LOUISVILLE, Ky. - Trevor Claiborne and his partner Ashley Smith are on a mission to get people to think critically about the history of hemp. They are the founders of an advocacy group called Black Soil: Our Better Nature, which works to celebrate the heritage and legacy of Black agriculturalists in Kentucky. As hemp enjoys a renaissance, they are determined to elevate its Black roots.

“When North America gained the wealth that it has, it was on the backs of our ancestors,” said Claiborne. “Black people mastered this art that made us such a rich nation,” he added.

As noted by historian James Hopkins in his 1951 book, A History of the Hemp Industry in Kentucky, “It is a significant fact that the heaviest concentration of slavery was in the hemp producing area.” Smith and Claiborne fear those slaves will be erased from the retelling of hemp’s story.

During a July Senate Agriculture Committee hearing on hemp production, Michigan’s Democratic Senator, Debbie Stabenow reflected on the history of the crop.

“This exciting new opportunity is actually part of a great American tradition. George Washington, John Adams, and Thomas Jefferson all grew hemp. In fact, maybe Lin Manuel Miranda will make his next musical about that,” she said.

“Henry Clay as well,” Senate Majority Leader and Kentucky’s Senior Senator Mitch McConnell, chimed in.

“Henry Clay as well. Thank you, Mr. Leader,” Stabenow replied as the room erupted in laughter.

Smith says she witnesses a subtle erasure of slavery that is concerning.

