GEORGETOWN, Ky. – It was nearly 46 years ago when a standout athlete from Georgetown High School became the first Black player on the University of Kentucky women’s basketball team.

Lillian Nareen White-Washington, 65, enrolled at UK in the fall of 1975 after graduating from Georgetown High School – the last class to be graduated before the school was absorbed by Scott County High School. Her path to the present day has been long and, she admits, sometimes complicated, but her athletic ability, not the color of her skin, is what cemented her place in the storybook of Kentucky sports.

What You Need To Know

- Nareen White-Washington was a standout athlete in track and basketball at Georgetown High School

- Chose to play basketball at UK over running track at Tennessee State

- Later transferred to Eastern Kentucky University before enlisting in the U.S. Army

- Lives in Georgetown and is a foster grandmother for children with disabilities

White-Washington began her foray into Kentucky athletics lore her seventh-grade year after joining the Buffaloes’ track team. She proceeded to go undefeated in her best event, the 800-meter race, through her senior year and still holds the high school record in Scott County with a time of 2:23.5. She won all her running events at the state tournament from her eighth-through eleventh-grade years; a pulled hamstring kept her out of state competition her senior year. She also competed multiple times in the long jump at the state tournament.

“I never knew where I stood as far as being an athlete or a runner, I just ran,” she said. “I didn’t know I was one of the best runners in the history of the school – I just didn’t think like that and no one talked about it.”

White-Washington trained during the summers with the Kiwanis Track and Field Club in Lexington under coaches Sandy Perkins and Barbara Jean Call, an affiliation that would later be a factor in a major life decision.

White-Washington idolized Black female athletes such as world-record-holding and three-time Olympic gold-medal-winning sprinter Wilma Rudolph and tennis player Althea Gibson. She briefly considered running track at Rudolph’s alma mater, Tennessee State, for legendary coach Ed Temple, but chose not to when she was told she could not play basketball as well.

