MADISON, Wis. — Marilyn Krause found her passion for cooking and baking later in life.

“When your dad is a chef and your mom is a good cook, you really don’t have to cook,” said Krause. “There’s always someone to do it.”

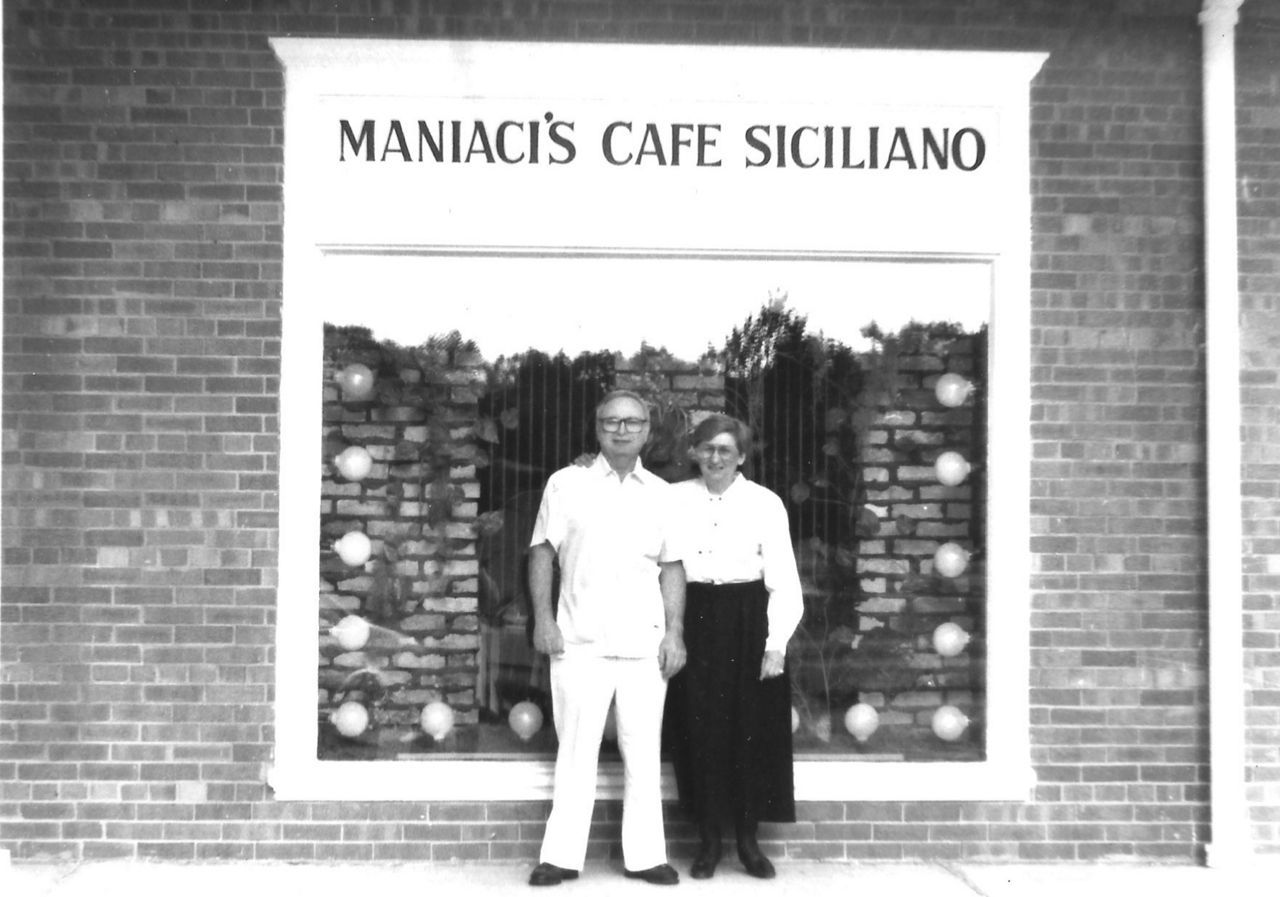

Her parents, Arthur and Rose Maniaci, owned Maniaci’s Cafe Siciliano in Fox Point. Italian cuisine was her father’s speciality. She said he knew his recipes from memory.

“My dad was optimistic,” said Krause. “Very happy-go-lucky. Hard working. When you have eight children, you have to work really hard to support them.”

Over the years, her father’s health started to decline. He was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease.

“He still did a lot of cooking and baking but then as things progressed, he lost the ability to follow a recipe and he knew it,” said Krause. “I think that was very difficult for him.”

A few years after her father passed away from the disease, Krause saw an ad in the local paper for an Alzheimer’s disease clinical trial at UW Health in Madison.

“They were looking for people 65 and older or people 55 and older with someone in their family who had Alzheimer’s and I had qualified both ways,” said Krause.

After a series of tests, she was selected to participate in the AHEAD Study. It’s an international clinical trial aiming to prevent the disease and create a treatment that delays memory loss.

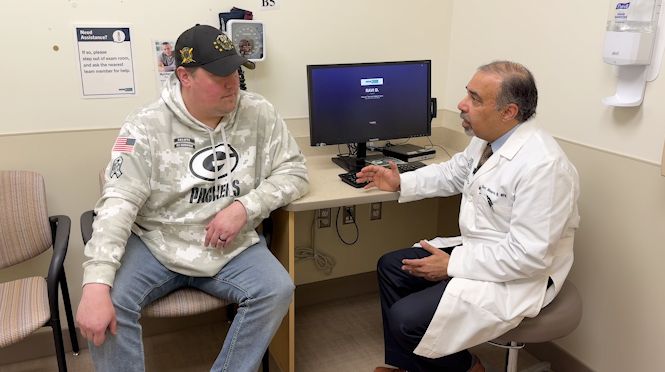

Dr. Cynthia Carlsson is leading the trial at UW Health.

“We’ve known for a long time that amyloid and tau are two proteins that build up in the brain of people that are at risk for Alzheimer’s and over time, as these proteins set up in the brain, it eventually causes damage to the nerve cells in the brain and people, eventually memory capacity,” said Carlsson.

She said participants will receive infusions of either Lecanemab, an FDA-approved drug that removes beta-amyloid from the brain, or a placebo.

Participants with an intermediate level of amyloid on their brain, such as Krause, will receive the infusion every four weeks for four years.

Those with elevated levels will receive the infusion every two weeks for the first two years and then once every four weeks for the remainder of the study.

Carlsson said it’s a blind study with each patient going through four years of infusions.

“So that means if somebody doesn’t start the study until three years from now, they wouldn’t [be done] until seven years from now,” said Carlsson. “So, we wouldn’t find out any results, no sneak peeks at how effective the therapy is until that time.”

While some days are better than others, Krause thinks of her late father and her husband, who passed away from cancer.

“Sometimes the drug is delayed and I’m here a really long time,” said Krause. “Sometimes the IV doesn’t go to well and it’s pretty painful, but I think about people like my husband who went through chemotherapy and other treatments for cancer. What I’m doing is nothing to what those people go through because I’m not sick. I have the good fortune to be healthy and contribute.”

Krause said she is proud to be a part of research that could potentially make a big impact for many facing Alzheimer’s and their caregivers. She’s hopeful that one day families won’t have to deal with the disease.