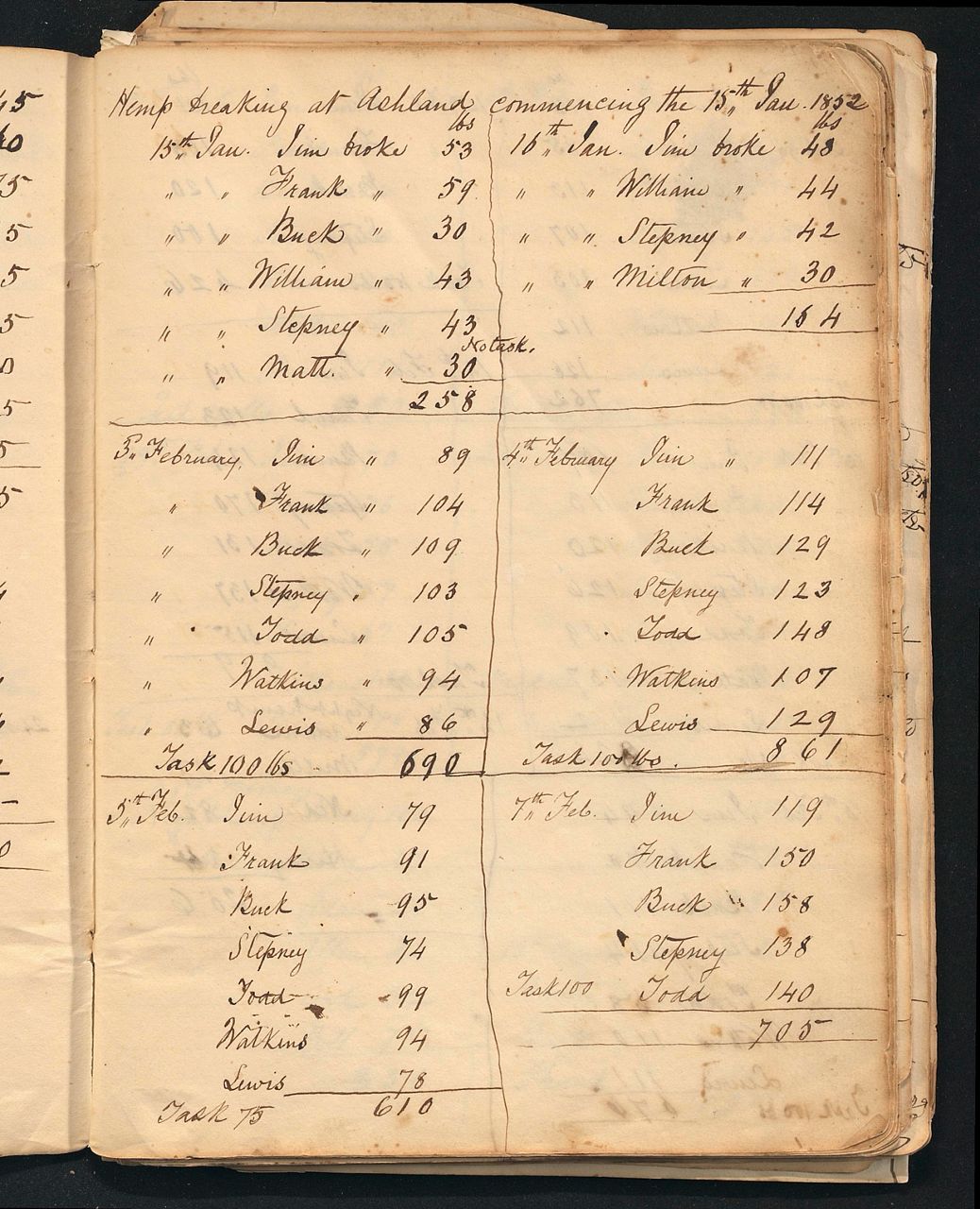

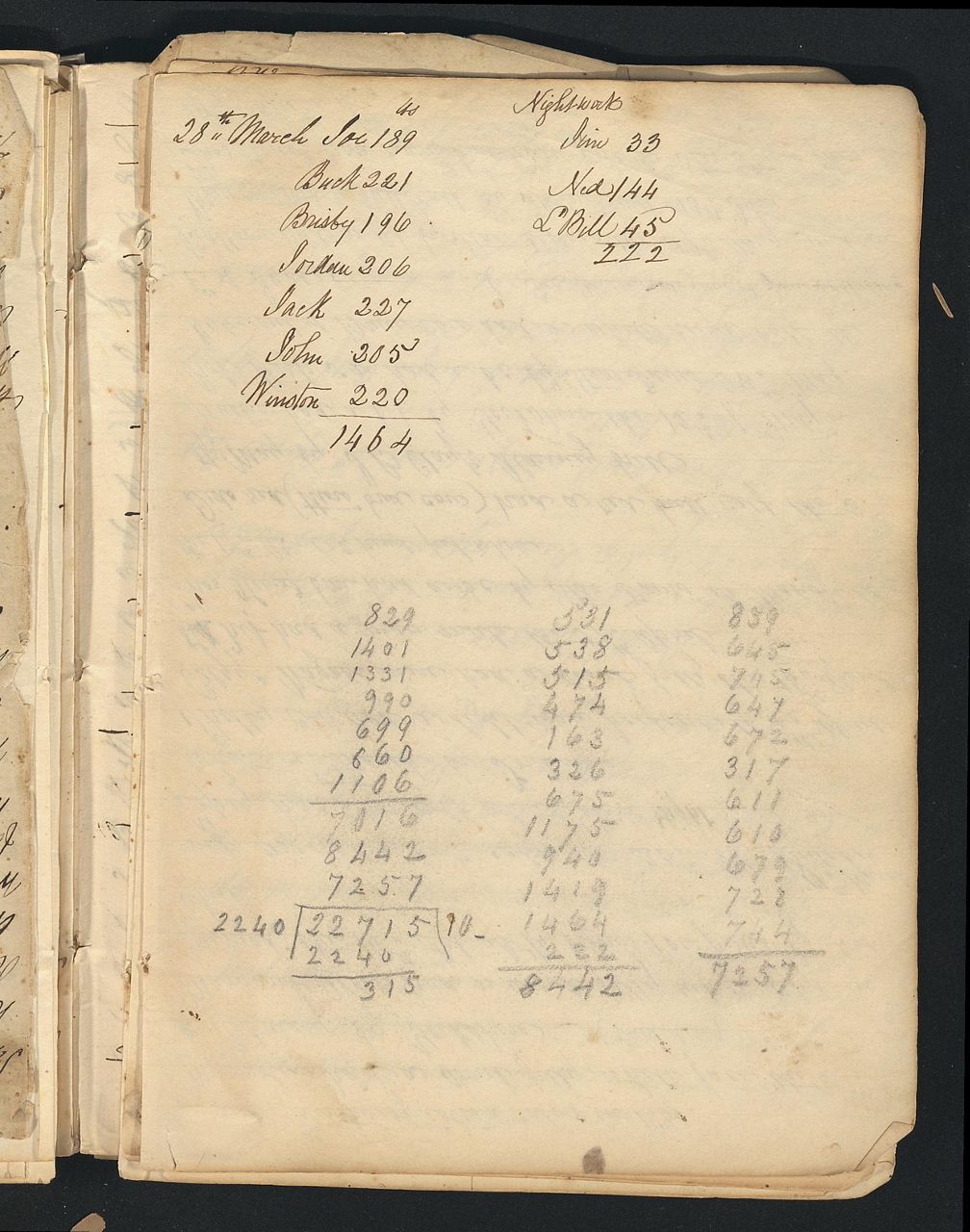

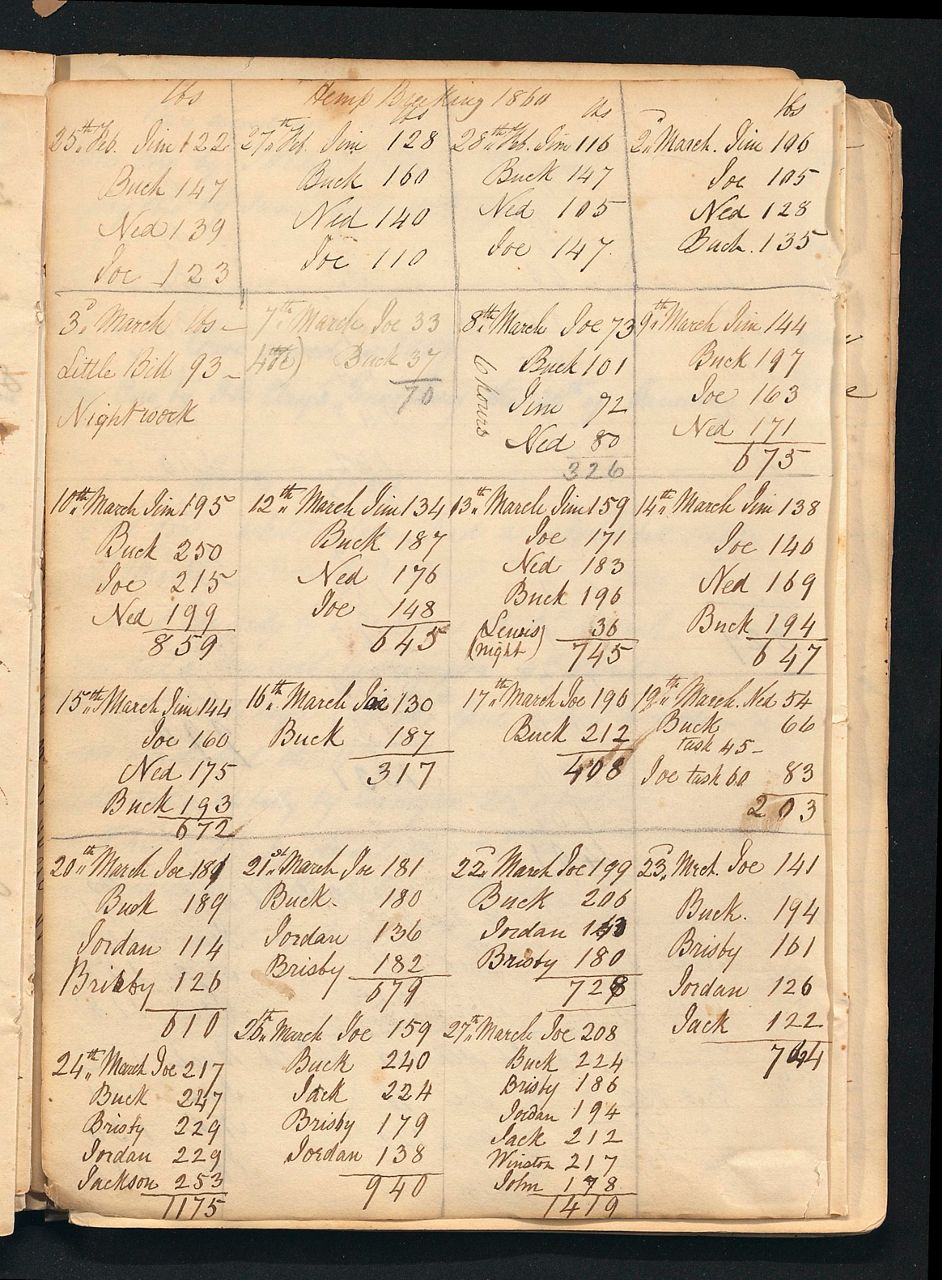

“Uplifting the historical figure of Henry Clay, but if you understand the timeline of his career and the agricultural innovations of Ashland, Mr. Clay was in Washington, D.C. for twenty-five years,” she said. “There were tons of innovations happening around hemp. We have to dial back and ask who were those hidden figures leading the charge, out in the fields, breaking the stalks?”

“When a lot of these innovations were being developed, Black people weren’t in a position to get patents for them,” said Claiborne.

In advocating against abolishing slavery, William Bullitt, a Kentucky delegate to the constitutional convention of 1849 pleaded to keep the institution alive to maintain the production of hemp. According to Hopkins, Bullitt said, “Take away slaves and you destroy the production of that valuable article.”

A recent investigation by The Atlantic outlined how even well after slavery ended, systemic discrimination “dispossessed 98% of Black agricultural landowners in America.” At least one group, Minorities for Medical Marijuana, is pushing for anti-discrimination language to be written into future federal hemp legislation.

“Not only written into law but it has to be enforced,” said Claiborne.

“But how are you going to enforce it? Who is going to make sure that it is enforced on the local level,” Smith said.

