When California voters were offered a chance to discard Gray Davis, they had months to consume campaign ads to convince them the governor had to go.

Inexplicable power outages angered the masses, a bloated $38 billion deficit reeked of mismanagement, and a river of candidates swept onto the scene to challenge him.

Davis struggled to connect with citizens in 2003 over these complex issues, and his once glittering approval ratings were beaten downward.

Today, Gov. Gavin Newsom has his own problems as he grapples with sustained unemployment of many service workers, a rental crisis, and lengthy shutdowns of businesses.

Davis’ troubles were different, and distrust was more severe. Compounded by a broader Republican base in 2003, Davis couldn’t survive. At the time, a poll from the Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC) reported that just 24% of likely voters approved of Davis’ performance.

Before then, a successful excision of a California governor had never happened. In fact, only one governor had ever been ousted in the history of the United States.

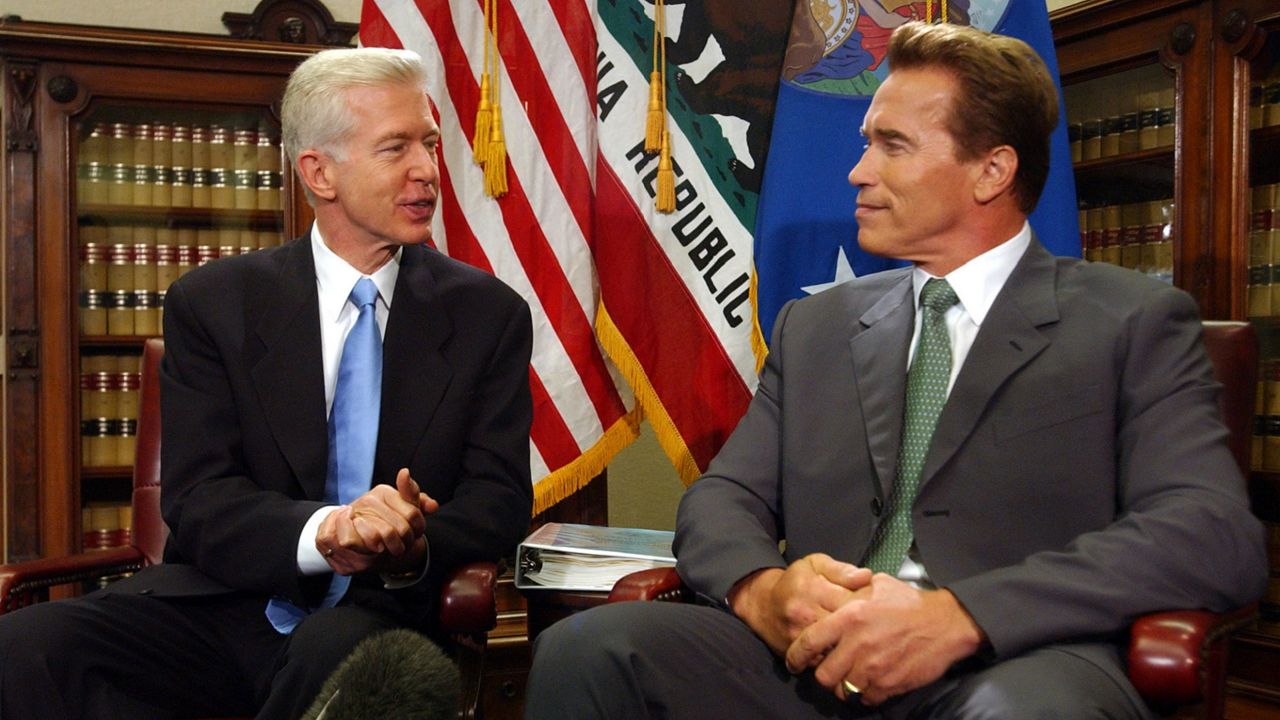

The death blow was the entrance of the once and future Hollywood superstar formerly known the world over as Mr. Universe. Arnold Schwarzenegger blended fiscal conservatism with more liberal social leanings. He wielded a distinctive accent even the least distinguished impressionists could emulate, and he possessed indisputable fame.

