to do things and it gets frustrating because I feel like I’m falling behind and I don’t like to be behind in school.”

Makenna only has some vision in one of her eyes, and even with her preferred iPad, she must position the screen directly in front of her eye to see.

“Watching a screen all day is very fatiguing, especially for kids who are visually impaired,” explained Svoboda, who has been helping visually impaired students navigate through the virtual NTI format.

“They’ve been forced to learn a whole lot in a very short amount of time,” said Svoboda, adding that the support she provides parents and students often includes finding “workarounds” to make assignments and technology more accessible. She also works with teachers to ensure their lessons are accessible for visually impaired students. Some of her frequent suggestions include using slides with great contrast, limiting the amount of text on a screen, and using verbal descriptors when showing the class something.

“All the teachers have been so supportive of their accommodations that they need so I really appreciate that,” Svoboda added.

Makenna gets additional help at home from her mom, Mary Harrod, who is also blind and familiar with the online and digital world’s many accessibility obstacles.

“It can be taken for granted that something that can seem so simple can really be a barrier to Makenna with her learning and the teachers have been excellent with making different accommodations for her,” Mary explained.

She said the pandemic has only magnified digital accessibility issues as everyday tasks like schoolwork, doctor’s visits, and grocery shopping all moved online.

“Sometimes we have to choose not to use a certain platform because it’s just not accessible at all and so there’s definitely some gains to be made in that area -- a lot of education and awareness,” Mary said of the limited access she and other individuals with visual impairment encounter daily.

Currently, there are no federally mandated standards for online accessibility. Earlier this month, bipartisan legislation known as The Online Accessibility Act (HR 8478) was introduced to the U.S. House of Representatives. It aims to extend the Americans with Disabilities Act to consumer-facing websites and apps and establish accessibility standards for those platforms.

Democratic Congressman John Yarmuth of Louisville said the legislation hasn’t garnered much support, but said it may be useful in guiding lawmakers in a different direction to tackle the same problem.

“This isn’t only the federal government’s issue,” Yarmuth said. “I think it is certainly something the private sector, as well as the institutions of education at all levels, now have to spend a lot more time thinking about.”

Noting the slow pace of government, Yarmuth expressed concerns about the ability of Congress to effectively set compliance standards for rapidly changing technology. He said there needs to be a new, robust body inside the federal government to deal with technology issues – including accessibility.

Mary said it would be hard to imagine a world in which she or Makenna could open any available website or mobile app, knowing they could use it.

“It would be a huge barrier knocked down for us to be able to access our healthcare and the items we need from the store,” Mary said with a sigh. “It would be life-changing. Our independence would grow even more instead of having to work around and not have as many choices.”

For now, those constant “workarounds” are a reality and frustration for the visually impaired and students who, like Makenna, enjoy their independence.

“I like to do paperwork better than online work because it’s much easier and I like to write,” Makenna said as she explained why she missed in-person classes.

With the support of her teachers and family, Makenna will keep working through NTI until she can return to the classroom. In the meantime, she and her mom hope the pandemic’s sudden shove of society into the virtual world awakens educators, lawmakers, and developers to the vast digital equality gap.