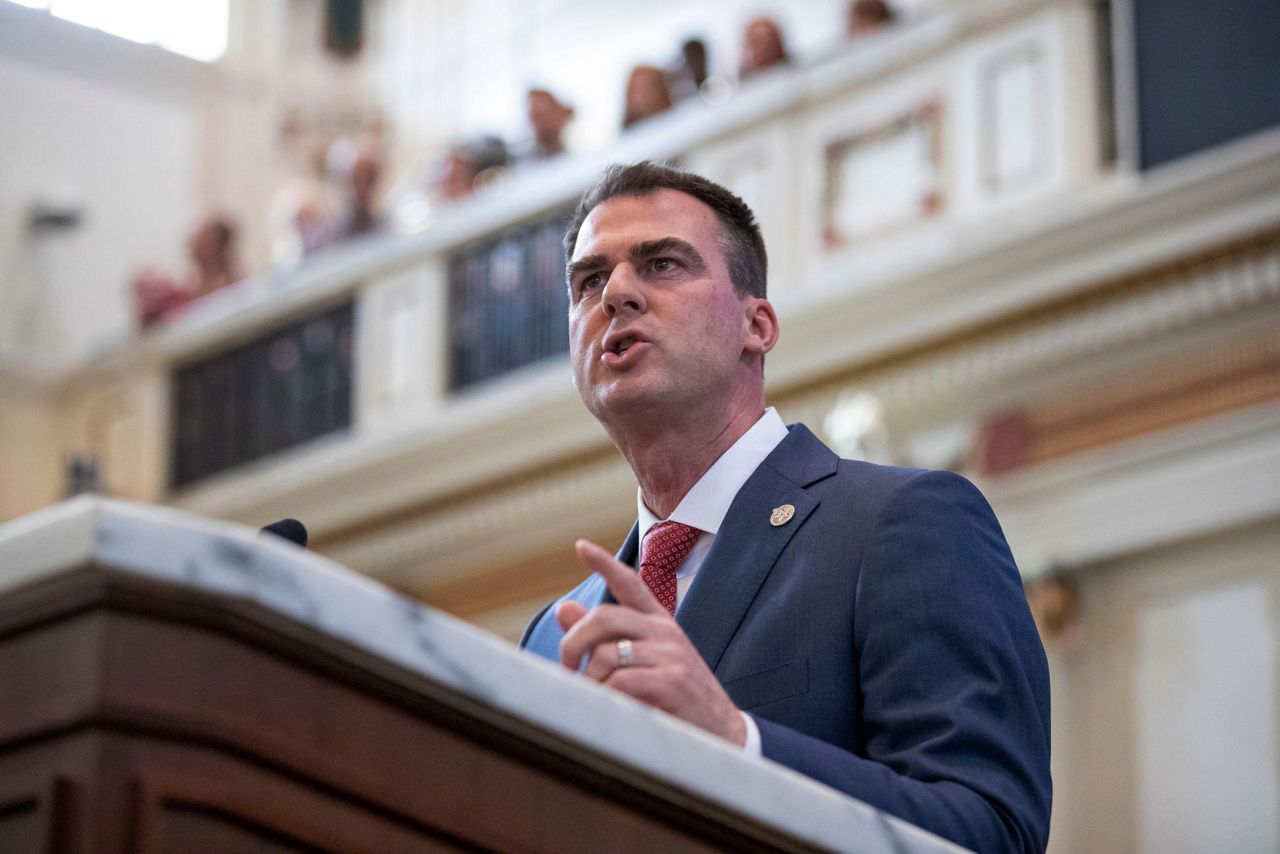

When Republican Kevin Stitt was elected Oklahoma governor in 2018, many Cherokee Nation members felt proud that one of their own had accomplished such a feat, even if their politics didn't necessarily align with his.

But in less than a year in office, Stitt began facing fierce blowback, particularly from fellow tribal citizens, for engaging in a battle with the Cherokee Nation and other Oklahoma-based Native American tribes over the amount of casino gambling revenue they were giving to the state.

Many of the 39 federally recognized tribes in the state quickly united and launched a slick, multi-million-dollar ad campaign touting the benefits the tribes bring to the state. One fellow Cherokee Nation member launched an online petition that labeled Stitt a “traitor” and sought to have his tribal citizenship revoked. And several Cherokee genealogists have separately questioned Stitt’s ancestry, providing documents that indicate that the governor's ancestor fraudulently got the family on the tribe's citizenship rolls more than 100 years ago.

The fight is the first real test of power for the mortgage company CEO-turned-governor, and it is raising questions about tribal citizenship and identity, and the role that plays in politics.

