CANTON, Ohio — Aaron Culbertson is a free man with a cleared name, four years after he was arrested for aggravated robbery at 16 years old.

Culbertson, 21, returned home to Canton after spending his late teens in prison for aggravated robbery, a crime he did not commit. His release resulted from an unlikely alliance between the Ohio Innocence Project and a Stark County prosecutor.

“I feel like special, like, it makes me feel, like, like one in a million for real because this doesn’t… this doesn’t really happen, especially not in Ohio,” Culbertson said.

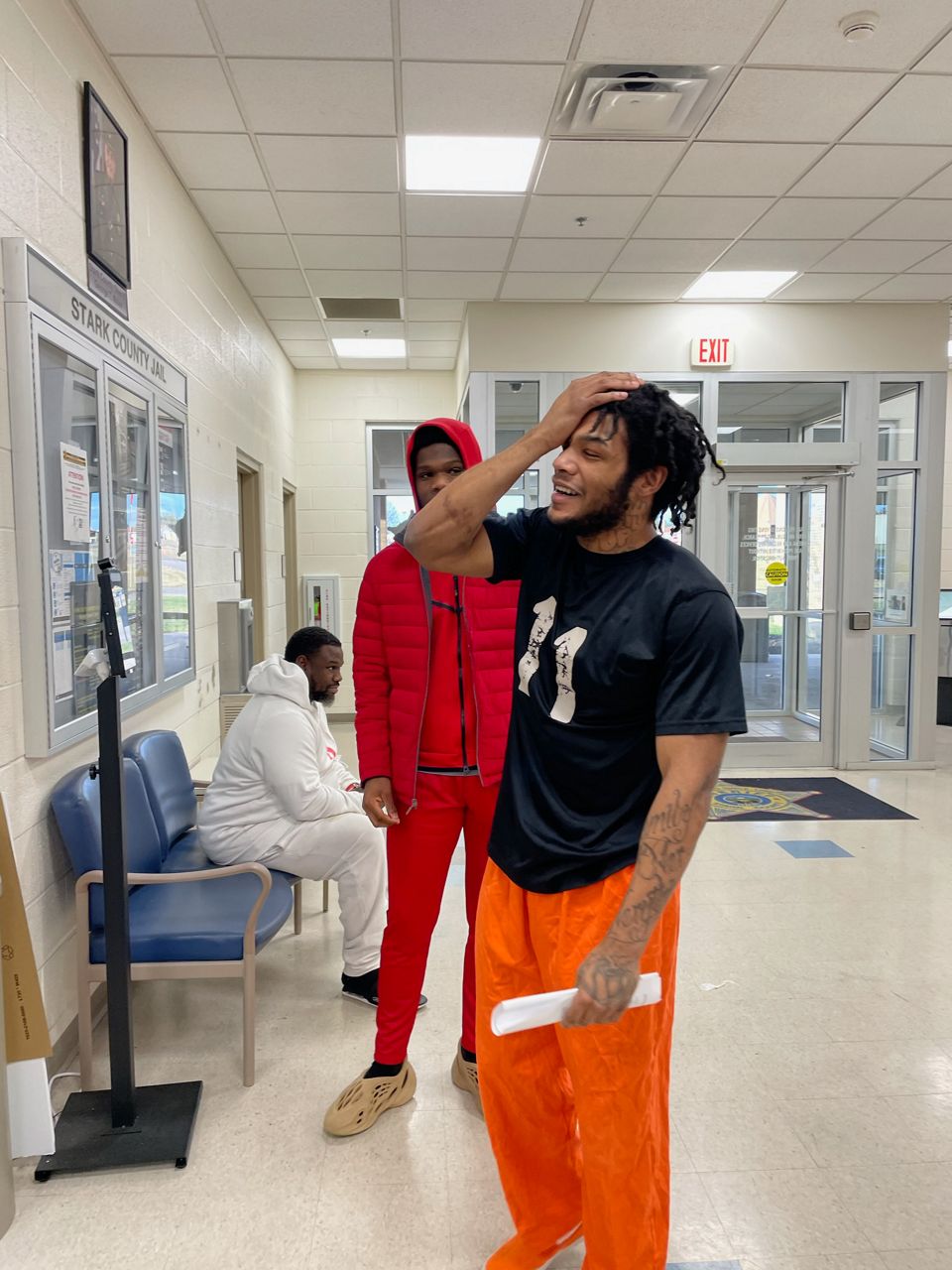

Culbertson was released in December, halfway into his eight-year sentence. He had an emotional reunion with his sister, Val Ryan.

“’Cause I didn’t even get to visit him for the four years,” she said. “So, I haven’t seen him other than video visits.”

Culbertson always maintained his innocence, even during initial police interviews.

“I’m 110% sure that I don’t have a gun,” he said at the time. “I didn’t rob nobody, and this isn’t me.”

Culbertson might not have gotten his freedom now without Stark County Prosecutor Kyle Stone, who immediately realized it was a case of misidentification that caused an innocent teenager to be tried as an adult and convicted as a violent offender.

“For me, I can clearly see this is the wrong individual,” Stone said. “How did this happen?”

Culbertson’s conviction and now exoneration hinged on a surveillance video. The video was taken outside Harmon’s Pub in Canton around the time of the crime in Feb. 2018. Two suspects rushed a woman near her car, held up a gun and demanded her purse.

“And they had dark hoodies on and black leather gloves, and their hoodies were almost covering their face,” the victim told police in an interview. “I did get to see somewhat of the one face. The guy with the gun.”

Prior to the robbery, Culbertson had just run away from home, and his photo was distributed to the police. Documents showed an officer saw the runaway photo and remarked that it resembled one suspect in surveillance video related to the aggravated robbery case.