“He was married to a Kennedy!” Davis told Spectrum News 1. “Plus he was a famous person with a Democratic connection. Pretty hard to replicate that.”

Along with the megastar Republican, Davis had to contend with power blackouts before Enron publicly emerged as the culprit. Newsom’s task, Davis said, is more straightforward.

“It’s very easy for Newsom to explain that we have this pandemic and everyone is dealing with it,” he said. “We’re sort of in the middle of the pack which is not great, but it’s far better than being the worst. We’re not the worst.”

Coronavirus death tolls and infection numbers are moving targets, but California ranks the highest in both. The state has roughly 3.4 million cases and nearly 45,000 deaths. California is also the most populous state and only recently surpassed the more densely populated New York state. But according to The Washington Post, California is ranked 35th in daily infection rates per capita.

Experts are weighing how serious the bid against Newsom could be, but Davis said he doesn’t see the recall qualifying for an election. Newsom has enjoyed comfortable popularity in a state that has increasingly become a stronghold for Democrats.

A recent PPIC poll showed 52% approval by likely voters. A Berkeley Institute of Government Studies poll showed his approval rating is at 46%. While both numbers are significantly lower than when he first took office, experts say it’s likely high enough to protect him. Only 24% of the state’s registered voters identify as Republicans, and President Joe Biden carried the state by 64%. By comparison, Al Gore’s unsuccessful bid for president in 2003 saw him collect just 53% of the California vote.

Longtime Orange County political consultant and former Republican Jimmy Camp, who has helped manage past recall efforts, said this one needs to be taken seriously.

Newsom’s approval rating may also hinge on the continued rollout of the vaccine, how many people receive it, and how soon the economy can get back to business as usual.

But California’s standards for a recall are relatively modest. Organizers must gather 1.5 million eligible signatures—about 12% of the voters in the November election—and 160 days are allowed to collect signatures. Organizers have until March 17, and though they have collected 1.4 million signatures, it’s unlikely all will be valid. Organizers will likely need to gather at least 20% to 30% more signatures to have enough.

Josh Newman, the Fullerton Democrat representing Senate District 29, has recent experience with this. He was forced into a recall election after just 17 months into his first term.

Like Davis and Newsom, the state senator was accused of hurting his constituent’s wallets. Upon voting for SB1, a 12-cent-per-gallon gas tax designed to fund infrastructure projects, Republicans focused on removing him.

“We didn’t properly explain the bill to voters,” Newman said.

Equally concerning was the stature of his opponent, Ling Ling Chang. With support from the state and local Republican parties, Chang had the resources and name recognition to run a competitive campaign. A former city council member of Diamond Bar, Chang had already served in the state assembly and had lost to Newman in their first encounter by just a few hundred votes.

When the recall arrived, she had enough support to win. But the currents of change had already begun, and the district saw the registration advantage for Democrats double to 4.3%.

While 58% of voters in a special election saw fit to remove Newman, he rebounded in November with a decisive victory over Chang.

“This is really clever by the Republicans because it’s the only shot they have at winning a statewide race right now,” said Tony Smith, UC Irvine professor of political science and the law. “They’ve done a good job, at least in the national press, of creating the idea that Newsom really is in trouble.”

It’s a chance for Republicans with other ambitions to get statewide name recognition, a difficult feat to achieve.

Two candidates to emerge thus far are businessman John Cox and former San Diego mayor Kevin Faulconer. But neither has the kind of name recognition common to successful candidates of statewide races.

Former Gov. Davis doesn’t see anyone competing with Newsom even if an election is forced.

“There’s no charismatic leader,” Davis said. “There’s no Arnold Schwarzenegger.”