SAN GABRIEL, Calif. — After serving six years in the U.S. Navy, an accident on the flight deck 16 years ago caused Jose Miranda to have his leg amputated three times.

Since the accident, Miranda has struggled with PTSD and his mental health.

What You Need To Know

- Veterans Affairs reports that in 2017, there were about 17 veteran suicides on average each day

- Isolation has a negative effect on a veteran's mental health when PTSD is present

- Life Aid Research Institute helps veterans and first responders recover from brain injuries and mental health issues through research, technology and holistic therapies

- A documentary featuring the nonprofit's work, Life Aid: Story of Hope, airs on September 2 on both The Science Channel (2 p.m. PST) and The American Heroes Channel (3 p.m. PST)

“I could smell the JP5 gas or sometimes, I can randomly get the whiff of pure oxygen from the O.R.," Miranda said. "Then I would randomly get dizzy. Like, that’s really the reason why I don’t really go to hospitals."

"I would hear a lot of stories about people being suicidal and I was like, 'That’s not going to be me, that’s not going to be me.' But over the time of shutting down and suppressing my feelings for so long, it became, I became that person,” he said.

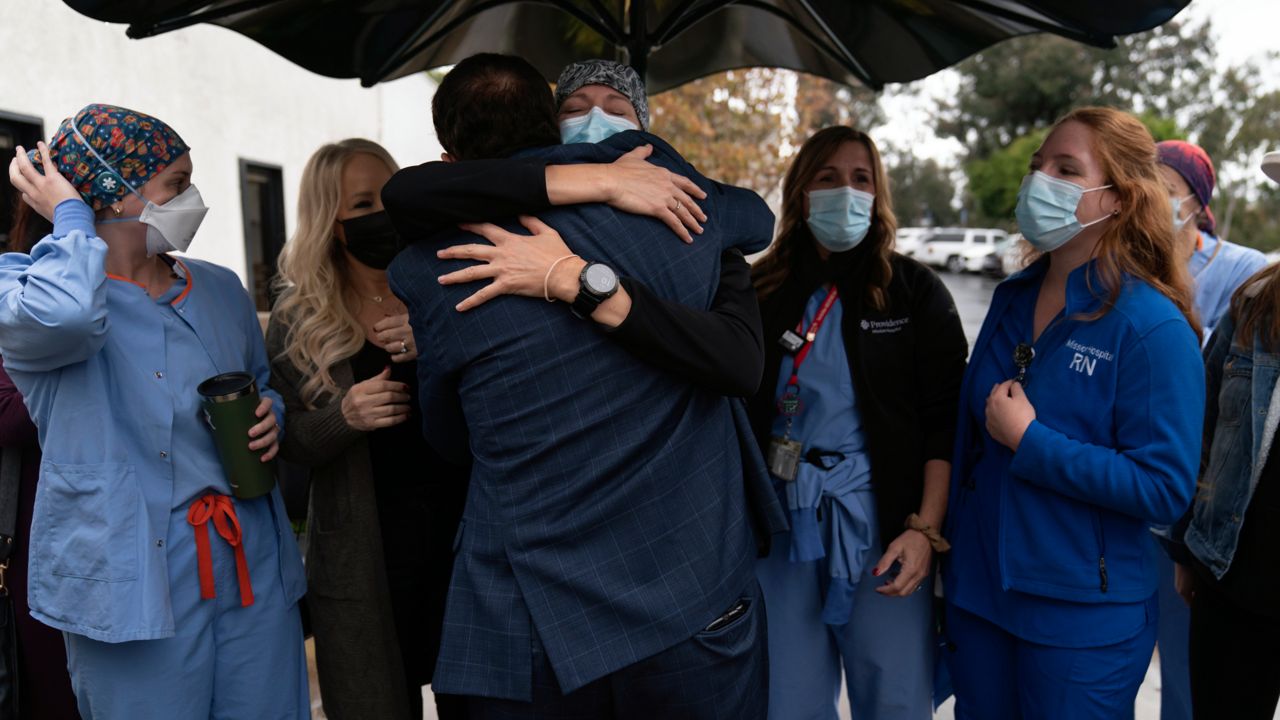

In hopes of finding a way to cope with his PTSD and his amputation, Miranda connected with the Life Aid Research Institute — a nonprofit that provides technology, research-based therapies, community, peer support, and a holistic approach to helping veterans and first responders better cope with brain injuries and their mental health.

The nonprofit’s work focuses on helping veterans cope with PTSD and reducing the risk of suicides in this demographic. A recent Department of Veterans Affairs report found that on average in 2017, about 17 veteran suicides took place each day. One of the driving factors was isolation.

With the pandemic still underway, veterans need to be connected with resources now more than ever, according to the Life Aid Research Institute’s founder, John Wordin.

“Having someone you can trust, that you can go to any time of day or night to unload whatever it is that you need to unload ... the pandemic has crippled that ability," Wordin said. "Now, as an organization we’ve tried to adapt and done online town halls and things, but it doesn’t replace in-person human contact."

Miranda shared that the pandemic hasn’t made his mental health journey any easier. Recently, he discovered that other veterans he served with only recently shared how his accident impacted them.

“He goes, ‘I can’t get your screams out of my mind or the look of your leg when they cut off your boots and your pant leg.’ He goes, ‘I thought you died,'” Miranda said, recounting an exchange with another veteran.

That conversation weighed heavy on Miranda. But through his therapies and the assistance he receives from the Life Aid Research Institute, he shared that he can only take small steps at a time, in hopes of helping others and himself on this journey.

“All of our days are numbered, you know? It’s just a matter of how much better can I love my kids today," he said. "How much better can I love my wife versus how I loved them yesterday or my friends or my family members."

Miranda’s mental health journey with the Life Aid Research Institute will also be highlighted in a one-hour special, Life Aid: A Story of Hope. The nonprofit and Al Roker Entertainment are hoping the special will encourage others to donate to Life Aid Research Institute’s mental health research programs, so they can continue helping others.