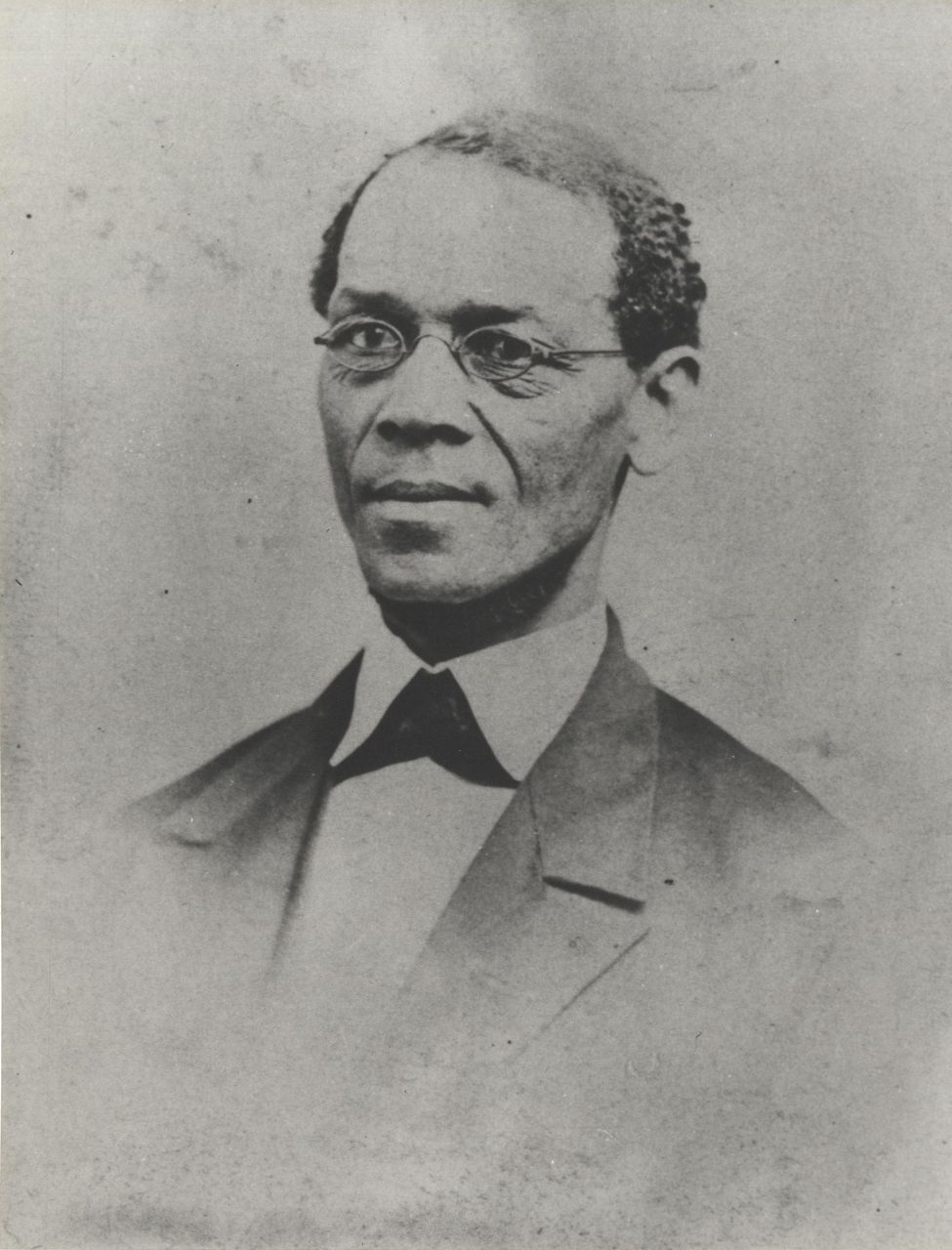

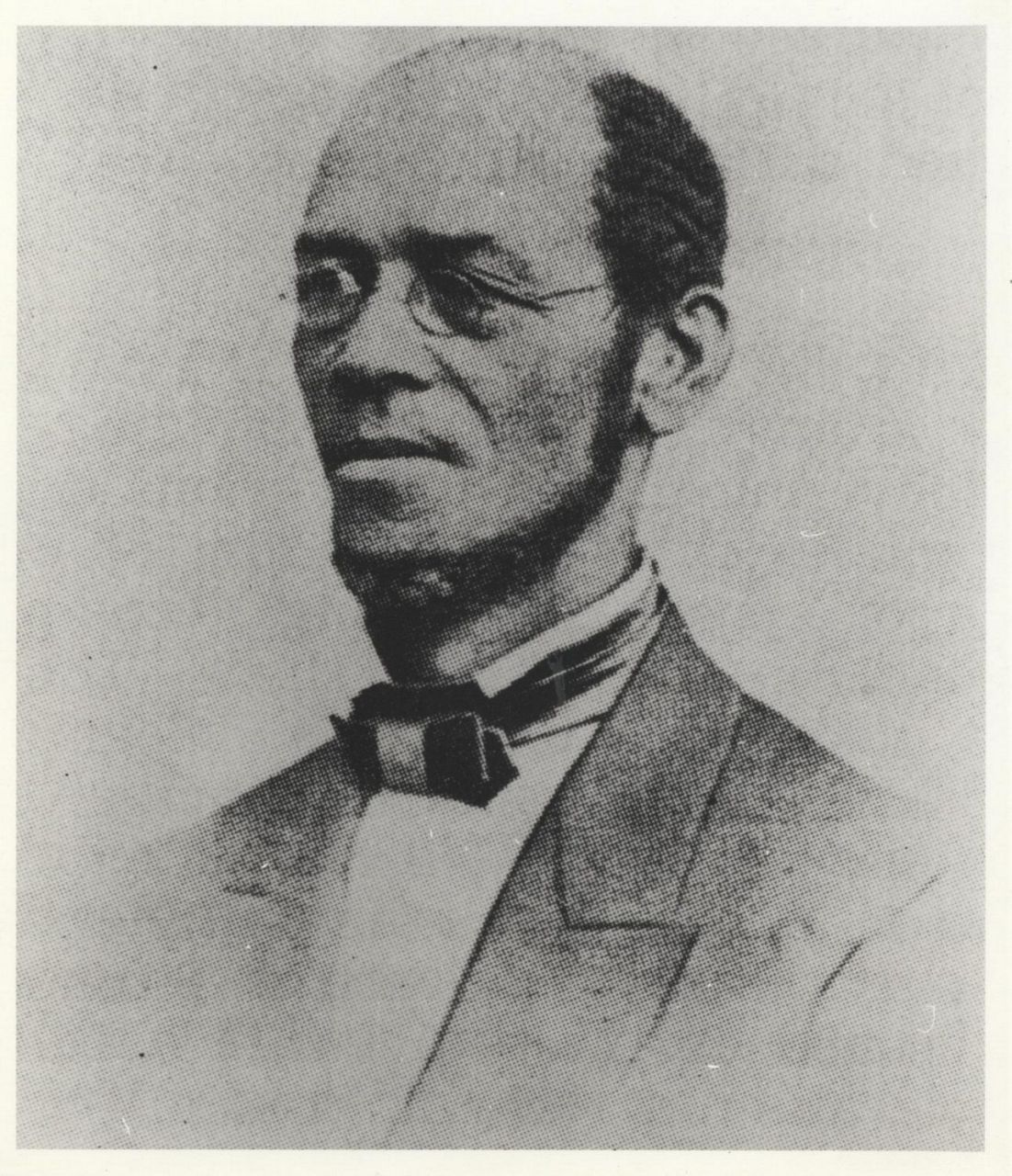

MADISON, Wis. — You may not know the name Ezekiel Gillespie, but you should.

“He’s born around 1818,” said UW-Madison history professor Christy Clark-Pujara. She specializes in the Black experience during that time. “Most Black people are not free in that time period.”

Gillespie was one of them. He was born enslaved in Tennessee.

“The vast majority of African Americans are living in bondage, and are involved in the cultivation of cash crops,” Clark-Pujara said. “Gillespie was most likely living on some kind of tobacco farm, performing that kind of labor. That's what was being done in Greene County, where he was born and where he grew up.”

In young adulthood, he managed to buy his way out of bondage. “We know he bought his freedom from his enslaver, who was also his father.”

But the feeling of freedom didn’t last long. In the 1840s, Gillespie was living as a free man in Indiana.

