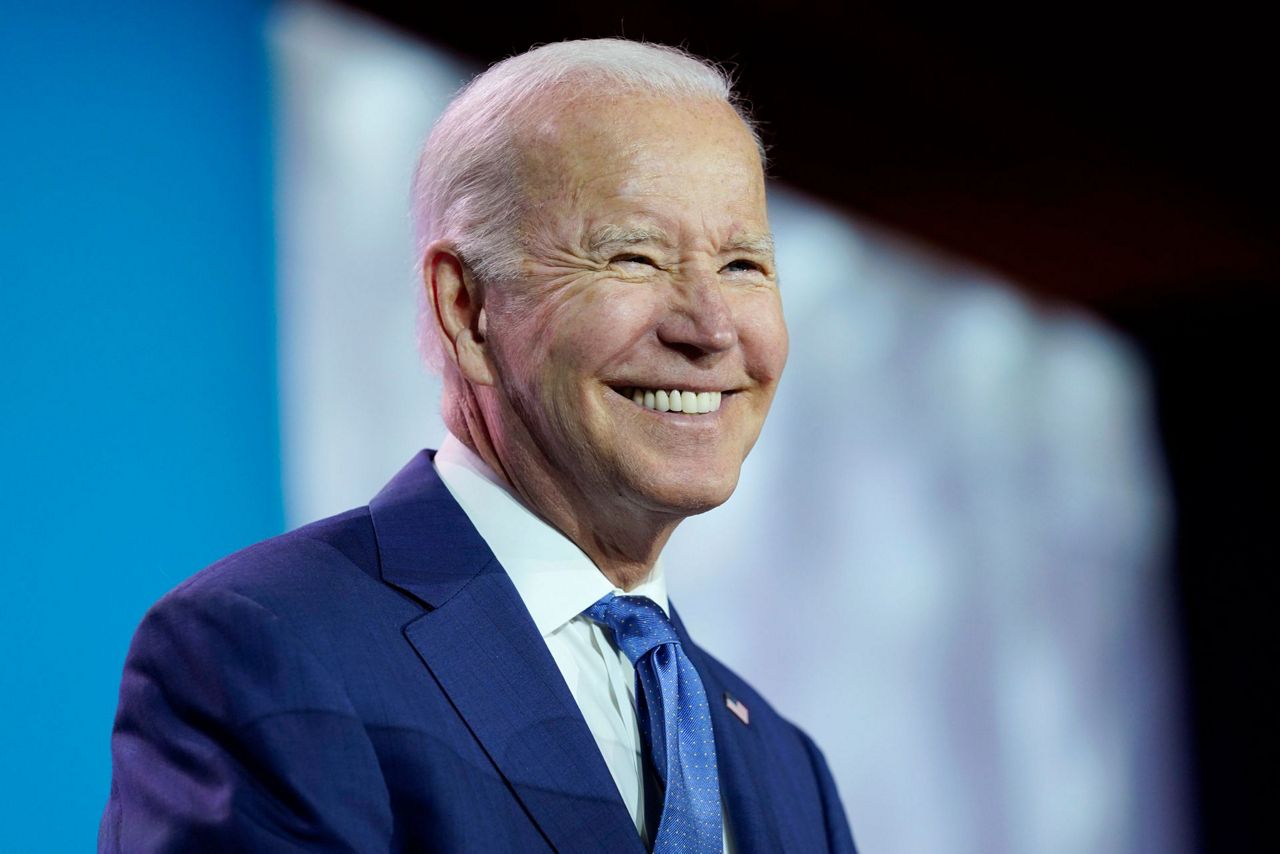

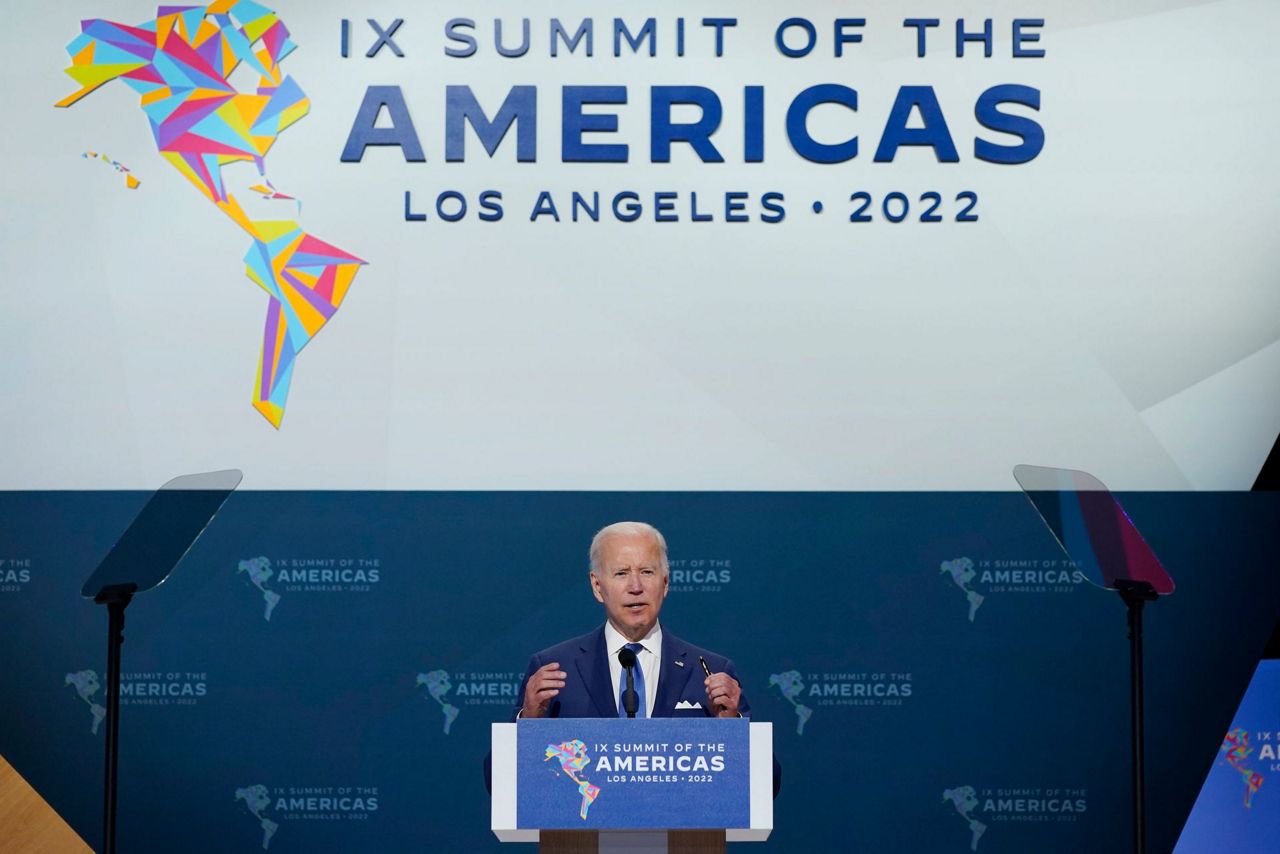

LOS ANGELES (AP) — President Joe Biden tried to present a unifying vision for the Western Hemisphere on Thursday but the Summit of the Americas quickly spilled into open discord, a telling illustration of the difficulties of bringing together North and South America around shared goals on migration, the economy and climate.

“There is no reason why the Western Hemisphere can’t be the most forward looking, most democratic, most prosperous, most peaceful, secure region in the world,” Biden said at the start of the summit. “We have unlimited potential.”

Quick on the heels of Biden's remarks, Belize's prime minister, John Briceño, publicly objected to countries being excluded from the summit by the United States and to the continued U.S. embargo on Cuba.

“This summit belongs to all of the Americas — it is therefore inexcusable that there are countries of the Americas that are not here, and the power of the summit is diminished by their absence,” Briceño said. “At this most critical juncture, when the future of our hemisphere is at stake, we stand divided. And that is why the Summit of the Americas should have been inclusive. Geography, not politics, defines the Americas."

