When Gene Luen Yang walked to school as a kid, he said he transformed. The parts of his brain that had grown around the conventions and expectations of a Chinese household shifted and swiveled into something else. He readied himself to switch from Mandarin Chinese to English, to swap out one set of cultural rules for another.

What remained was still him, but a version prepared for a new audience.

What came later was Yang’s breakout 2006 graphic novel, "American Born Chinese," an exploration of transformation, and the themes of identity and belonging.

The novel, a National Book Award finalist, also collected many racist stereotypes that target Asian Americans, and explored how that ugliness can be internalized and even turn into self-loathing.

“By dealing with it on the page I was able to reach some kind of peace with it in real life and I hope the same is true for my readers,” Yang said.

The book has made the rounds in high school classrooms and eventually helped earn Yang a MacArthur Fellowship.

Racism toward Asian Americans has recently turned into high-profile violent acts, including the killing of eight people in shootings at several Atlanta spas.

Yang, 47, who lives in San Jose, talked about the shootings on his podcast, about conversations with family and friends. At one point they wondered if reports of hatred toward Asian Americans were real, only for the frequency and profile of hate acts to grow.

The source, ostensibly, has been fear and anger stemming from the coronavirus pandemic and conspiracy theories that point to China as a willful creator of the disease. Those fears, critics say, were encouraged by former President Donald Trump who repeatedly called the illness the “China virus” or the “kung flu.”

Now Congress is considering passing legislation to curb anti-Asian American hate.

Racism toward Asian Americans, of course, isn’t new.

“In a lot of ways we’ve moved forward,” Yang said. “But at the same time, there are these voices that would not have been accepted in the public discourse that are being accepted today.”

He said rhetoric from politicians allowed ugly and racist speech to return to public discourse without fear of embarrassment.

While political discourse has intensified, private business and entertainment have lately taken strong positions against racism.

"Saturday Night Live" fired comedian Shane Gillis for remarks show runners deemed racist toward Asian-Americans almost immediately after hiring him.

Politics has seen a recent increase in participation from Asian Americans, including the election last November of Michelle Steel and Young Kim. Both are Korean American women representing districts in Orange County.

Still, reports of hate crimes against Asian Americans continue to surface.

Some of the tension that can lead to racism is contextualized in "American Born Chinese."

Yang contrived the idea for the novel when he was a high school computer science teacher. After years of thinking through three storylines, he realized they were separate parts of the same idea.

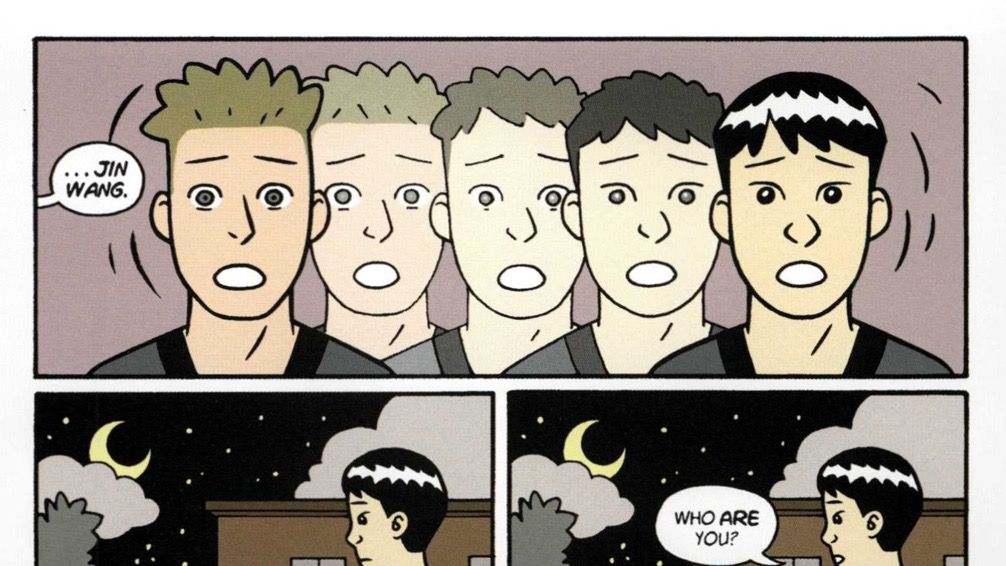

The novel is divided into three alternating stories. There’s a monkey deity who’s banned from a party with the other gods because he’s a monkey; a boy named Jin Wang who’s struggling with high school growing pains; and a character called “Cousin Chin-Kee,” an amalgamation of a multitude of racist stereotypes.

The story uses these stereotypes to illustrate the pain they can cause, especially among the lead character, Jin.

At one point in the book, Jin Wang wishes to become white and blond only to later discover that is no solution.

But within the discomfort of not belonging, Yang said, can endure a hesitation to fight back.

“I think there’s this notion that, as long as we don’t make waves, we can stay in the clubhouse,” he said.

The tension can come down to something as simple as a family name. Yang said his parents considered naming him a more traditional Chinese name, one harder for the American tongue to pronounce. They instead went with Gene, one familiar syllable.

And the story is still closed on "American Born Chinese." Yang doesn’t plan to write a sequel or any other kind of spin off.

But he said the themes of identity and belonging can still be found in his stories, and the page is still a place to empty whatever travels his mind.