LOS ANGELES — Long-suffering California Republicans will see something on the March ballot that might shock them: a U.S. Senate candidate whose name they recognize.

The state's Republican Party has been in a decades-long tailspin in heavily Democratic California, where a GOP candidate hasn’t won a U.S. Senate race since 1988 and registered Democrats outnumber Republican voters by a staggering 2-to-1 margin.

What You Need To Know

- As a Republican, the one-time National League MVP and perennial All-Star who also played for the San Diego Padres remains a long shot to fill the Senate seat long held by the late Democratic Sen. Dianne Feinstein

- Republicans have struggled for years to enlist viable candidates for marquee offices

- Garvey is competing in a field that includes three Democrats with high profiles in Congress — Reps. Barbara Lee, Katie Porter, and Adam Schiff

- Mail ballots go out to voters early next month

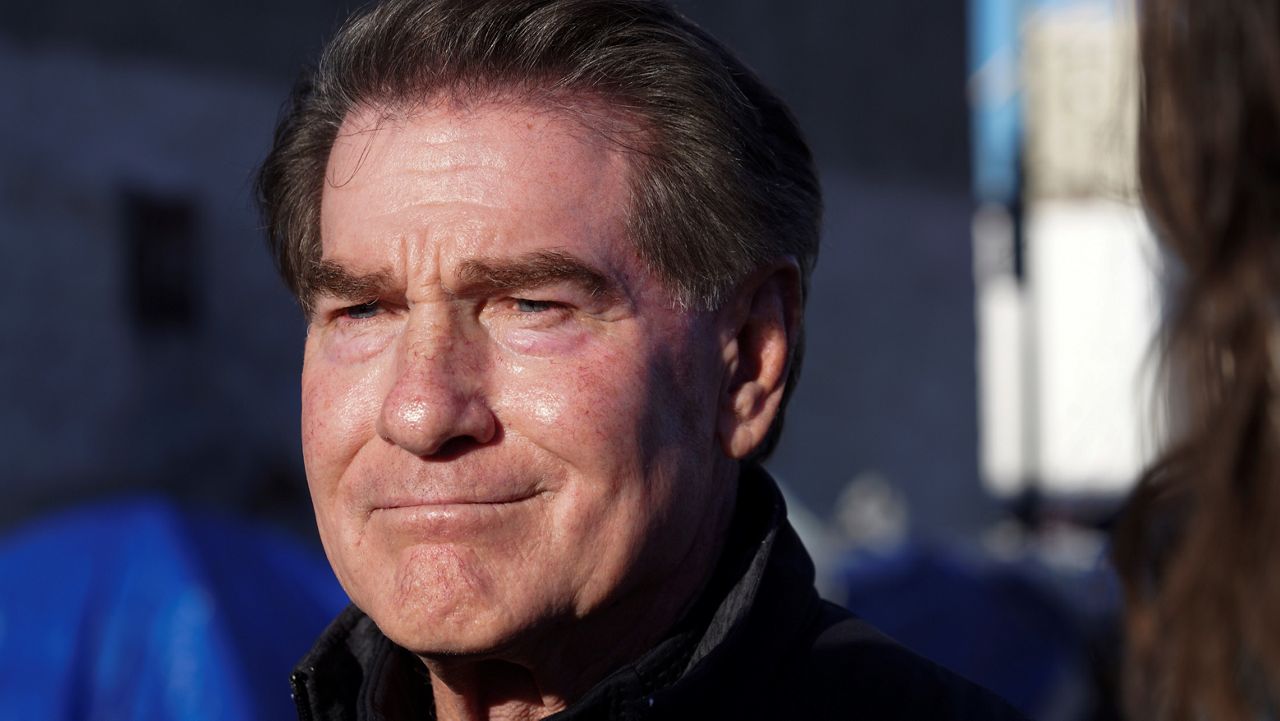

This year, the candidacy of former Los Angeles Dodgers star Steve Garvey has brought a dash of celebrity to the race that has unsettled his Democratic rivals and tugged at the state’s political gravity.

As a Republican, the one-time National League MVP and perennial All-Star who also played for the San Diego Padres remains a long shot to fill the Senate seat long held by the late Democratic Sen. Dianne Feinstein. But it’s also possible he could emerge as one of two candidates from a crowded March 5 primary election to advance to a November match-up.