Additional criticism came from Argentina's president, Alberto Fernández.

“We definitely would have wished for a different Summit of the Americas," Fernández said in Spanish. “The silence of those who are absent is calling to us.”

The backlash over exclusions, which included a boycott by the Mexican president, came despite a consensus reached at the 2001 summit in Quebec City that future conferences would not include undemocratic governments. Biden, speaking later, tried to smooth over the differences by focusing on the issues at hand rather than on the guest list.

“I think we’re off to a strong start. We heard a lot of important ideas raised,” Biden said. “And notwithstanding some of the disagreements relating to participation, on the substantive matters what I heard was almost uniformity.”

The disparities in wealth, governance and national interests have made it challenging for Biden to duplicate the partnerships he has assembled in Asia and Europe, setting low expectations at a summit hosted by the U.S. for the first time since 1994.

“It’s always been difficult to find consensus in Latin America,” said Ryan Berg, a senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington-based think tank. “This is a hugely diverse region, and it’s obviously difficult for it to speak with one voice.”

With diplomatic efforts strained and legislative proposals stranded in a polarized Congress, Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris focused on trying to get companies behind their efforts.

“The private sector is able to move quickly to mobilize vast amounts of investment capital that’s going to be needed to unlock the enormous potential for growth in this hemisphere,” Biden said at an event with business leaders.

On a busy day of diplomacy, Biden met with Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and agreed to visit Canada in the coming months, two government officials familiar with the plans told The Associated Press. They were not authorized to discuss the matter publicly and spoke on condition of anonymity.

