ORANGE COUNTY, Calif. — Crowded emergency services for kids and a nationwide surge in yet another respiratory illness have Orange County health officials worried.

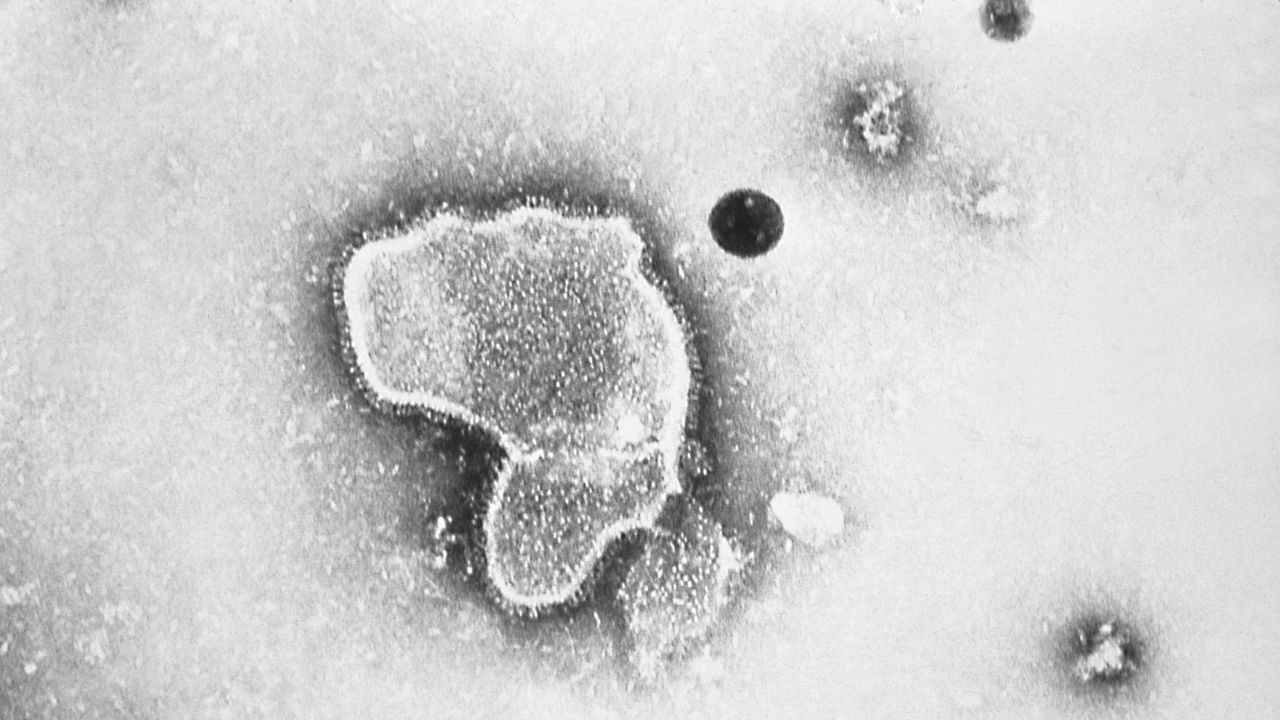

Respiratory syncytial virus, or RSV, isn’t new but has had an outsized presence since officials saw an uptick in cases in August. The county began seeing about 300 patients a day, and that number rose to 400 a day in the last two weeks.

Historically, the most vulnerable groups to the respiratory illness have been infants, people with suppressed immune systems like cancer patients and the elderly.

“Now we’re seeing kids who are five years old getting RSV and landing in the hospital. That’s unusual,” said Andrew Noymer, a University of California, Irvine professor of population health and disease prevention.

RSV has arisen to lock up almost all available emergency care facilities for children in the county, with officials acting to secure waivers that will allow them to place some children in hospitals that don’t generally take pediatric cases.

And officials worry about what will happen once winter arrives and COVID-19 cases spike as they have each of the past two years. With flu and now RSV forcing people to pay attention, some have coined the term “tri-demic.”

Noymer doesn’t expect all three illnesses to have broad enough penetration to warrant such a name. While the flu is currently on the rise right now, he doesn’t expect it to peak at the same time as COVID-19. Flu also has a vaccine, which varies in effectiveness depending on the year.

RSV, however, presents problems it hasn’t presented before.

Noymer said there are two theories.

During the pandemic, kids stayed home from school, preventing them from building a natural immunity to RSV. While most people don’t get severely ill from the virus, Noymer said the common cold can often be attributed to RSV. Without that exposure, kids have an “immunity debt,” which has to be made up.

Noymer favors the second theory, which is that COVID-19 can lower the body’s defense system, dampening the immune system enough to make kids more vulnerable to RSV.

But neither idea has been proven.

“I don’t think we have the data yet to determine which is the answer,” Noymer said. “I can’t fully endorse either one.”

Another concern is that there is no vaccine for infants, and the version that exists for seniors is in trials. COVID-19 vaccines and boosters also have questionable efficacy.

That leaves health officials with rising case numbers in all three respiratory ailments and little idea of how high infection numbers could reach.

The county reports that about 15% of all patients who make it to the hospital are admitted with the most severe symptoms pushed to the head of the line. In the most severe cases, infants can stop breathing. But many experience other symptoms first, like quickened breathing, dehydration or lethargy. Parents observing any of those symptoms should skip urgent care and go straight to the hospital, officials warn.

With a maximum pediatric capacity of about 400 beds in the county, health officials are constantly looking for more emergency beds.

“We try very hard not to transfer kids out of the county. In fact, we’re called day and night to transfer kids into the county,” said Dr. Melanie Patterson, vice president of Patient Care Services and Chief Nursing Officer at CHOC Children’s Hospital.

She and Regina Chinsio-Kwong, Chief Medical Officer and the County Health Officer for the OC Health Care Agency, cautioned people over the holidays. They suggest wearing masks indoors and to stay on top of hand washing.

That advice can translate nationwide, as states across the country have experienced a large bump in RSV cases.

“We’re all experiencing the same surge,” Patterson said. “I think we all know this surge will probably get worse before it gets better.”