“It’s one thing to be able to claim a heritage, and it’s a whole other thing to respect what that heritage means,” said state Rep. Collin Walke, a Democrat from Oklahoma City who is a Cherokee Nation citizen and the co-chair of the state'sNative American legislative caucus.

“Gov. Stitt’s affiliation with the tribe, I think he used that as a talking point, not so much as a substantive appreciation of what his actual heritage is."

Several tribal leaders say the way the governor outlined his casino revenue plans — with an opinion piece in a Tulsa newspaper — was a disrespectful way to approach negotiations with sovereign nations. And tribal officials are undoubtedly concerned about any effort to undermine their control over an industry that has exploded across Oklahoma, generating millions of dollars in revenue for the tribes to spend on health care, education and infrastructure. More than 130 casinos now dot the state, including several glittering Las Vegas-style complexes, and they generated more than $2 billion in revenue last year, including nearly $150 million that went to the state.

Claiming Native American heritage can be a politically risky for a politician, especially if there’s an impression that it’s being done for political gain. Democratic presidential hopeful Elizabeth Warren learned that lesson when she used DNA test results to try and rebut the ridicule of President Donald Trump, who derides her by referring to her as “Pocahontas,” which is a slur. Warren ended up angering many Native Americans and later apologized.

Unlike Warren, Stitt is a recognized citizen of the Cherokee Nation, which uses lineal descent to determine citizenship. That means a person can apply for citizenship if they have an ancestor who is listed on an original tribal roll.

According to archived tribal documents from the early 1900s that were reviewed by The Associated Press, the Cherokee Nation sought to remove one of Stitt’s ancestors, Francis M. Dawson, from the tribal rolls, alleging that he bribed a commission clerk to get him and his family on them. The tribe’s decision to remove Dawson and his family ultimately was overruled by the federal government, which had enacted a law that said anyone on the 1880 Cherokee census would be enrolled, said David Cornsilk, one of several Cherokee genealogists who has studied Stitt’s ancestry through records available in the National Archives.

Stitt declined a request to discuss his lineage but said through a spokeswoman that he never knew about an attempt to remove his ancestors from tribal rolls until a reporter recently asked him about it. He said he felt the line of inquiry was “highly offensive” and a distraction from the more important issue of the gambling compacts.

The Cherokee Nation’s new principal chief, Chuck Hoskin Jr., also declined a request to discuss Stitt’s ancestry, and the tribe said in a statement that its was focused on the mediation of its gambling compact.

“Governor Kevin Stitt is a citizen of the Cherokee Nation and our tribe does not dis-enroll our tribal citizens, nor is the Nation associated with any related petitions,” the tribe said.

Cornsilk, the Cherokee genealogist who works for the tribe but doesn't speak on its behalf, described Stitt as a disconnected tribal citizen who doesn’t vote in tribal elections or actively participate with the tribe or in its traditions.

“Now, I don’t judge him for that because a lot of our citizens fall into that category,” Cornsilk said. “What I do judge him for is the fact that he’s attacking our tribe and tribal sovereignty and our gaming compacts.”

The dispute flared up suddenly when Stitt announced last summer that he wanted to renegotiate the 15-year-old gambling compacts that give tribes the exclusive right to operate casinos in exchange for paying the state between 4% to 10% of revenue. Those fees generated nearly $150 million for the state last year, most of it for public schools. Stitt, who wants a larger share for the state, argues that tribal casinos in many other states pay significantly more. The two sides also disagree about whether the compacts automatically renewed on Jan. 1, and a federal judge has ordered both sides into mediation.

Republican legislators are divided on the issue. Many of them come from districts whose schools, roads and health care systems have benefited from tribal contributions. While some GOP lawmakers say it's a good idea to re-examine the industry and the state's share of revenue since the gambling market has matured, others are scratching their heads about why Stitt would pick a fight with the state’s tribal nations.

“They’re not mad at him, they just don’t understand why,” said state Rep. Ken Luttrell, a citizen of the Cherokee Nation and a Republican whose northern Oklahoma district is home to five tribal nations and at least eight casinos. “I don’t think any of us do.”

Sarah Adams-Cornell, a Native American rights advocate and a citizen of the Durant-based Choctaw Nation, said the dispute has wrecked the good will that Stitt had with Native Americans, who make up more than 9% of the state's population.

“I was initially incredibly encouraged and excited about having a governor who would understand what it's like to live as an indigenous person," Adams-Cornell said. “I feel very disappointed, and more than that, just let down."

___

Follow Sean Murphy on Twitter: https://twitter.com/apseanmurphy

Copyright 2020 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.