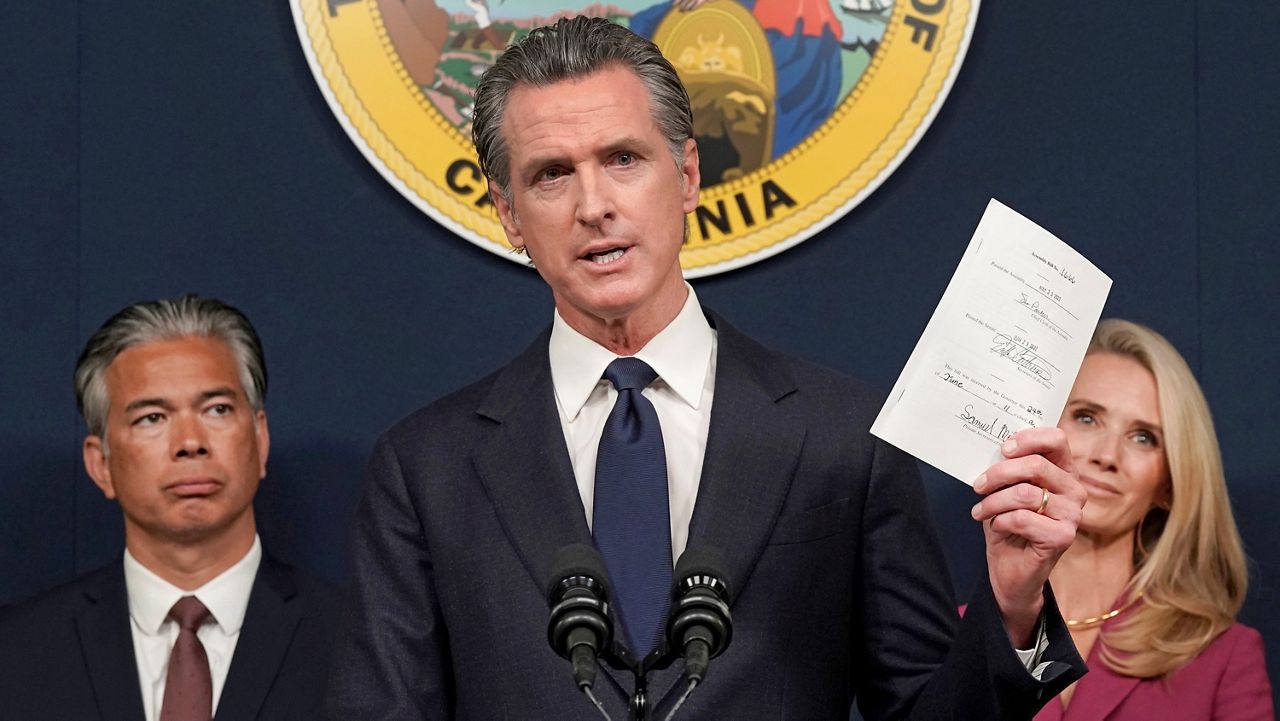

SACRAMENTO, Calif. (AP) — A first-in-the-nation bill to punish oil companies for profiting from price spikes at the pump breezed through the California Senate on Thursday at the urging of Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom, the first major vote in an effort to pass the law by month's end.

The proposal is in response to sales last summer, when the average price of a gallon of gasoline in California soared to a record high $6.48. Drivers in some places paid as much as $8 per gallon, prompting widespread outrage in an election year.

Newsom, a Democrat, reacted by attacking the oil industry, specifically the five companies that provide 97% of gasoline in the state. He asked the Democratic-controlled state Legislature to pass a new tax on oil company profits, arguing it would protect consumers by preventing price spikes.

That idea went nowhere in the Legislature, as lawmakers feared it would create chaos in the petroleum market and cause companies to make less gasoline, thus increasing prices.

Instead, lawmakers and Newsom settled on a bill that would let the California Energy Commission decide whether to impose civil penalties on oil companies for price gouging. The commission — a five-member panel appointed by the governor with the consent of the Senate — would rely on information from a new state agency that would have the power to monitor the market, including forcing companies to disclose financial information and having the power to subpoena oil executives to testify.

In 10 years, the bill requires the state auditor to investigate the program to find out if it is working to reduce gas prices. If it’s not, the auditor can order the program to shut down — but lawmakers will have six months to review that decision and reverse it if they choose.

“It is our role to protect our residents from any practices of any business that may harm them,” said state Sen. Nancy Skinner, a Democrat from Berkeley and the author of the bill.

The bill highlights the challenges of balancing the competing pressures of protecting consumers at the pump while at the same time pushing policies to end the state’s reliance on fossil fuels. California’s climate strategy — which includes banning the sale of most new gas-powered cars by 2035 — would reduce demand for gasoline by 94% by 2045.

“There are consequences for doing what we are doing, and (high gas prices) are one of the consequences,” said state Sen. Kelly Seyarto, a Republican from Murrieta who opposes the bill.

California’s gasoline prices are already higher than most other states because of taxes, fees and environmental regulations. California’s gas tax is the second-highest in the country at 54 cents per gallon. And the state requires oil companies make a special blend of gasoline to sell in California that is better for the environment but is more expensive to produce.

Republicans on Thursday tried to force a vote on a separate bill that would suspend the state's gas tax and some gas-related regulations for one year. But Democrats voted not to bring the bill up for debate.

At one point during the price spike last year, the average price of a gallon of gasoline in California was more than $2.60 higher than the national average — a difference regulators say is too large to be explained by taxes, fees and regulations.

Much of the oil industry’s complaints about the bill have focused less on the potential penalty and more on a new, independent state agency lawmakers would create to investigate the market. Oil companies would be required to disclose massive amounts of data to this agency, giving regulators a better sense of what could be driving price spikes. And, crucially, the agency would have subpoena power to compel oil company executives to testify.

Kevin Slagle, spokesperson for the Western States Petroleum Association, said oil companies would have to report data on 15,000 transactions per day, what he called “a ridiculous level of reporting” that would drive up costs. He said the real problem with California’s gas prices are state laws and regulations that hinder the supply of fuel. He criticized Newsom and lawmakers for rushing the bill through the Legislature with little input from the oil industry.

“Why does the governor want to jam this through? Clearly it’s because the details of this are not good for California consumers,” Slagle said. “They don’t address the problem, but it provides him a political win.”

Dana Williamson, Newsom’s chief of staff, said she has repeatedly had meetings with representatives from the oil industry to discuss the bill, including meetings with specific companies and two meetings with the Western States Petroleum Association.

“It’s a ridiculous over exaggeration that they have been cut out,” Williamson said.