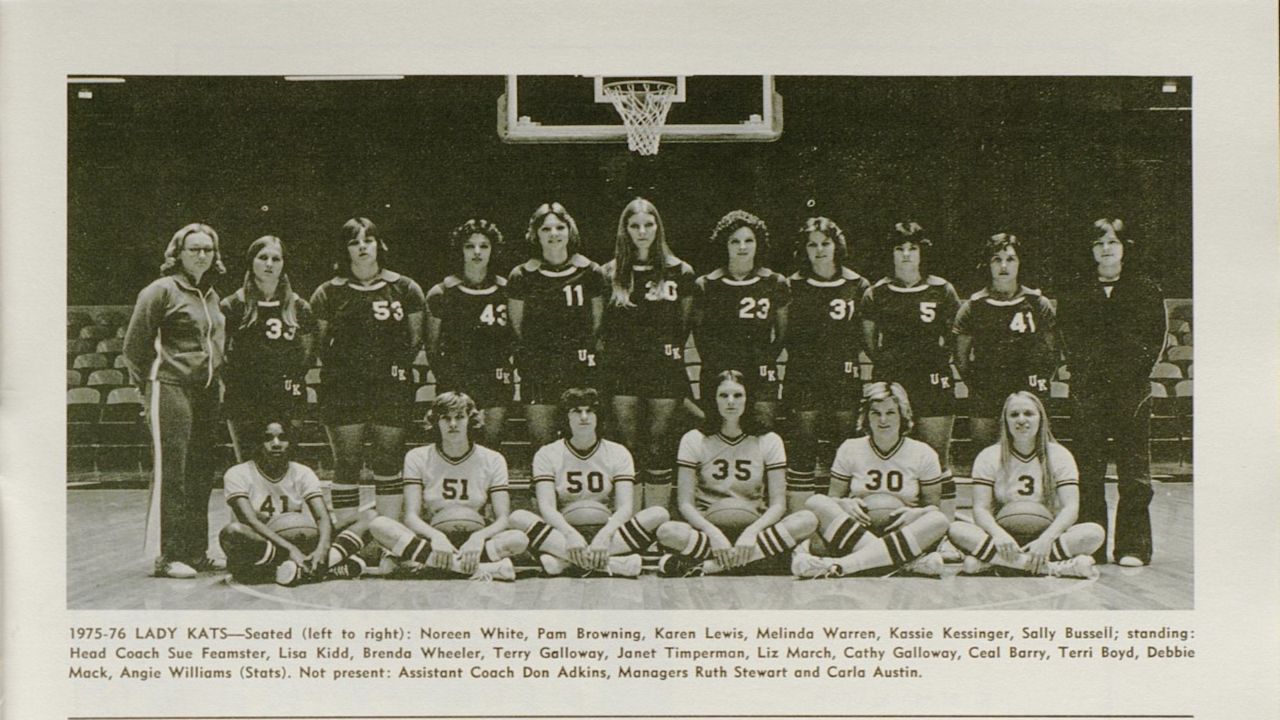

White-Washington started playing organized basketball her junior year when Georgetown High School added girls’ sports. Even at just 5-feet 4-inches tall, she excelled at basketball, being named a Kentucky West All-Star and ultimately earning a scholarship offer from then Head Coach Sue Feamster to play for the Wildcats.

White-Washington was a force on defense for the Wildcats and garnered ample playing time as guard and forward coming off the bench as a freshman.

“To be honest, I felt like I was always on the back burner,” she said. “I competed with a lot of other athletes that were always mentioned, and were stars, and I just couldn’t understand that because — and I’m not bragging — I knew I could outplay a lot of them.”

White-Washington was a force on defense. She said she spent most of her time working to become a better rebounder because she felt as a freshman, her job as a role player coming off the bench was to get the ball to the older white players on the team.

“I felt like I was part of the invention of the role player,” she said. “It also was clear that good role players can help teams win ball games.”

White-Washington credited her defensive prowess to speed and footwork, two things she had inadvertently been working on for years.

“That had a lot to do with running track,” she said. “As an athlete, it helped me to be able to accomplish things that the other girls couldn’t – I know I had an advantage because, by running track, you're strengthening your legs, and strengthening your legs, helps you leap.”

White-Washington did not feel as if she was treated poorly or differently while at UK because she is Black, saying she did not understand a lot of things because she had not seen a lot of things and therefore did not know a lot of things.

“I didn’t even really know I was Black,” she said. “I was just Noreen White (Washington), a little girl who wanted to play basketball and I just didn’t think about things other than that. But I could feel it. I started feeling things and picking up on things, and that was out of the norm for me because, at home in Georgetown, I had my coaches and my parents. Georgetown was the type of community where we didn’t see a lot of things. Coach Feimster kept me in like a bubble and kept a lot of things away from me. She was a good person.”

In the spring of 1977, White-Washington was selected to travel to the University of Tennessee in Knoxville for a chance to be an alternate on the U.S. Women’s Olympic Basketball Team coached by the late Pat Summit. She did not make the team, but said she learned a lot about herself as a basketball player.

“That was quite an experience,” White-Washington said. “There were players from all over the country coming in there to try out and they let me know where I stood, and the areas where I could improve and be a better basketball player.”

Playing basketball at UK, it turns out, was the easy part for White-Washington. After returning to Lexington from Knoxville, White-Washington learned from Feamster that she had been placed on academic probation.

“I was too embarrassed to tell anyone about my academic problems and probation,” she said. “I was the only person of color that was there, and I so deeply wanted to make it, to accomplish great things, but UK was foreign to me. I never really learned how to study. There were times when I would forget where my class was. The most embarrassing thing was I went to a lecture class and didn't understand anything, so I raised my hand. The professor asked me to come down after class and told me to never raise my hand in lecture class again, that if I want to know something I had to come to the lab. I said, ‘What's the lab?’ I didn’t even realize I had it on my schedule. I really struggled. How was I going to tell my mom that I am not as smart as the other girls? I started thinking to myself that I wish I would have taken a college English class so I would know how to write a paper. I wish I would have studied more. There are so many things I wish I could go back and do to prepare myself. Going to UK was a really big step for a little country girl.”