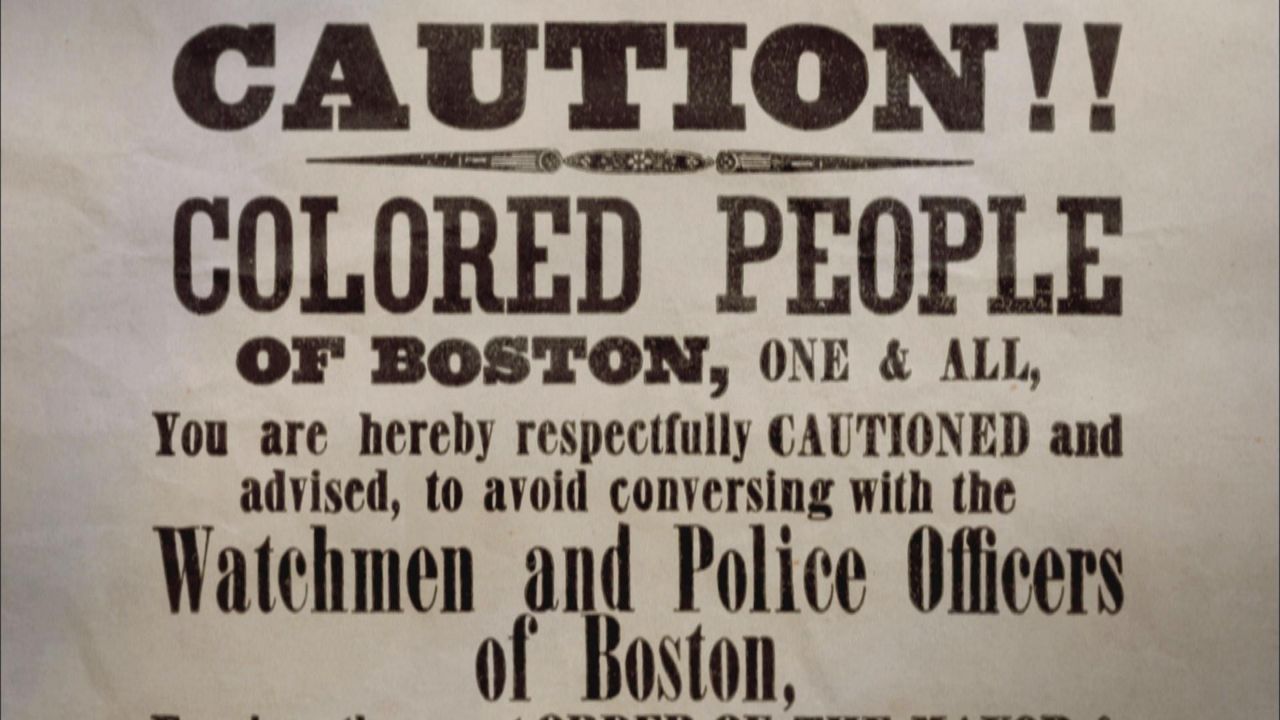

In 1850, the Fugitive Slave Laws passed. It didn’t matter whether you were free or not: any black person could be in danger of being sent to bondage. “You have black people that are moving even further north, as they try to make sure they are safe,” Clark-Pujara said.

Ezekiel Gillespie was part of that movement to travel north to ensure his own personal safety. That’s how he ended up in Milwaukee.

“By 1842, he's in Milwaukee, selling groceries and vegetables and poultry and game on Mason and Main Street,” she said. “He advertised in the Milwaukee Free Democrat. And so that's how people knew where to find him and his goods.”

Wisconsin was not some Northern safe haven from all enslavement. The lead rush meant enslaved people were here in the Badger State doing back-breaking labor every day.

“You have enslaved people in Wisconsin that are bringing up thousands of pounds of lead a day,” Clark-Pujara said. “Our first territorial governor Henry dodge brings five enslaved people with him from Missouri, when he's a lead prospector.”

It wasn’t just Gillespie, he had his family there with him.

“This is somebody who married twice, has 11 children, two of them are stepchildren,” Clark-Pujara said. “He's widowed twice. He's working full time jobs. He's a community activist. He's a loving husband and father.”

He was part of the Black community fighting for equal rights. He was involved in getting people to safety through the Underground Railroad.

“There are meetings being held in Wisconsin by African Americans, as they're being held all over the country, as black people are fighting for their rights and fighting for access to liberty,” she said.