Under California rules, Democrats and Republicans appear on the same primary ballot and the two candidates with the most votes advance to the general election, regardless of political party. Republicans have struggled for years to enlist viable candidates for marquee offices — voters could choose from only two Democrats for Senate in the 2016 and 2018 general elections.

Since Garvey is competing in a field that includes three Democrats with high profiles in Congress — Reps. Barbara Lee, Katie Porter, and Adam Schiff — the primary math could work in his favor if Republican voters unite behind him. Even getting to November would be a small victory, if likely only a symbolic one.

“People know me. I played in front of millions of people,” Garvey said during a recent stop in downtown Los Angeles, referring to his 18-year major league career.

In a state that has witnessed a long-running homeless crisis, seven-figure home prices, a declining population and a rash of smash-and-grab robberies, what California needs is “a fresh voice, fresh ideas,” Garvey said. “We need to bring back the vibrance of California.”

Mail ballots go out to voters early next month.

In his first run for office, Garvey is hoping to follow a pathway cut by other famous athletes-turned-politicians that includes former California Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, a one-time bodybuilder and actor who became the last Republican to hold the job, Utah Rep. Burgess Owens, a former NFL player, and former professional basketball great Bill Bradley, who became a long-serving U.S. senator in New Jersey.

So far, Garvey has gotten off to a bumpy start.

After entering the race in October, the political novice who calls himself a “conservative moderate” is still attempting to define what that label means. He has said he should not be buttonholed into conventional labels, such as former President Donald Trump’s Make America Great Again political movement.

Garvey has twice voted for Trump, who lost California in landslides but remains popular among GOP voters, but he has said he hasn’t made up his mind about this year’s presidential contest. He personally opposes abortion rights but does not support a nationwide abortion ban and will “always uphold the voice of the people,” alluding to the state’s longstanding tilt in favor of abortion rights.

Those positions made him a frequent target Monday in a televised debate, where his Democratic opponents ridiculed him as callow and evasive.

“Once a Dodger, always a dodger,” Porter quipped after Garvey again evaded the question about whether he'd support Trump this year.

“This is not the minor leagues,” she scolded. “Who will you vote for?”

If many of Garvey’s answers lacked specifics, he did succeed in presenting himself as a Republican alternative to three Democrats who are largely indistinguishable on policy matters.

At the Los Angeles appearance, he acknowledged that as an outsider he doesn’t have experience to match career politicians but said he was a “fast learner.”

Garvey will have a hard time winning over voters like Los Angeles writer Tosh Berman, a Democrat who is leaning toward Porter. He recalls Garvey as a glamourous figure in his playing days in the 1970s and '80s, whose lantern-jawed visage was a fixture in the media at the time.

While an outsider can sometimes bring a fresh look at problems, Berman is not convinced in this case. Members of Congress need to know how to “play the game” to be effective, he said.

“A politician should be a politician,” Berman added, standing outside a library in the city’s Silver Lake section. “It’s a profession.”

Garvey’s challenge is first consolidating the GOP base – he’s dueling for Republican votes with attorney Eric Early, who previously has run unsuccessfully for state attorney general and Congress.

Garvey’s campaign believes that a key constituency will be the state’s most reliable voters: older, more affluent, white homeowners who probably remember him from his baseball days. Garvey knows he is probably a cypher to many younger Californians but believes he can connect with them because many of the same issues cut through generations, like high taxes, hefty prices at gas pumps and grocery stores or crime rates.

It's not yet clear how the nation's unsettled political climate will play out in California elections. Recent polling has found many Californians believe the state is headed in the wrong direction and see tough economic times ahead.

State Republican Party Chairwoman Jessica Millan Patterson has predicted that Garvey will surprise the Democratic establishment. California voters “are ready for change,” she tweeted.

Garvey already has seen attacks on his character tied to 1980s sex scandals that sullied his reputation as “Mr. Clean,” a moniker that referred to his buttoned-down image from his Dodger days. At the time he admitted to having two children with women he wasn’t married to.

He has said of those days, “I think our life is a journey. … I’ve gone through a difficult time here and there. I’ve learned from it.”

Now 75, his hair flecked with gray, Garvey moves slower than in his baseball heyday charging down the base paths. As he walked past weather-beaten tents and barking pit bulls on a visit to homeless encampments in LA’s notorious Skid Row section, he said he would bring compassion and consensus to the Senate but offered no specific plans to deal with an unsheltered population that has continued to grow despite billions in spending.

“This isn’t something we can neglect,” he said.