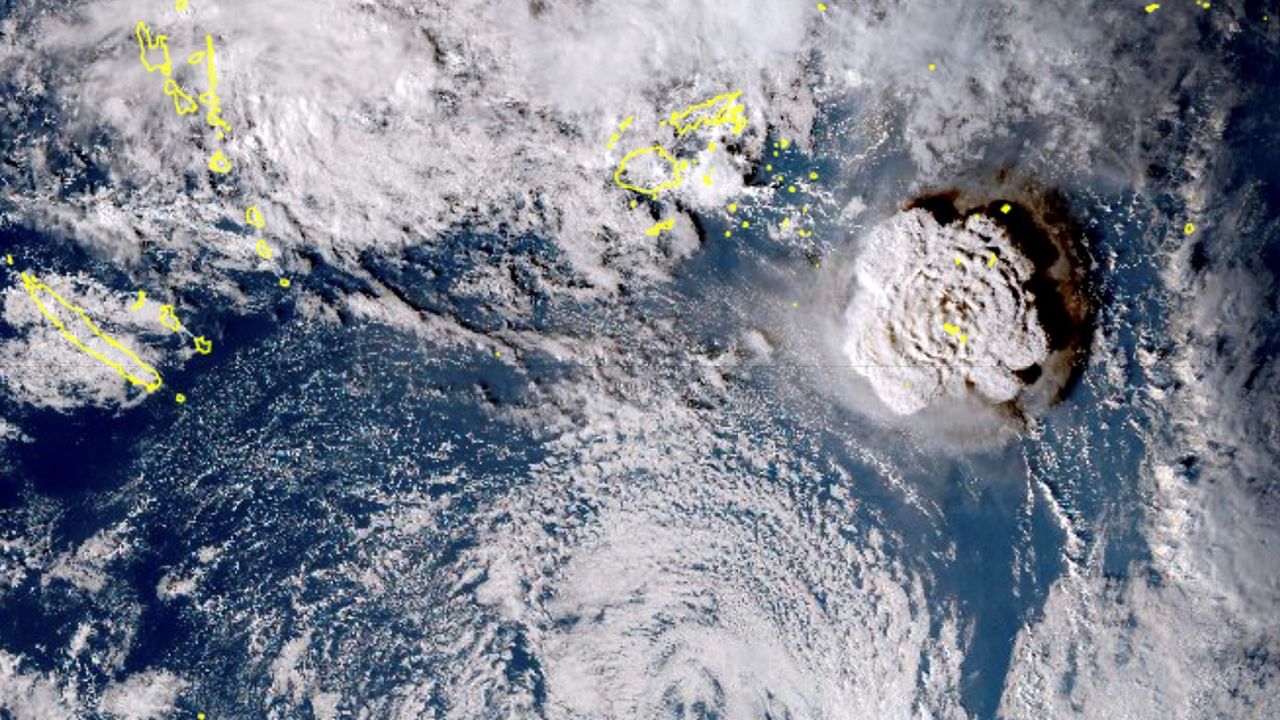

On Jan. 15, 2022 an underwater volcano violently erupted. According to data from a NASA satellite, some 58,000 Olympic-sized swimming pools' worth of water vapor was released through the atmosphere and into the stratosphere.

What You Need To Know

- On Jan. 15, 2022 the Hunga-Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai volcano erupted

- The volcano was located roughly 500 feet below the ocean surface

- The violent eruption sent a massive plume of water vapor into the stratosphere

- The impacts are expected to last a few years and may cause the planet to warm

We live on a very active planet, not only in the atmosphere, but within the Earth. Because of plate tectonics and hot spots within the Earth's crust, we have earthquakes, mountains, valleys, oceans and volcanoes.

Some volcanoes can erupt violently. In the continental United States, the last violent eruption was Mount St. Helens in 1980. The last violent eruption on the planet occurred on Jan. 15, 2022. The Tonga volcano was the strongest eruption since Mt. Pinatubo in 1991.

The volcano was unique as it was under relatively shallow water about 500 feet below the surface. According to NASA's measurements, the force of the Tonga eruption was somewhere between four and 18 megatons. This is hundreds of times more powerful than the atomic bombs dropped in WWII.

The force of the blast caused major damage to the Tonga nation. Since it was in a shallow sea, it sent not only ash, but water vapor (the gas form of water) some 25 miles through the atmosphere and into the stratosphere.

While some volcanic eruptions can cool the planet due to ash blocking sunlight, some can warm the planet because of vast amounts of water vapor injected high into the stratosphere.

This may be the case with the Tonga eruption, due to the incredible amount of water vapor that reached high into the atmosphere.

In a study published in Geophysical Research Letters, scientists estimated that the Tonga eruption sent around 146 teragrams (or 161 million tons) of water vapor into Earth’s stratosphere–equal to 10% of the water already present in that layer. This is four times the amount sent into the stratosphere from Mt. Pinatubo's eruption that impacted Earth's climate.

Luis Millán, an atmospheric scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California, said, "We've never seen anything like it."

Our team of meteorologists dives deep into the science of weather and breaks down timely weather data and information. To view more weather and climate stories, check out our weather blogs section.