The 2018 Farm Bill includes $435 million over ten years that’s designated, in part, to training and outreach programs for underserved farmers.

Former University of Kentucky basketball star and retired tobacco executive, Merion Haskins, doesn’t share their concerns. In fact, the Greensburg farmer is reluctant to reflect too deeply on the historical context of hemp at all.

“Hopefully we’ve moved on,” said Haskins. “We all exited our family farms. We all got educated, went to universities. We got jobs with major corporations and then we left the farm,” he said.

“I have so much confidence because I was at the meeting in Louisville with Senator McConnell and Secretary Perdue and they promised us in 2020 that we would have our federal crop insurance,” said Haskins.

At the invitation of McConnell, United States Department of Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue visited hemp operations in Louisville and Lexington in July.

Regulators from the USDA, Food and Drug Administration and Environmental Protection Agency are working to come up with the rules for the hemp economy. The USDA isn’t expected to roll out a plan for hemp crop insurance until next year. Still, Haskins got involved because he says given Kentucky’s once-thriving tobacco economy, the infrastructure is ripe for hemp.

“I think it’s going to benefit everyone. We will be adding to the tax base. We will be employing people,” said Haskins.

For brother and sister, Paul Price and Jan Brazley in Hodgenville, it’s also about the dollars and cents.

“I am a retired school teacher who has taken up the profession of farming. I’m working harder now than I’ve ever worked in my life,” said Brazley.

While it saddens her that so many Black farmers have not been able to hold onto their property, she doesn’t view the work as something she wants to pass along to her children.

“We have started maybe a revolution. I don’t know and other people can see our story and be encouraged that they can do the same thing. I’ve committed for 5 years and after I’m out. I will be almost 70,” she said.

“For me personally, it was the money,” said Price.

A retired government contractor, he also describes this venture as primarily a business investment but because he’s a Black farmer, he says he feels a particular need to meticulously adhere to the evolving regulations.

“We are not blind to the fact that we are African American so there are things that we may not be able to get away with that others can,” said Price.

But that consciousness isn’t slowing him down. He’s already leaning on his sister to take an even bigger risk by growing a larger amount of hemp next year.

“We always put God in it. We are trusting in the Lord and we believe this is what he has for us to do at this time,” said Price.