LOUISVILLE, Ky. — “Since the escalation of racial tensions is one of the major problems facing our country today, it is most urgent that history books contribute to understanding between races.”

In 1971, that line appeared in the introduction to “Kentucky’s Black Heritage,” a book published by the Kentucky Commission on Human Rights (KCHR) to help teachers educate their students on the long tradition and vast contributions of Black Kentuckians.

A half-century later, the book and its mission remain relevant, said Terrance A. Sullivan, the Executive Director of KCHR.

“Teaching Black history is vital. True Black history, that it is,” he told Spectrum News 1. “We need to share more uncensored versions of our true history and create greater context for where we are today.”

This Black History Month, upon the 50th anniversary of the publication of “Kentucky’s Black Heritage," Spectrum News 1 looks back at one of the first attempts to provide large-scale education about Black Kentuckians to the commonwealth's children, how the book came to be, and the legacy it’s left.

In the fall of 1971, at an event held by the local Black-owned newspaper, The Louisville Defender, attendees were quizzed on their knowledge of local Black history. Dozens failed to correctly answer questions about the 1870 demonstrations in Louisville to integrate street cars, the Black Kentucky Derby-winning jockey Issac Murphy, and A.D. Porter Sr., a Black man who ran for mayor of Louisville in 1921.

The event was held to promote “Kentucky’s Black Heritage,” which had been recently published by the KCHR to “counteract the absence of knowledge about Kentucky Black history,” John A. Hardin, Professor Emeritus of History at Western Kentucky University, told Spectrum News 1.

The 162-page volume was conceived in the spring of 1970 following the Kentucky General Assembly’s passage of House Resolution 59, which directed state agencies to spread knowledge about state history. This came four years after Kentucky became the first state in the south to pass a civil rights law and six years after the landmark U.S. Civil Rights Act. By the summer of 1971, KCHR had printed 10,000 copies of the book with plans to distribute them to libraries and schools across the state.

“The history of Black Kentuckians has too long been ignored or misrepresented by general textbooks about Kentucky,” the book’s introduction reads. "Kentucky’s Black Heritage" was meant as a corrective, benefiting both white and Black students. The book had two “basic purposes,” the introduction says:

“1. To give black students knowledge of the role played by Black Kentuckians in the development of Kentucky so that they may possess a sense of pride in their heritage.

"2. To give young white students an accurate understanding of the problems faced by Blacks and of the creative role Black people have played in the state’s history.”

Hardin said the book arrived at moment when Black history education in Kentucky was largely confined to the pages of The Louisville Defender and The American Baptist, a newspaper of the General Association of Baptists. “Traditional media — daily newspapers and television stations — did not provide regular Black history education,” he said. “'Kentucky's Black Heritage' was a positive step forward because it compressed Kentucky Black history for use in the public schools.”

By the end of 1971, there was some evidence that the appeal was even broader than that. According to a Courier-Journal article published at the time, a “black market in Black history” became apparent when copies of the book were found for sale on street corners for $1.

“Kentucky’s Black Heritage” contains 23 chapters that begin with Kentucky’s first settlers in the 1770s and continue through the civil rights struggles of the late 1960s. The first Black person mentioned in the book is the man to whom it is dedicated. Whitney M. Young, Jr. is the Shelby County-born civil rights activist and social worker who died just months before the publishing of “Kentucky’s Black Heritage.” The book is dedicated to Young because, its authors write, “his life and deeds exemplify the brave and inspiring service of Kentucky’s Black citizens.”

The next Black people mentioned are nameless. There’s a “body servant” and a “woman belonging” to Colonel Richard Callaway. Both were among the earliest settlers in Kentucky. As was Cato Watts, identified as “Louisville’s first Black resident.” Watts was a musician who played the violin at Louisville's first Christmas party in 1778. The book, a text meant for children in schools, omits details of Watts's dramatic demise. He killed his owner, leading him to become the first person ever hanged in Louisville.