According to the police, people who knew Culbertson told them it might have been him in the black hoodie. In a police interview with Culbertson, an officer told him no one who knows him well said that it “wasn’t” him, but rather, quickly looked at the photo and identified him.

Investigators had no DNA or fingerprint evidence tying Culbertson to the crime, and the stolen items were recovered and returned to the victim within hours, but a combination of the surveillance video and victim identification during trial were enough for a jury to find Culbertson guilty and to sentence him to eight years in prison.

The other suspect in the surveillance video was not identified or charged during the investigation.

“I blamed everybody, like, I was just mad at the world,” Ryan said. “I think I was more angry because, like, you’re putting my baby in prison. Not in juvenile. But prison.”

The Ohio Innocence Project began looking into Culbertson’s case in 2021 and presented evidence to Stone last year.

Stone was elected as Stark County prosecutor in 2020, after working for three years as a criminal defense attorney. He is the first African American man to be elected a county prosecutor in the state of Ohio. Stephanie Tubbs-Jones is the only other African American prosecutor in the state’s history.

“It’s proven to be beneficial to the administration of justice,” he said. “Being able to have a perspective and a certain experience, life cultural experience, that has never been seen in this position.”

Stone became instrumental for Culbertson’s release after he looked at images from the surveillance video that led to Culbertson’s conviction. Upon seeing them, he said he immediately knew Culbertson was misidentified.

“As an African American male, knowing that Black folks can come in different complexions, and I immediately saw the difference in complexion between the two individuals, and I just knew something was wrong,” he said. “Something was off.”

Stone said Culbertson and the suspect in the video didn’t have the same mouth, nose, chin or forehead, and he immediately knew they had the wrong individual behind bars.

Prosecutors, he said, should push for what’s right, even if it means admitting a mistake had been made.

“If I’ve been given information that says an individual is innocent or that we got it wrong, who cares if our pride is hurt?” he said. “Who cares if it might cause a little bit of embarrassment to the office? It is what it is. We have a responsibility, an ethical responsibility, that we’re just as active trying to get them out of jail or prison like we would when we try to put them there because they’ve committed crimes.”

Brian Howe, with the Ohio Innocence Project and professor of clinical law, said there was no lineup for the victim to identify the suspect in Culbertson’s case.

“There was no request to identify anyone,” he said. “The first time that the victim saw anyone, was asked to pick out anyone in association with this crime, was at the bind over hearing while Aaron was sitting at the defense table. So that’s sort of a textbook, unconstitutionally suggestive identification procedure. It should not have happened here.”

Thanks to the Ohio Innocence Project and the Stark County Prosecutor’s Office, the two men in the surveillance video were identified as Lakim Woody and Alonzo Stinson, Jr., who are currently in prison for unrelated crimes. They admitted to investigators at the prosecutor’s office that they were in the video.

The names of the alternate suspects came to light after the Ohio Innocence Project law students scoured social media and followed leads Culbertson brought up during the time of his arrest, documented in police interviews.

“That is not me,” Culbertson said in one interview. “I know who that is. I know who really that is.”

When pressed for a name, Culbertson said, “That is some boy named, it’s either Kimble or Kimmy or something from McKinley, but that’s all I know about him.”

Woody and Stinson only admitted to being in the surveillance video, not to the aggravated robbery. Stone does not intend to re-try the original case.

“I was more concerned with them being honest to identify themselves to get Aaron out, rather than try to trip them up to admit to them doing the crime and risk them not wanting to talk,” Stone said.

Howe said this case is an example of the flaws in the criminal justice system and the bias that comes with eyewitness cross-racial identification.

“We especially need the kinds of procedures that are going to make sure that we’re not getting it wrong,” he said. “This is the kind of situation where it’s especially important to have, you know, a double-blind lineup procedure. That’s the kind that’s called for by Ohio law, the kind that did not happen in this case.”

Stone acknowledged it is highly unusual for a prosecutor to team up with the Ohio Innocence Project and push for an inmate’s acquittal, but Stone said the state is the one that did this, so it’s also their responsibility to fix it.

“I understand historically that hasn’t happened with prosecutors, but historically, they haven’t had a Kyle Stone as a prosecutor either,” he said.

Culbertson and Stone now have formed a unique bond. Stone even had Culbertson promise to come visit his church after he got out, which he did.

“Yeah, I love Kyle,” Culbertson said. “It’s like having another big brother.”

Culbertson is now focused on building a future for him and his son, Avante, who was only two months old when his dad was found guilty. Culbertson earned his GED in prison and now has a job in an office alongside his sister.

“It feels great to actually work a job and get some income, so I can take care of myself and my son,” he said.

He hopes to earn a college degree in computer engineering and get a CDL, so he can work as a truck driver. Yet, re-integrating back into society hasn’t been easy, and he’ll never recover those four formative years of his life.

His mother died unexpectedly while he was in prison, and it will take time for him to heal from the trauma of wrongful incarceration.

“It was kind of hard,” he said. “Everyday waking up I’d be dreaming about me being with her or me being with my son, and I’d have to wake up to steel doors and a mattress that’s the size of this chair. That’s how I felt every day. I wanted to cry. I want to cry right now, thinking about it.”

But Culbertson is now happy to be home and to be working with his sister. Despite the fresh wounds of a wrongful conviction, he’s looking forward to a fresh start.

“I have experienced every emotion in these past 30 days,” he said. “Happiness, sad, being grateful. My biggest thing is I’m just trying to stay humble.”

According to the Ohio Innocence Project at the University of Cincinnati College of Law, Culbertson is the 38th wrongfully convicted Ohioan the legal clinic has helped release. He is also the youngest client the group has ever worked with.

The Canton Police Department declined to comment on the case.