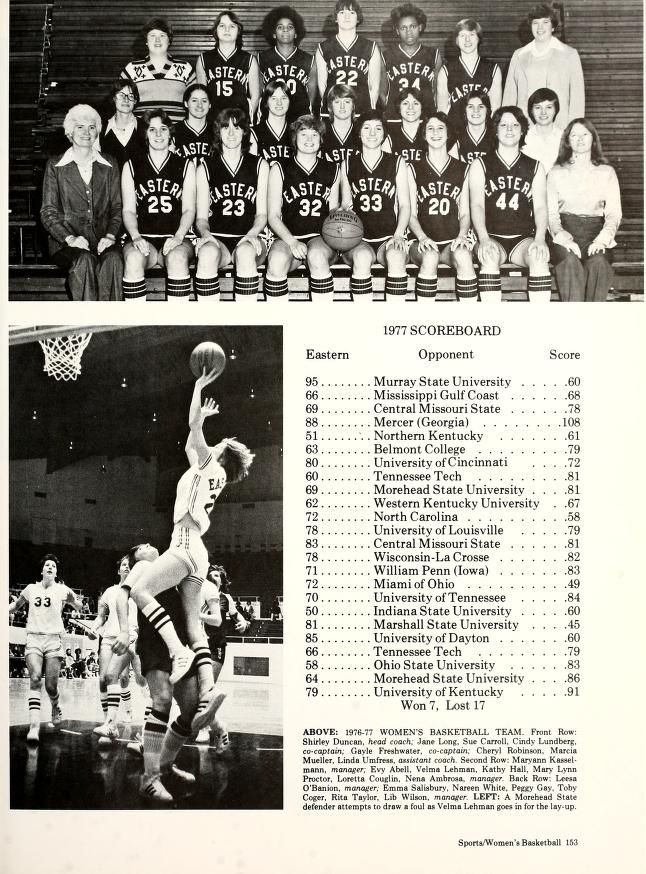

White-Washington sat out for a semester after being placed on academic probation before making the decision to leave UK in the spring of 1977 and transfer to Eastern Kentucky University, where she was given a partial track scholarship and played basketball as a walk-on. Her arrival at EKU marked White-Washington's second time being the lone Black player on a women’s college basketball team.

“It was pretty much the same way there,” she said. “I was the only Black girl on the team when I got there.”

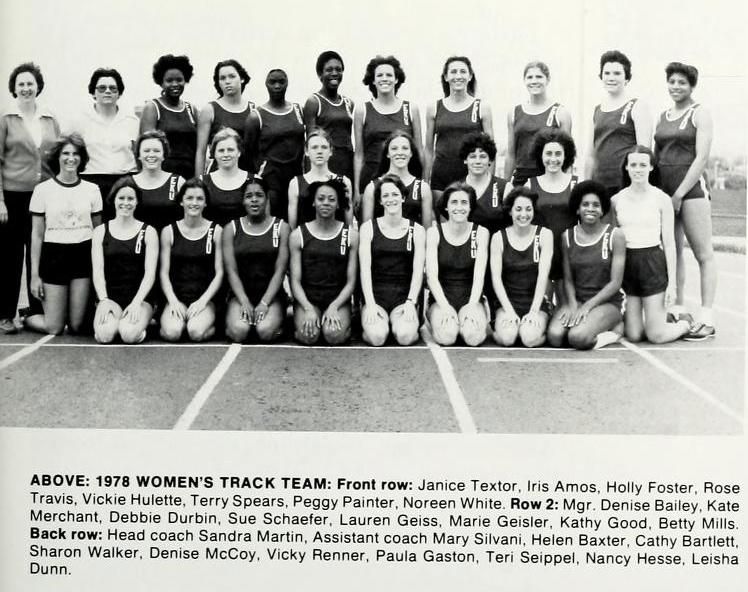

While running track for EKU Hall of Fame coach Sandy Martin and Perkins, her summer team track coach and an assistant at EKU, White-Washington was one of the top runners in the Ohio Valley Conference in the mile-relay and cross country events, and a rival of Anita Jones at Western Kentucky University.

“Those were the beautiful days,” White-Washington said.

She remained at EKU until the end of the 1980 spring semester. When it looked as though she was not going to earn the required credits to graduate from EKU, she made another major decision.