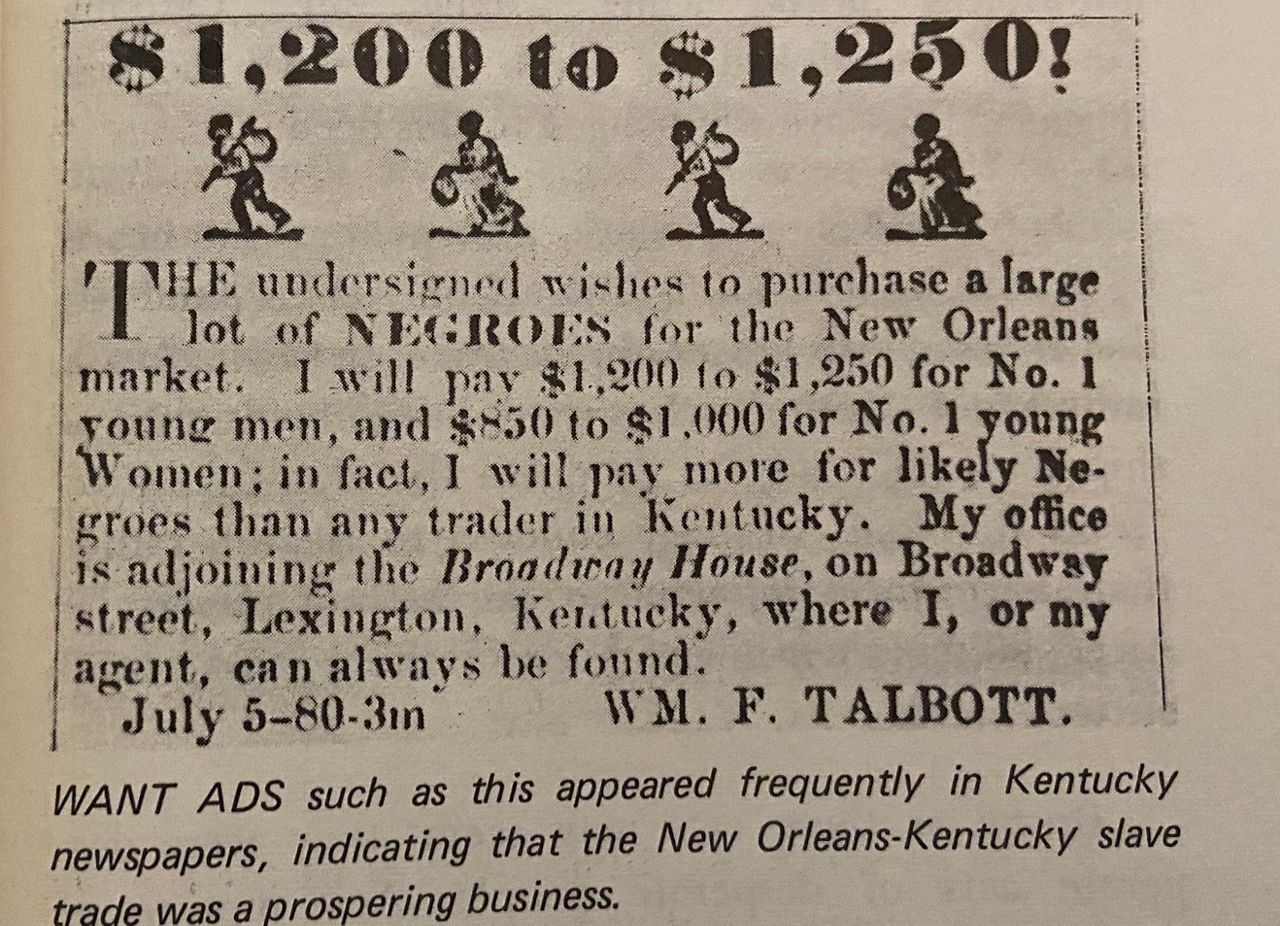

The book continues with sections dedicated to slavery, the Civil War, its aftermath, and the Civil Rights era. It doesn’t avoid the dark moments, with gruesome details about slave life and punishments by whipping and branding. But it also notes the early contributions of those who escaped slavery, such as Henry Bibb, who fled captivity in Oldham County, became an anti-slavery lecturer, and founded a colony for newly freed Blacks in Canada.

