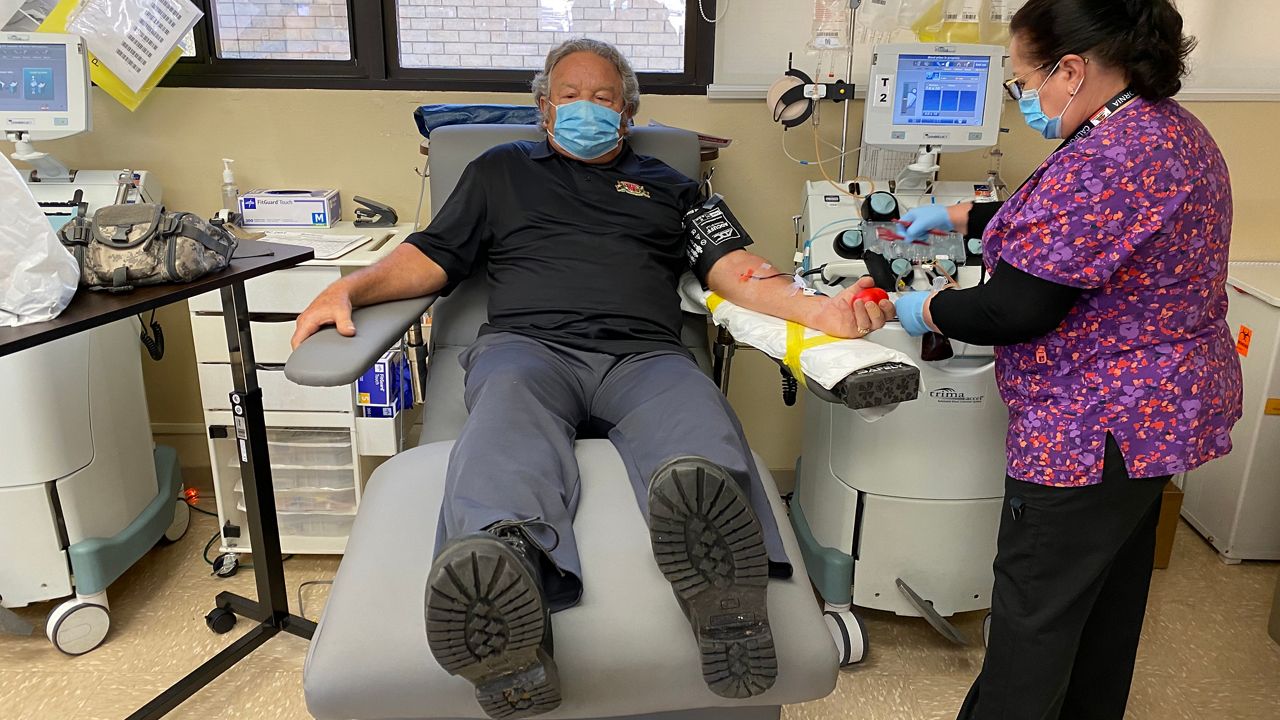

ONTARIO, Calif. — It’s a rare person who has a favorite phlebotomist, but Alan Bleemers is one of them. The 69-year-old retiree from La Verne has been donating blood for 48 years – the last 28 of them at the LifeStream Blood Bank in Ontario, where Halina Youssef happily pricks his forearm roughly every other week.

“The needle sticks don’t bother me, and I figure I can help people out,” said Bleemers, who first started donating blood when he was a junior at Cal Poly Pomona. He has since given 117 gallons.

“My goal is 200,” said Bleemers, who, if he continues donating at the rate that’s legally allowed, will be 85 years old before he meets his goal. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration limits blood donations to 24 per year, or about six gallons annually.

Bleemers is among the 70 percent of unpaid, volunteer blood donors who are regulars, most of whom are over the age of 50 and will eventually become ineligible because of disease or otherwise age out of routine donations, according to the national nonprofit trade association, America’s Blood.

“Demographic shifts challenge the U.S. donor base with the aging of the World War II and baby boomer generations that have supported the blood supply for decades. Millennials and younger donors are failing to donate at similar rates,” said America’s Blood Chief Executive Kate Fry, adding that less than five percent of people who are eligible to donate blood actually do.

COVID-19 has only made cultivating a new generation of donors more difficult. With most colleges and high schools conducting classes with distance learning, the blood donations that happen on their campuses have been canceled.

“In normal times, we rely heavily on school-based blood drives,” said Fry, whose member organizations collect 60 percent of the nation’s blood supply. “Those aren’t happening right now even if school reopened. Workplaces are also still remote, so the blood drives there are also canceled. We’ve really had to transition the way we collect blood in this country.”

In normal times, about 50 percent of blood drives take place at colleges, high schools, and businesses, according to the American Red Cross. Now the Red Cross and other blood donation centers are turning to hotels, hoping to leverage unused ballroom space from canceled events, and, in some areas, sports team arenas to host blood drives in a way that allows for social distancing.

“It’s been a bit of a rollercoaster since the beginning of the pandemic,” said Ross Herron, divisional chief medical officer with the American Red Cross Pacific division. While the early days of the pandemic brought a surge of blood donations in March and April, they have slowed in the months since.

The Red Cross has been freezing blood in anticipation of a COVID surge this fall and winter. Nationally, it currently has 6,000 units of blood, but Herron says the Red Cross needs “in the hundreds of thousands of units.”

Right now, the blood supply is OK, Herron said, “but the thing we’re really lacking and need more donors for is the COVID-19 convalescent plasma.”

Convalescent plasma donations come through two types of donors: those who were hospitalized with COVID and chose to donate their blood afterward, and those who never knew they had COVID but have tested positive for antibodies.

In Southern California, about two percent of the population has COVID antibodies, according to the Red Cross, and those individuals could potentially donate COVID convalescent plasma.

Many donor centers are now offering antibody testing as an incentive to donate blood, including the seven blood banks operated by LifeStream.

“People want to know their antibody status,” said Dr. Rick Axelrod, president and chief executive of LifeStream, which recently added COVID antibody testing to the tests it already runs on blood donations to screen them for infectious disease.

LifeStream collects three different types of blood products from donations: red blood cells (commonly used for traumatic blood loss), plasma (often used to help blood clotting), and platelets (to help during organ transplants and to fight cancer).

“The demand for blood products is much greater than what we’re normally collecting,” Axelrod said, citing a return to elective surgeries that had been stopped for several months during the early days of the pandemic.

Axelrod said his blood banks currently have less than a one-day supply of Group O universal blood to serve the region’s 60 hospitals and is also five to ten percent short of Group A and B platelets. It is now importing those platelets from other parts of the country, he said.

As much blood as Bleemers has given, it just isn’t enough to meet demand. But it’s helping.

“I like donating blood. It's pretty easy for me,” said Bleemers, who aspires to the No. 1 position for most donations at the LifeStream Blood Bank in Ontario. He’s currently fifth. “It’s one of my hobbies besides gardening, lifting weights, riding my bicycle, hiking. I just enjoy it.”