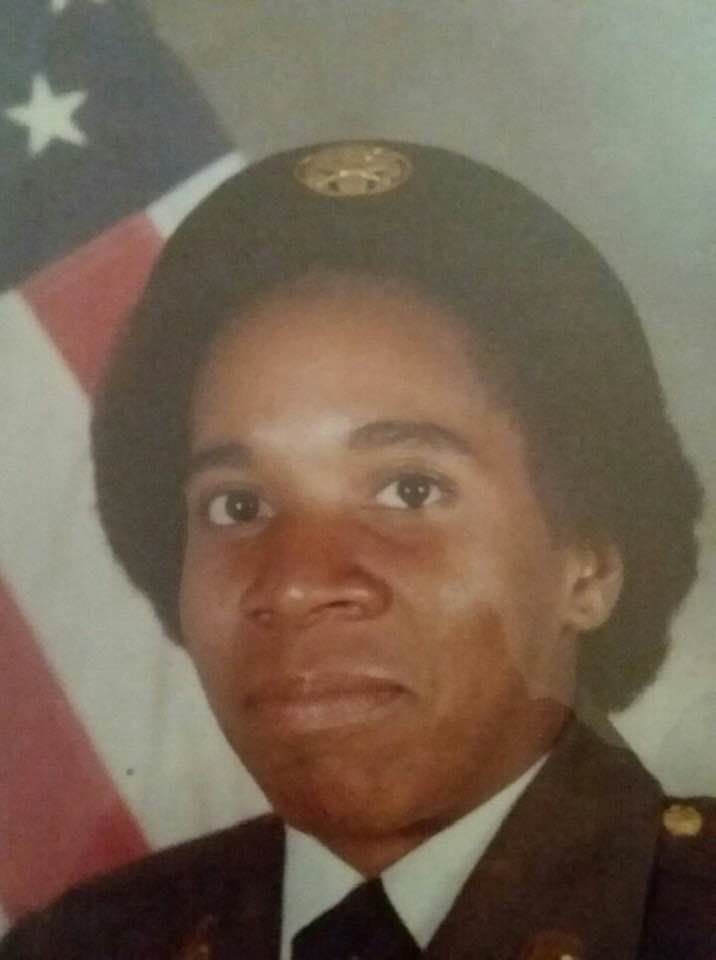

While still in Richmond, White-Washington enlisted in the U.S. Army.

“I knew I couldn’t go home and tell my parents I wasn’t going to graduate,” she said. “I thought I had better get out of there for a while, so I went to the local recruiting office and signed up to join the Army. The track team was supposed to compete at the national competition the day I enlisted. When I told my teammates I couldn’t go to nationals they thought I was joking.”

She played basketball while enlisted, even meeting her first husband while doing so, and although she admits she loved her time in the Army, she said it took her years to begin recovering from some of her experiences.

“I just couldn’t focus. I couldn’t jump start. I couldn’t even reset myself,” she said. “After years and years, I realized I need to talk to somebody – I need therapy. I had a friend tell me that if I didn’t go get the therapy, I was going to kill myself or somebody.”

When White-Washington went to the VA hospital for tests, she was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). She said if not for therapy, she doubts she would have ever talked to anyone about what happened to her in the Army.

“The VA put me in the Wounded Warrior program, but I didn't like,” she said. “I was learning about others and what they're going through and I couldn’t handle it at that time.”

White-Washington, a mother of three and grandmother of one, worked for the Lexington Parks and Recreation Department and worked with Jackie French, who supervised the Dirt Bowl Basketball Tournaments. White-Washington and French were the only two women to coach basketball for the city and had the top two teams in the children’s inner city league.

Outside of work, White-Washington also stayed active, participating in races such as the Bluegrass 10,000, and after a few years working in Lexington, she went to work for the city of Georgetown, from where she retired after 15 years.

White-Washington has volunteered for the Community Action Foster Grandmother Program for the past 10 years. She was awarded a Trailblazer Award by Bluegrass Black Pride Inc. in 2018 and will be recognized by UK for being the school’s first Black women’s basketball player in a ceremony set for Thursday, Feb. 11, as part of Black History Month events.

For more information about Black History month, please visit our special section.