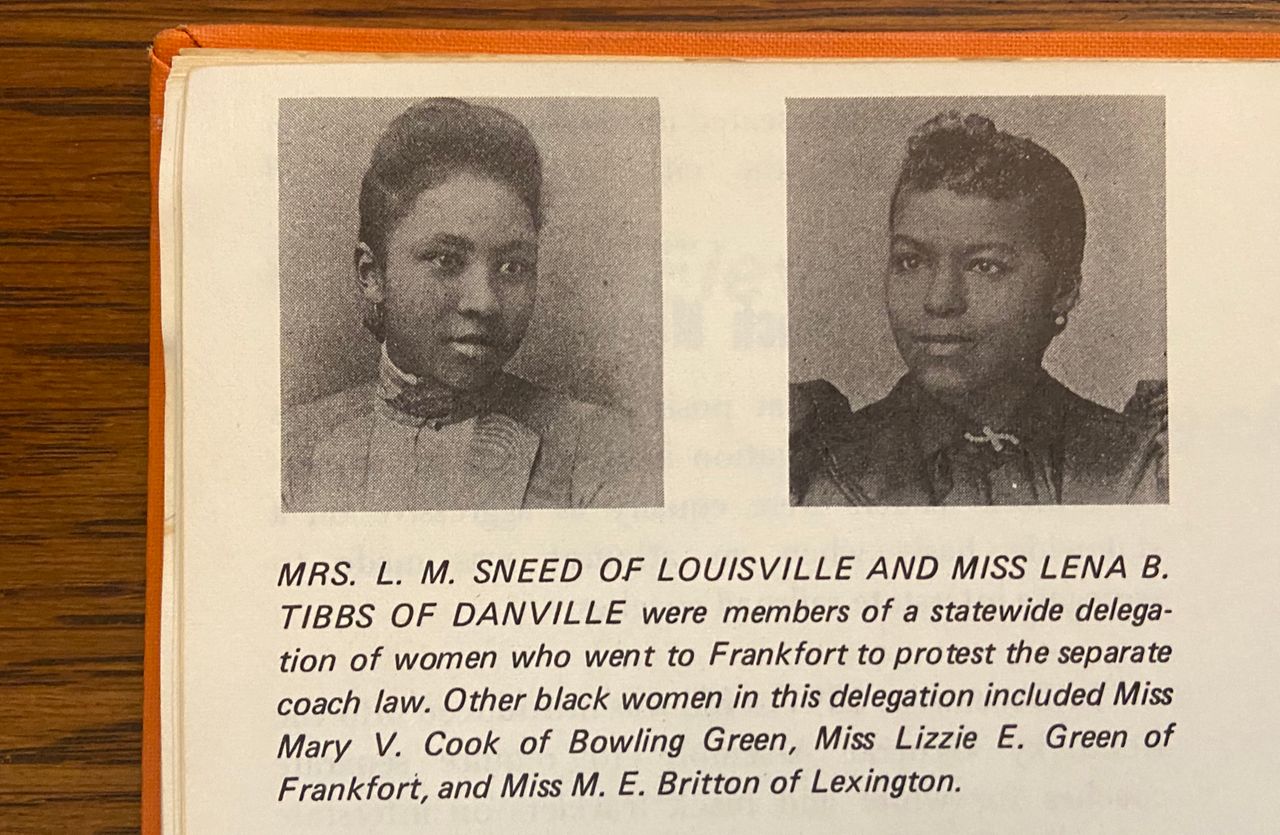

Sprinkled throughout the volume are primary sources showing ads placed by those seeking to purchase slaves, mugshots of white and Black coal miners who worked side-by-side organizing in Harlan, and a mural painted in the '60s showing Kentuckians fighting for Black liberation.

It tells of the sacrifices of Black soldiers during the Civil War, the continued violence against Blacks after the end of slavery, and early protest movements, such as an 1870 sit-in to protest segregation of Louisville’s streetcars. It also highlights Black success, such as the Mammoth Life and Accident Insurance Company, Kentucky’s largest Black-owned business, and the establishment by two Black doctors of the Red Cross hospital in downtown Louisville.

“Kentucky’s Black Heritage” ends with a summation of the civil unrest that took place in Kentucky prior to the book’s publication, and with it, more language that feels as if it could have been written today. “Black people of all ages organized to demand that society recognize the special problems they faced as Blacks,” while “some white citizens resent the Black mans’ re-emphasis on the goals of Black Power."

Black history education has come a long way in the half-century since the publication of “Kentucky’s Black Heritage,” in no small part due to the book's publication itself. Upon its release, Hardin said, the book became “the basic Kentucky Black history book for many people.” He credited the book as “a positive step forward because it compressed Kentucky Black history for use in the public schools.”

And supplements began arriving within years. Alice Allison Dunnigan’s “The Fascinating Story of Black Kentuckians: Their Heritage and Tradition” was published in 1982. “The History of Blacks in Kentucky,” by Marion Brunson Lucas and George C. Wright, came in 1992.

Around the same time, Hardin announced plans to update “Kentucky’s Black Heritage” with information on the 1970s and 1980s. He wanted to discuss housing, economics, and segregation in higher education. He also wanted to add information about writers, artists, and other Black contributors to Kentucky’s cultural.

“It’s very easy to talk about basketball players from Lexington and Louisville,” he told the Lexington Herald Leader in 1994, “but there are others.”

Hardin's efforts took longer than initially expected and eventually morphed into something else. In 2015, the University of Kentucky press published “The Kentucky African American Encyclopedia,” a 624-page book with 1,500 entries and more than 150 writers. Hardin was one of three general co-editors.

Books like his are part of the current landscape of Kentucky’s Black history education, which is is still evolving. Just last summer, the largest school district in the state, Jefferson County Public Schools, announced plans to update its Black history curriculum to reflect content that "is both historically and contemporarily important to people of color.”

Sullivan said efforts like this are still necessary in a state with a history of “tremendous Black leaders” who are often overlooked. Not only does a deeper, more accurate portrayal of Black history tell us about who we are, he said, but it’s a small part of fighting the discrimination many Black Kentuckians still endure.

“This is not the only or best way to fight discrimination, but it does help go towards understanding," he said. "Understanding where people are coming from, and their history, is a building block in the foundation, but it is not the main structure. We need to teach history accurately, but we also need to do other and larger pieces in our fight against discrimination."

To learn more about Black History Month in Kentucky, visit our special section.