SACRAMENTO, Calif. (AP) — Police unions and other law enforcement organizations went into overdrive to thwart a measure that would have added California to the majority of states that can end the careers of officers with troubled histories. It failed as lawmakers scrambled to wrap up their work, and while the nation’s most populous state still has no way to permanently remove problematic officers, a number of other police reforms passed.

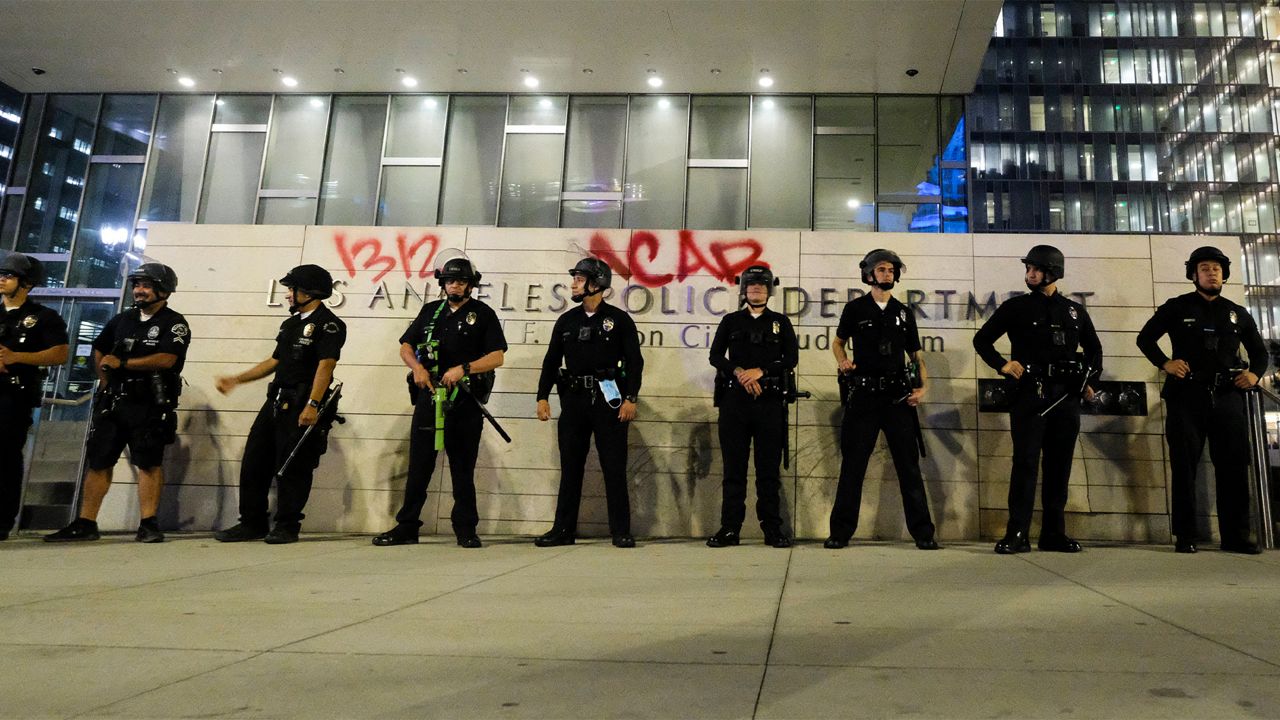

With lobbyists and lawmakers mostly isolated by the coronavirus pandemic, it became a battle of phone calls, colorful graphics and Instagram posts from law enforcement organizations to counter celebrity tweets pushing lawmakers to rein in police brutality after the death of George Floyd last May in Minneapolis and the shooting of Jacob Blake last week in Kenosha, Wisconsin.

“We ended up, for lack of a better term, playing a game of whack-a-mole,” Tom Saggau, a spokesman for police unions in Los Angeles and San Francisco, said of law enforcement efforts to counter support for what he called a deeply flawed proposal.

Even intervention from Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom wasn’t enough to rescue the measure that died without a vote before the legislative session ended early Tuesday. It failed hours after Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputies fatally shot Dijon Kizzee after the Black man dropped a a bundle that included a gun.

The legislation would have created a way to permanently strip badges from officers who commit serious misconduct. Law enforcement groups successfully argued that the proposed system would be biased and lack basic due process protections.

Proposals to reveal more police misconduct records, require officers to intervene if they witness excessive use of force, and limit their use of rubber bullets and tear gas against peaceful protesters also died without final votes.

Lawmakers, however, sent Newsom measures to ban choke holds and other neck restraints, require the state attorney general to investigate fatal police shootings of unarmed civilians, and increase oversight of county sheriffs, among other changes.

“To ignore the thousands of voices calling for meaningful police reform is insulting,” Democratic Sen. Steven Bradford, who is Black, said after his legislation on removing officers failed. “Today, Californians were once again let down by those who were meant to represent them.”

Five states have no way of decertifying police officers who commit misconduct — California, Hawaii, New Jersey, Massachusetts and Rhode Island.

Removing California from that list was a top priority of the California Legislative Black Caucus and had support from hundreds of entertainers, including Rihanna, Mariah Carey and Robert De Niro. Kim Kardashian West caused a stir with a late tweet backing the measure Monday.

Law enforcement organizations and unions insist they also want a way to permanently remove troubled officers so they can’t simply move from one department to another.

The California Police Chiefs Association and a separate coalition of eight Black police chiefs in June called for stripping officers’ training certifications following due process proceedings if they break the law or have a history of egregious misconduct.

The Los Angeles Police Protective League and San Francisco Police Officers Association, which together represent 12,000 officers, on Tuesday reiterated their willingness to negotiate “a fair, reasonable and workable decertification process.”

Their main complaint with Bradford’s bill was the makeup of a proposed nine-member disciplinary panel to consider if officers’ conduct is enough to end their careers. Six of the nine members would be required to have backgrounds opposing police misconduct, while the remaining three would represent law enforcement.

The opponents said that would make the board inherently biased against officers, while Bradford said the mix was needed to restore community trust in police and the disciplinary process.

Law enforcement organizations offered alternative wording, and Newsom’s office weighed in with proposed amendments that Saggau, the police union spokesman, said “would have made it more palatable, more reasonable.”

Bradford rejected those but accepted 40 other changes by Saggau’s count.

“Rejecting some compromise language from the governor, but accepting 40 amendments that drove a wedge further with law enforcement, we think that’s what derailed the measure,” he said.

Bradford declined an interview request Tuesday, but Saggau and Brian Marvel, president of the rank-and-file Peace Officers Research Association of California, said Bradford hurt his bill’s chances by refusing to talk with law enforcement officials.

“When you’re changing a profession, and you don’t talk to the people it’s actually affecting, I think good leaders stand up and say that’s probably not a fair process,” Marvel said.

The lobbying was so intense that Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon set up a special voicemail on his office phone to field comments.

“l think there were a lot of concerns, even with some of our allies,” said Rendon, who supported the legislation.

He said lawmakers have bucked the police lobby in the past, but the measure also ran into opposition from organized labor.

Bradford said he intends to try again next year, and Senate President Pro Tempore Toni Atkins said more work is to be done on several of the policing measures that failed this year.

“Clearly some colleagues felt like there needed to be more conversation, more discussion,” she said, adding that “I think it is our job to make sure we keep the momentum and the conversation happening.”