IRVINE, Calif. — Monkeypox emerged over the summer as a surprise threat, a foreign illness with no natural viral reservoirs in the United States. But even as case numbers have dropped, the future of the illness on U.S. shores remains a concern.

But University of California, Irvine professor of population health Andrew Noymer said it’s nowhere near the threat of COVID-19, especially as cases are expected to spike in the winter.

Monkeypox has even declined since summer highs, with cases hitting over 1,000 a day worldwide for a short period in August. Local Orange County numbers hit 43 a day in August, but as of Sept. 24 were just five a day.

“It remains to be seen whether we’re in a continued decline or if we’ve plateaued,” he said.

Monkeypox does not have the potential impact of the airborne, respiratory COVID-19. Transmitted through skin-to-skin contact, often through sex, Noymer said it’s unlikely to wrap the world up in a global pandemic. It’s also less potent in healthy adults and eventually will run its course.

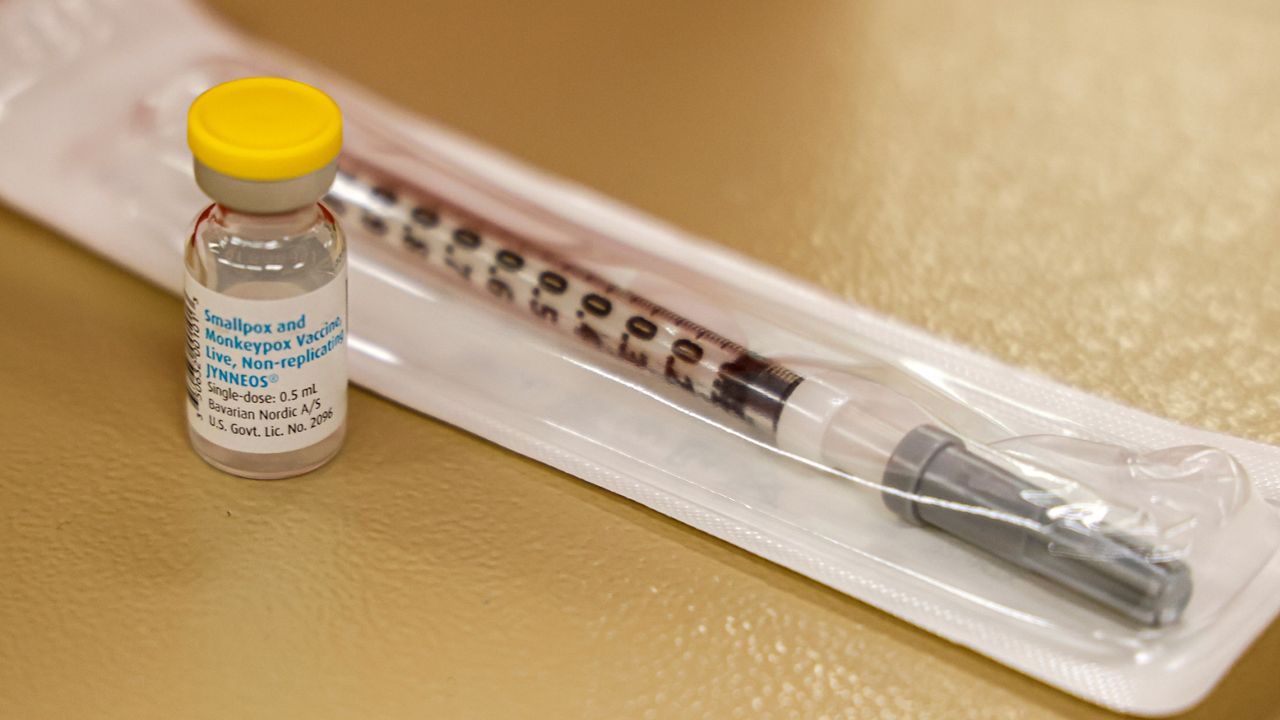

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has also taken action, rolling out vaccines to protect people against contracting the illness.

Noymer worries that the case numbers are high enough that it’ll never completely disappear in the United States.

“In my opinion, it’s uncomfortably high. If you take yourself back to April and you said there was a case of monkeypox anywhere in the United States, you’d have alarm bells ringing,” he said. “It’s an imported disease that doesn’t occur here.”

While it’s impossible to guess whether monkeypox could find its way into local mammal species, it's dangerous to certain populations like the very young, the very old or other people with pre-existing conditions.

“Once it worms its way into the fabric of human life, it can bounce around from case to case to case and there are all kinds of questions about whether it’s being properly diagnosed,” he said.

COVID-19 has also been difficult to diagnose as many people who contract it never show symptoms. Monkeypox is a different story, as it manifests itself through sores or lesions on the skin.

“My biggest concern is that it can become endemic now at a very low level just because there are so many cases out there,” Noymer said. “And God forbid it finds its way into some squirrel population here. Then we’ll never get rid of it.”