California has experienced devastating and historic fire activity over the past two years. In fact, there have been roughly 15,800 fires statewide since 2020, while the five-year average from Jan. 1 to mid-September is 6,900 fires. Nearly six million acres have burned since 2020, or six times the average acreage over a five-year period.

What exactly is going on? Are warmer temperatures to blame? The drought? While available fuels and weather conditions control the potential for large wildfires, ultimately, it comes down to ignition.

How do wildfires in California most often start? The answer is not lightning, which accounts for just 12 percent of wildfire ignitions globally, but far fewer ignitions in California. The real problem is human-caused ignitions—whether accidental or intentional—which account for 88 percent of ignitions globally, but are closer to 90 to 95 percent of ignitions in California.

The top ignition causes are:

- Unattended campfires

- Equipment use or malfunction, including lawnmowers, tractors, trucks and power lines

- Burning of debris

- Fireworks

- Carelessly throwing out cigarettes

- Car fires or blown tires

- Arson

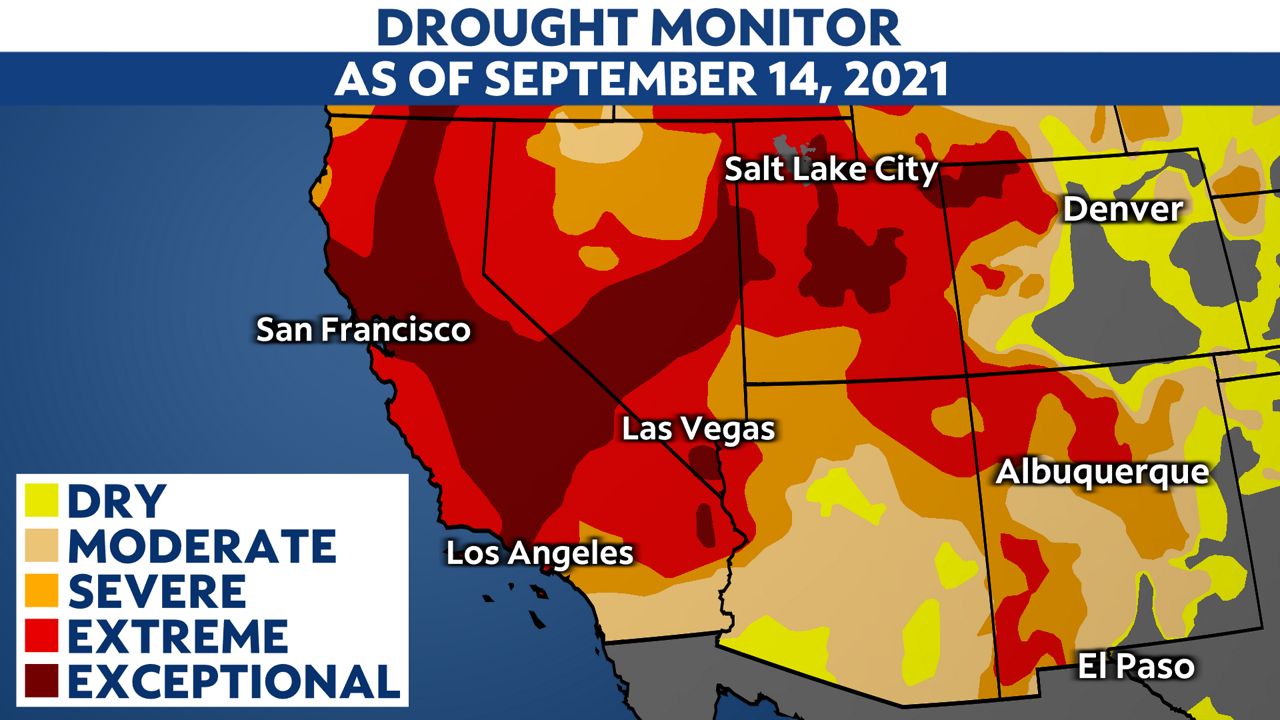

Here’s why we can’t afford to be negligent: Fuel moisture in grasses, shrubs, and trees, is running at historically low levels in parts of the state, thanks to two straight years of dismal winter rainfall. Most of the state is in exceptional drought.

