CLEVELAND — Research four years in the making at Case Western Reserve University has provided hope for the future of renewable energy battery storage.

“We're actually getting into going from the fundamental research into transitioning, into how they actually perform in devices,” said Robert Savinell, a university professor of chemical engineering at Case Western Reserve University.

Savinell said as how much renewable energy is provided on the power grid continues to rise, new ways to store the energy are needed, because the sun doesn't always shine and the wind doesn’t always blow.

He leads a team of researchers working to develop the next generation of batteries aimed at providing large-scale, long-lasting energy storage solutions for renewable energy. But they’re not doing it alone.

CWRU has partnered with eight other colleges and universities to help them with this research. They include The Ohio State University, University of Tennessee, Texas A&M, Hunter College, University of Notre Dame, Columbia University, New York University and Pacific Northwest National Laboratory.

“That's our passion is the electrochemistry,” Savinell said. “But now we're taking that passion and we're using it for solving significant societal problems.”

Right now, there are batteries that can store wind and solar power, but he said they’re made from materials that are expensive and also not readily available. Case Western Reserve University is working to make a battery that is cheaper and easier to obtain.

“We're looking at different approaches for the future that can drive down the costs, but also make them more sustainable and more environmentally friendly and more safer,” Savinell said. “We bring to our table, our creativity, our understanding of the basic sciences and trying to put these things together to try to find solutions that will benefit the world.”

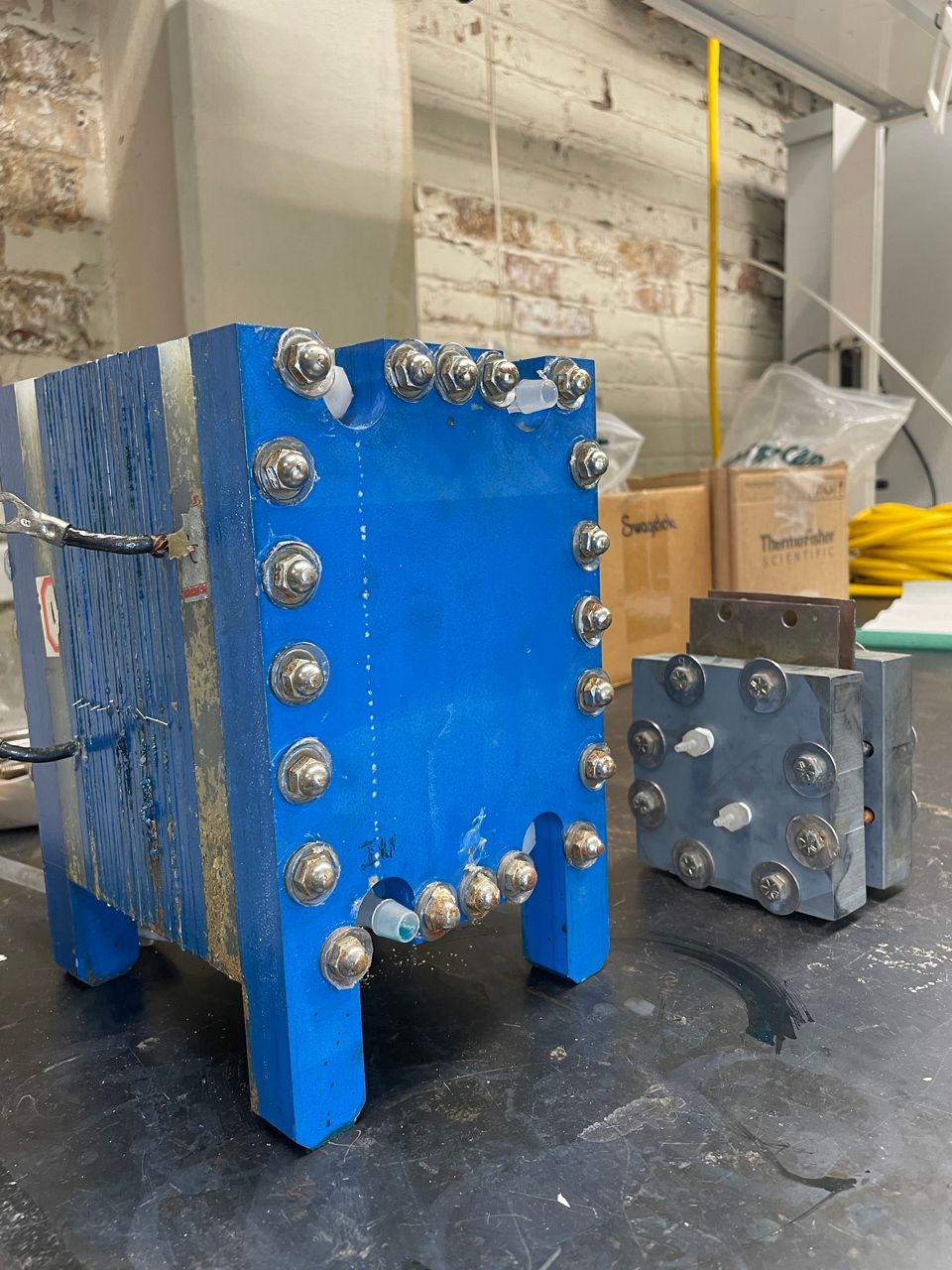

Their work aims to allow so-called flow batteries to store electricity anywhere from two hours to two weeks.

“These got to be very large systems. We’re talking about 10s of megawatt hours’ worth of energy you’re trying to store,” Savinell said. “The idea though, in our research is to understand the structure of the systems, to understand how they would actually perform in terms of transporting ions and carrying out electrochemical reactions that you actually store the energy in."

The research is funded by the Department of Energy, which awarded CWRU a four-year $12 million grant to continue the work of its Breakthrough Electrolytes for Energy Storage Center (BEES). The BEES Center was initially funded in 2018 with a $10.75 million grant from the Department of Energy.

Savinell said the next four years will be focused on discovering new materials and testing them in prototypes. The end goal is to scale the battery system up, commercialize it and put it to practical use. However, research by nature is slow, so Savinell said it will likely be 10 years at least before the work has any practical application.

“At the end of this the next four years, we hope to have new materials that have been identified, that we've discovered, that we've fabricated, we tailored to, that can meet these type of energy storage goals we need in terms of low costs, in terms of having high performance and then being tested in actual flow batteries and leading into commercialization,” Savinell said. “So at that time is when we'd be looking at partners to move it into a commercial product for energy storage.”

They’re aiming to lay the groundwork for the next generation of technology, with goals of transforming energy storage so more renewable energy can get on the grid and help power our world without harming it.

“We're well on our way,” Savinell said.

For more information about the research, click here.