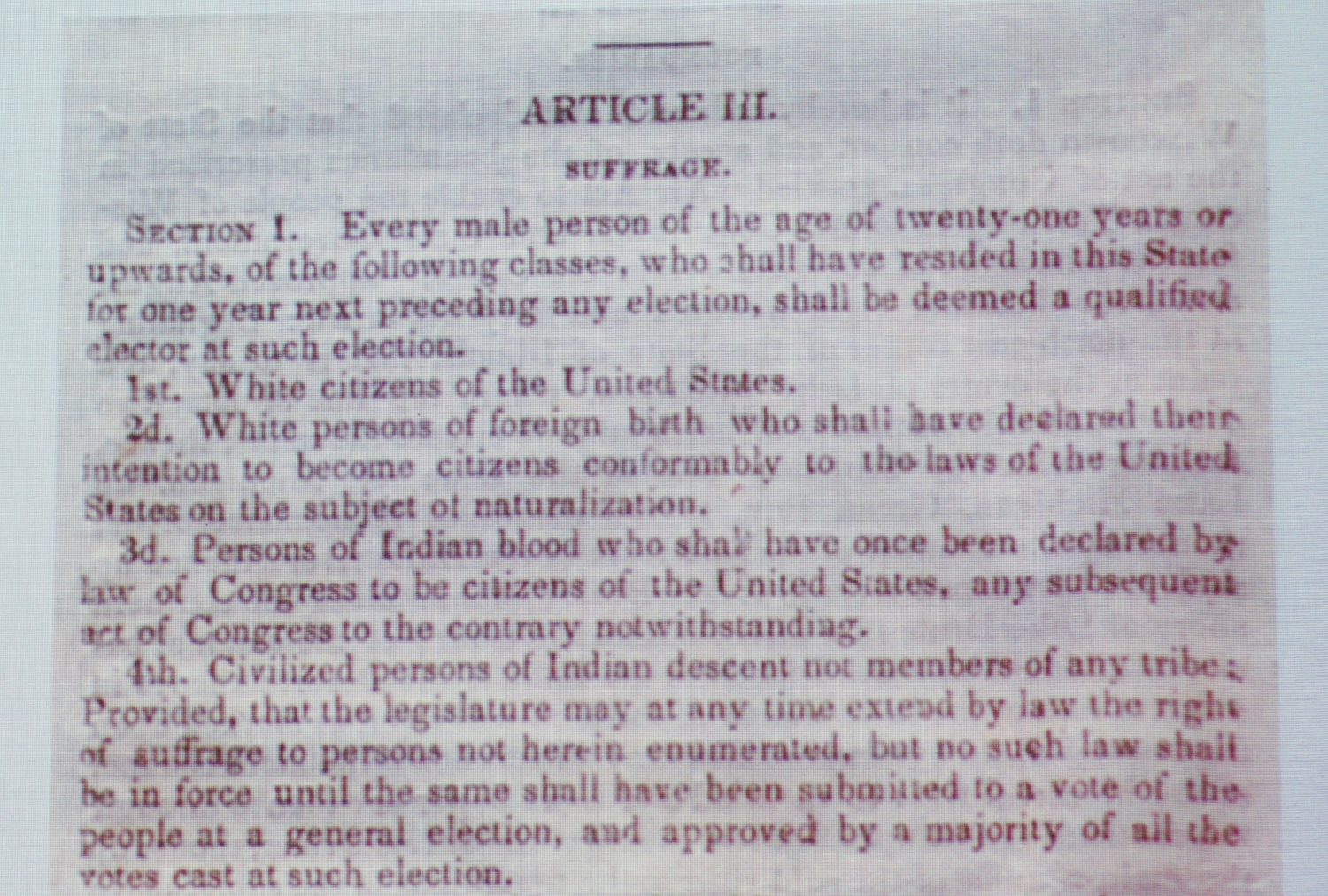

A big part of that liberty was the right to vote. The roots of white supremacy are obvious in Wisconsin’s 1848 constitution, which gives the right to vote only to white men and certain Native Americans.

“It’s a white supremacist document,” Clark-Pujara said. “He understands that black people have been very specifically and pointedly left out of the electorate.”

There were referendums on Black suffrage in Wisconsin. A 1849 referendum failed on a stunning technicality: they counted all the people who didn’t answer the question at all, as “no” votes, against Black suffrage. Meanwhile, the majority of people who answered the question answered “yes”, approving the right to vote for Black men.

Later referendums didn’t pass because the majority of white men with voting rights rejected them.

Gillespie, along with the Black activism community in Milwaukee, was chosen as the face of a new push for Black suffrage in 1865.

