YORBA LINDA, Calif. — Dressed in bright yellow and surrounded by men in dark suits and skinny ties, correspondent Vera Glaser asked her question, 37 words, that forced sitting President Richard M. Nixon to admit an error.

Glaser had asked why just three of about 200 government appointments had been filled by women, and if, in their minority, they would remain “the lost sex.” Surrounding men laughed before Nixon said he’d been unaware of the oversight and such a thing should be fixed.

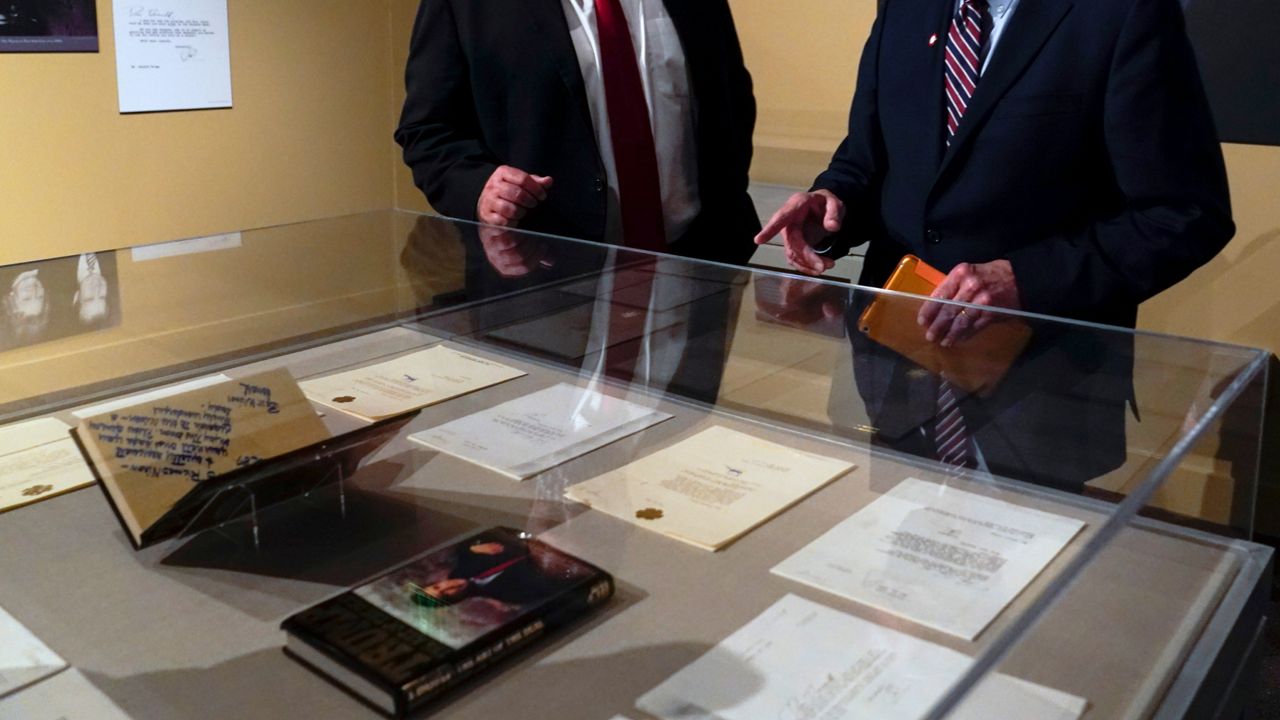

On Thursday, the Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum in Yorba Linda celebrated the 50th anniversary of Title IX, applauding Glaser’s question. The opening remarks of the celebratory lunch referred to the journalist’s query as the “37 words that changed everything.”

It was the start of what would become a rapid transformation in American government and education, speeding forth the participation of women through the landmark Title IX legislation, most often associated with girls’ and women’s participation in sports.

“I have to say, not everybody thought this was a good idea,” said Barbara Hackman Franklin, a staff assistant to Nixon, pivotal in creating a talent bank of women ready to compete for openings in middle management, even the Supreme Court and the highest levels of the military.

She was in attendance, herself wearing a yellow jacket, the color not unlike the one worn by Glaser, speaking about her experiences now recorded in the book, “A Matter of Simple Justice,” by Lee Stout.

Franklin herself would serve five presidents and become Secretary of Commerce under President George H. W. Bush.

But Nixon, who would later resign over the Watergate scandal, committed to the task and pushed for fast results.

In 1971, fewer than 300,000 girls participated in sports at the high school level, just 8% percent of the number of boys. Just a few years before that, about 15,000 women participated in college sports, or 10% of the number of men.

Once Title IX was passed on June 23, 1972, women and girls flooded into athletics with a 178% increase the next year. It continued with more than a 100% increase each of the following six years.

After Glaser asked her question, Nixon’s White House Task Force on Women’s Rights came up with a number of programs, including Title IX and Franklin’s task of headhunting for outstanding women to fill government jobs.

But the movement was more than about sports. It was about building a sustainable pipeline of qualified women to all kinds of government posts. Franklin built a network of friends in government who could help her identify when there might be a new job opening, making it easier for her to figure out what qualifications to look for. And then there was the issue of finding candidates. Many women, Franklin said, found themselves in nursing, teaching or as homemakers. And the headhunting services she contacted didn’t keep heavy stacks of files on women candidates. But women’s clubs did, and once the word was out, a flood of candidates found its way to Franklin.

She helped put women into positions for tug boat captain, FBI agent, sky marshall and, yes, the Supreme Court. Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, appointed to the Supreme Court by President Ronald Reagan, was among Franklin’s and the administration’s findings.

Nixon’s task force had made its mark, and Title IX had distinguished itself as a landmark achievement.

“I think it was one of the most consequential legislative activities of the last century. I really do,” Franklin said.

Since then, women have steadily, and sometimes slowly, risen up the ranks of professional sports. The United States Women’s National Team Players Association for pro soccer players only just achieved a collective bargaining agreement that guarantees them equal pay with their male counterparts.

The WNBA has franchises across the nation, and NBA teams like the Boston Celtics and San Antonio Spurs have hired top female assistant coaches, both former professional players.

And, in 2020, Kamala Harris was the first woman elected vice president.

“President Nixon’s actions brought gender equality into the mainstream of American life," Franklin said. “He made equality legitimate.”