ORANGE COUNTY, Calif. — A long simmering battle over how children should learn to read has taken on a new shape as educators grapple with pandemic learning losses.

Literacy rates among students have been an enduring challenge for teachers nationwide, with a recent dip in reading levels reigniting a debate about teaching methods.

“California is very, very localized. That means when there’s evidence-based approaches, then bringing them to the classroom is really difficult because decisions are made by each teacher,” said Young-Suk Kim, a University of California, Irvine professor and associate dean of the School of Education.

Reading struggles began before the pandemic, according to the National Center for Education Statistics, when nearly two-thirds of students nationwide could not read at grade level.

Kim suggests it’s a problem with the approach teachers use and believes that students should receive evaluation heading into kindergarten, so educators know where they stand.

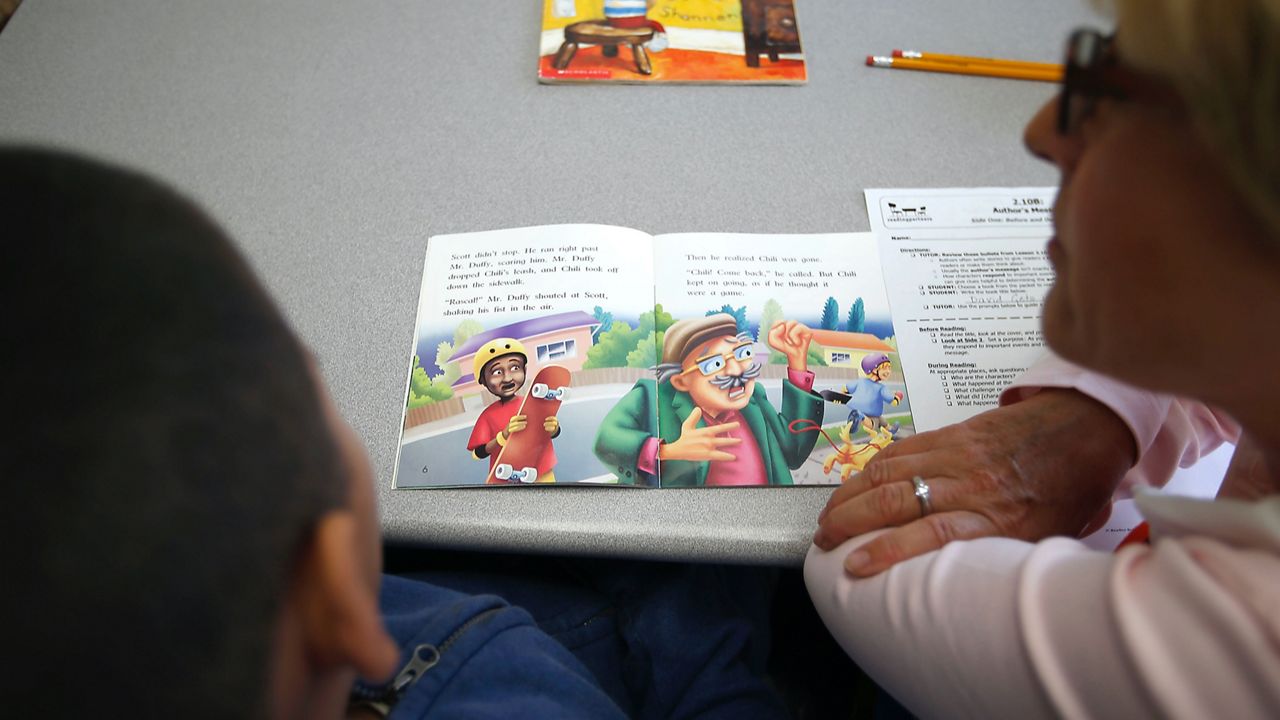

Two main methods of reading include a phonics-based approach and whole language reading. Phonics teaches students to approach words by sounding out letters and letter combinations. Whole-language assumes that exposure to literature and reading will organically develop reading skills in students with no specialized instruction.

In the case of Battle Creek Public Schools in Michigan, administrators saw a below-average reading level in students using a whole language approach. In 2017, they moved to a science-based approach, using the nonprofit American Institutes for Research as a consultant. The remedy has included specialized reading instruction for the teachers, standardizing how the subject is taught. AIR reports that progress in 2019 was promising until the pandemic landed.

Educators pinpoint the third grade as a key time for students to read at grade level. If a student lags, then it can harm their comprehension of other subjects and further delay their learning.

In August 2021, California State Sen. Susan Rubio, a former teacher, introduced Senate Bill 488. which would standardize reading instruction. It includes teacher education in a science-based approach that uses phonics and evaluates students for reading comprehension.

Kim has been included in the legislature appointed Commission on Teacher Credentialing, which was tasked in July with updating a guide of teaching standards to go along with SB 488 as debate continues.

She also advocates for teacher evaluations, something teachers’ unions have pushed back on.

“It’s like anything else,” she said. “You need to be licensed to drive a car as well.”

The pandemic offered a new look into many types of teaching as parents saw their children learning at the kitchen table.

“People were seeing the learning losses in the early wave of the pandemic in particular, and I think more people were witness to their kids’ instruction in ways they aren’t in normal times,” said Morgan Scott Polikoff, associate professor of education at the University of Southern California.

With parents seeing how their kids learned, Kim hopes now is the time for permanent change.

“Who’s suffering is really the students,” Kim said. “And I feel heartache for students who are struggling unnecessarily because they don’t have the right opportunities.”