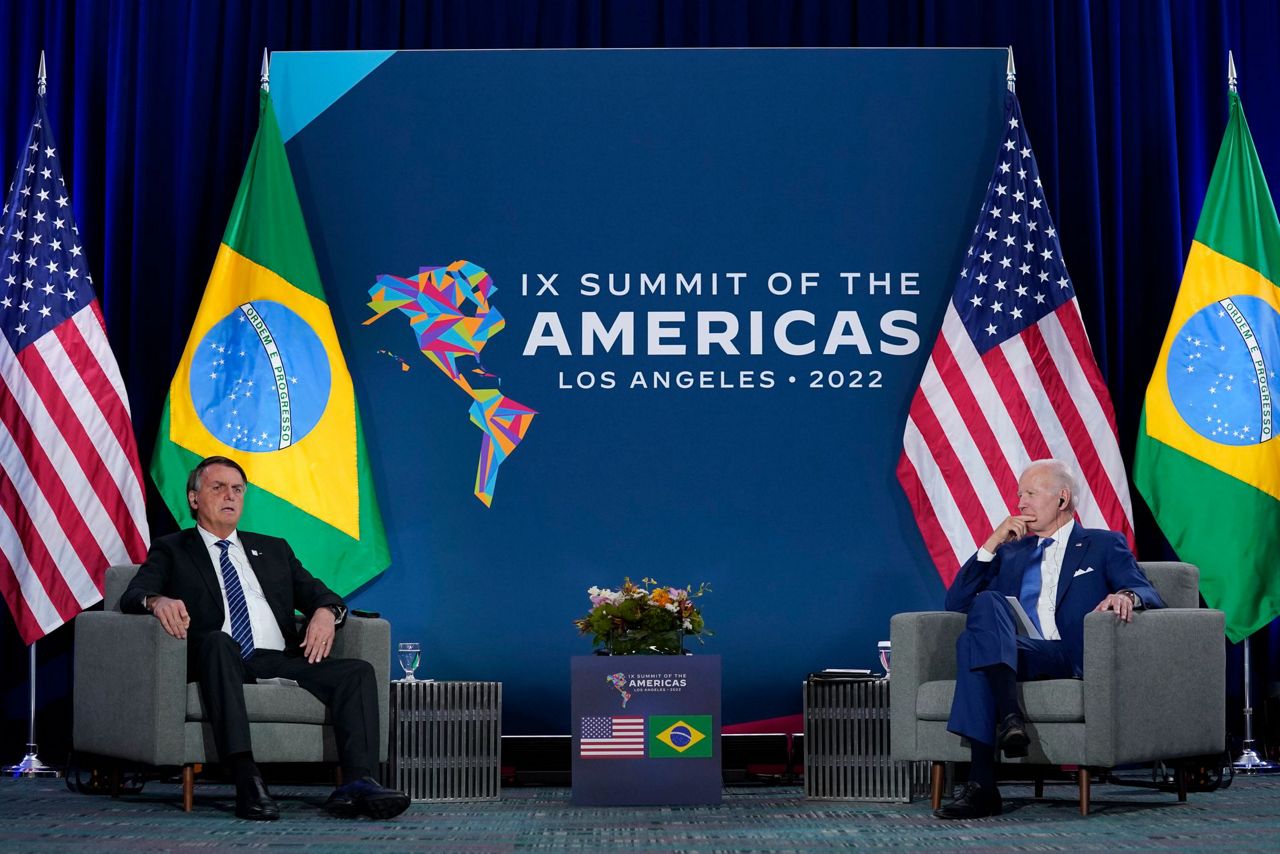

Biden held talks with Brazil's president, Jair Bolsonaro, an ally of former President Donald Trump. Bolsonaro is running for a second term and has been casting doubt on the credibility of his country’s elections, to the alarm of officials in Washington.

Bolsonaro had asked that Biden not confront him over his election attacks or Amazon deforestation, according to three of his Cabinet ministers who requested anonymity to discuss the issue.

Biden refrained from doing so during the brief, public portion of their meeting, although he made a reference to Brazil’s “vibrant, inclusive democracy and strong electoral institutions.”

The U.S. president also said Brazil has made some “real sacrifices” in protecting the Amazon, and “I think the rest of the world should be able to help you preserve as much as you can.”

Bolsonaro appeared defensive on both issues. On the Amazon, he said, “at times we feel threatened in our sovereignty in that region of the country” and that “we stand as an example in the eyes of the world when it comes to the environmental agenda.”

He said he wants Brazil’s election in October to be “clean, reliable and auditable so there is no doubt after the vote," repeating a frequent falsehood that the current system cannot be audited.

“I am sure that it will be held in this democratic spirit,” Bolsonaro said in Portuguese. “I rose through democracy and I am sure that when I leave the administration it will also be in a democratic way.”

Recent polls show Bolsonaro largely trailing former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, who could return to the job he held between 2003-2010.

The nature of democracy itself became a sticking point when planning the guest list for the summit. Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador wanted the leaders of Venezuela, Cuba and Nicaragua to be invited, but the U.S. resisted because it considers them authoritarians.

Ultimately an agreement could not be reached, and López Obrador decided not to attend. Neither did the presidents of Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador.

Biden addressed the issue only briefly on Thursday. Asked by reporters if he was concerned by the boycotts, he offered an emphatic “no.”

The controversy is a reminder that relations with Latin America have proved tricky for the administration even as it solidifies ties in Europe, where Russia's invasion of Ukraine has prompted closer cooperation, and in Asia, where China's rising influence has rattled some countries in the region.

One challenge is the unmistakable power imbalance in the hemisphere.

World Bank data shows that the U.S. economy is more than 14 times the size of Brazil, the next-largest economy at the summit. The sanctions the U.S. and its allies levied against Russia are much harder in Brazil, which imports fertilizer from Russia. Trade data indicates the region has deepening ties with China, which has also made investments.

This leaves the U.S. in a position of showing Latin America why a tighter relationship with Washington would be more beneficial at a time when economies are still struggling to emerge from the pandemic and inflation has worsened conditions.

One example of that came when Harris met with Caribbean leaders to talk about clean energy and climate change.

Biden dropped by the meeting to make his own pitch for closer ties.

“This is a partnership," he said. "We’re not here to dictate. We’re here to learn.”

___

Boak reported from Washington. Associated Press writers Debora Alvares in Brasilia, Brazil, Mauricio Savarese in Sao Paulo, Brazil, Rob Gillies in Toronto, Canada, and Elliot Spagat in Los Angeles contributed to this report.

Copyright 2022 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.