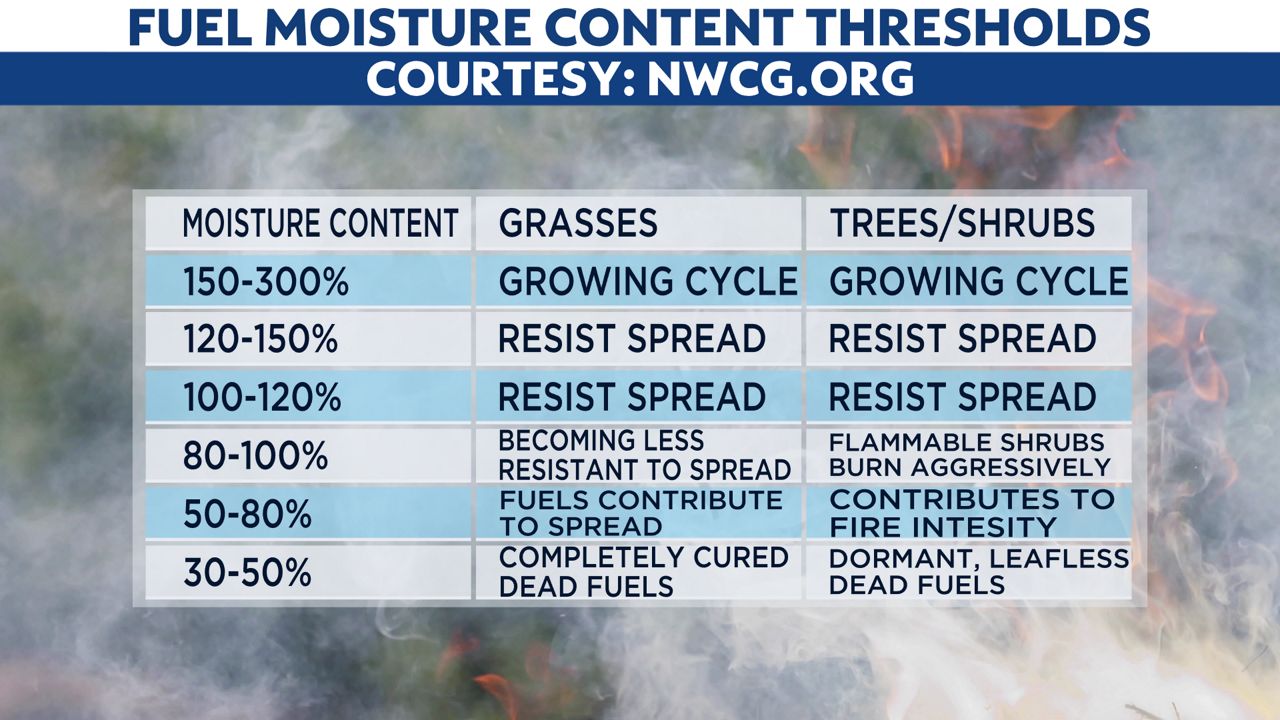

Why is this important? Because fuels that lack moisture will ignite more easily. During the summer and fall months in California, after a prolonged stretch without rain, fuel moisture content usually drops to 60 percent. Now with prolonged drought, fuel moisture content is currently as low as 40 percent in parts of Southern California.

Any fuel moisture content below 100 percent means the fuel becomes less resistant to ignition and anything below 80 percent will contribute to fire spread.

This is why you hear so much talk about “defensible space.” If you keep fuels around your house robust with moisture—say, around 100 percent fuel-moisture content—they will be far more resistant to ignition, even under the intense heat of a nearby or approaching wildfire.

The biggest risk is in mountainous terrain, as well as wildland-urban interface regions—foothill communities that sit on or near wildland vegetation in between mountainous terrain and more urban areas. These regions are quite literally in the line of fire.

New housing in wildland-urban interface regions has skyrocketed in the past 30 years, nearly doubling nationwide. Approximately one in three houses is in the interface. Half of all building losses in California wildfires are located in the interface, despite only accounting for two percent of acreage burned.

The risk is two-fold: With more people in the interface, there is a greater chance of wildfire ignition and with more homes in the interface, there is a greater risk to life and property.

Areas that are in the wildland-urban interface and have not been touched by wildfire in the past 20 years are most at risk, especially if fuel moisture is at critically low levels.

Wildfires in California are almost always started by human negligence. With drought becoming more of a mainstay in California climatology and with more people than ever before residing in high-risk wildland-urban interface regions, it is critical we remain vigilant and do our part to prevent fire ignition and spread.