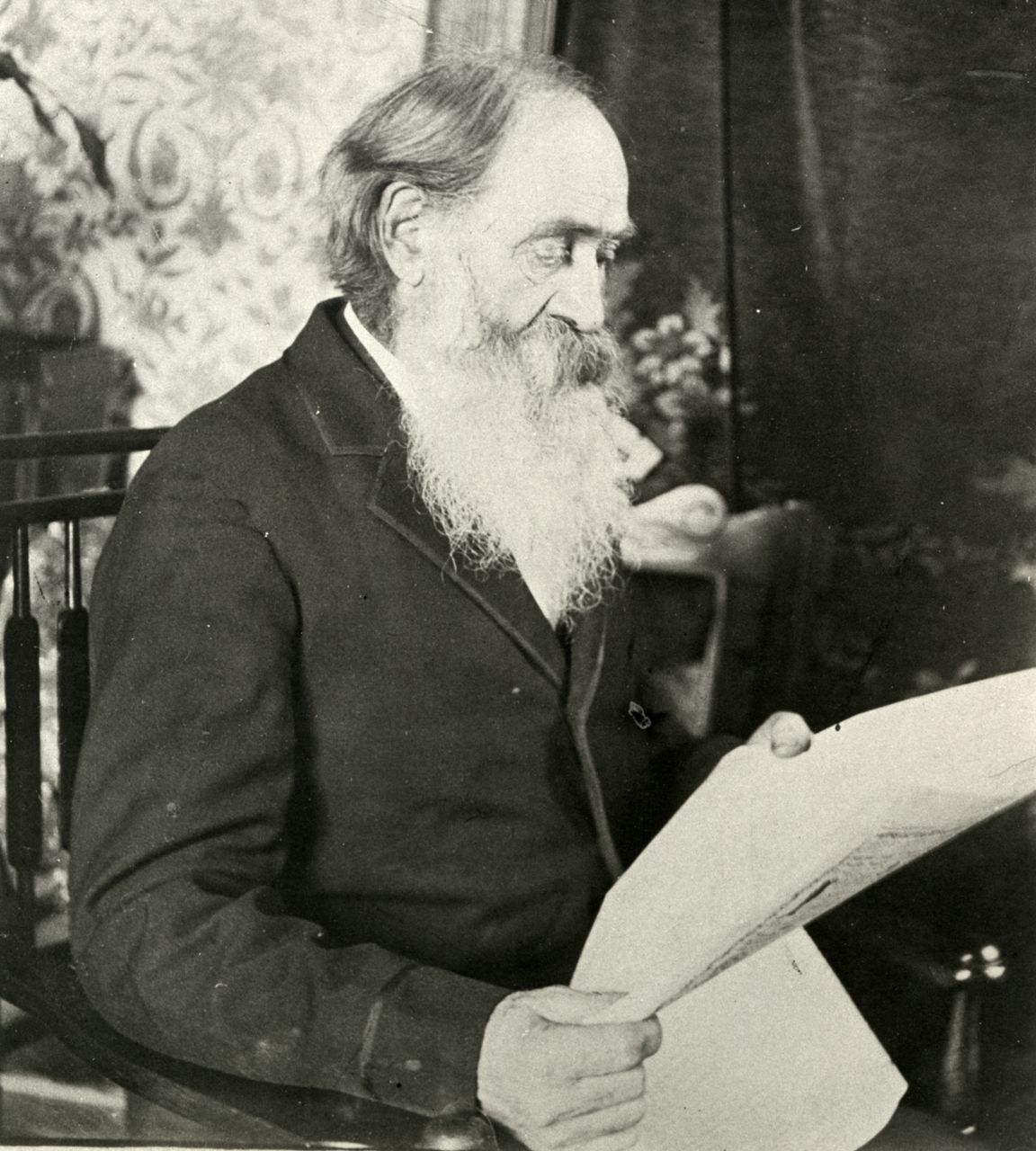

“Ezekiel Gillespie goes to the polling place to vote, knowing he's going to be turned away. This wasn't his first time doing so,” Clark-Pujara said. “But this time, he's accompanied by Sherman booth, to witness him being turned away. So he can file suit.”

Sherman Booth is a Wisconsin abolitionist lawyer and newspaper editor who fought for people who escaped enslavement.

Booth and Gillespie filed a lawsuit against the Board of Elections. The case went all the way to the Wisconsin Supreme Court.

In 1866, the court ruled that Black men have the right to vote in Wisconsin.

But this decision was not rooted in the principles of equality; it was basically a loophole. They ruled that the 1849 referendum should’ve passed, which meant the voters approved Black men’s right to vote.

“They rule on a technicality,” Clark-Pujara said. “That is how black men get access to the vote.”

Wisconsin was the first state in the Midwest to grant unrestricted voting rights to Black men. Ezekiel Gillespie was Wisconsin’s first Black person to cast a ballot.

Clark-Pujara makes it clear that he was just one person, and there are other Black people who helped in this movement whose names weren’t on that lawsuit. She said he’s just one part of the resistance Black people have been fighting for hundreds of years, to keep moving the country, and Wisconsin forward.

“He had great loss in his life, he loses two wives, he loses a child, but he works full time and commits himself to his community,” Clark-Pujara said. “He's determined to leave a better world for his children. And he did that.”

“He's a reminder that is the best of us.”

Special thanks to the Wisconsin Historical Society for their help and materials telling this story.