CINCINNATI — As COVID-19 cases continue to soar nationwide and in Ohio, researchers at the University of Cincinnati say rural areas are getting hit hardest right now in certain parts of the country.

What You Need To Know

- UC researchers say rural regions in parts of the country are getting hit hardest right now

- Local rural areas, like Brown, Clermont, and Adams counties, have remained lower than Ohio metro counties like Hamilton County

- Local rural areas, like Brown, Clermont and Adams counties, have remained lower than Ohio metro counties like Hamilton County

Nationwide, urban areas have seen a higher rate of mortality from COVID-19 than rural areas. However, in high-infection states where the virus is surging, the story is much different, said Dr. Diego Cuadros, an assistant professor of geography at the University of Cincinnati and the director of UC's Health Geography and Disease Modeling Lab.

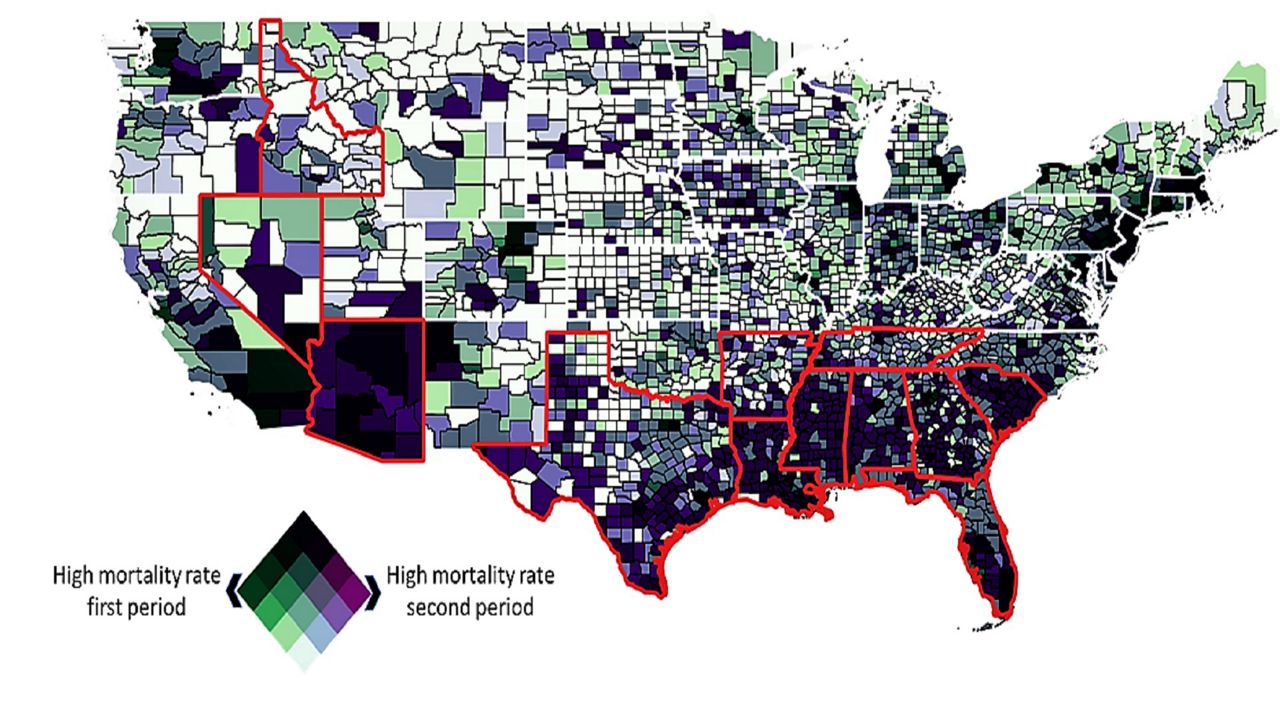

In fact, according to a new study by Cuadros and UC’s Geospatial Health Advising Group, rural areas in some states have higher mortality rates from COVID-19 compared to their metro counterparts, as the epidemic has shifted from the Northeast and mid-Atlantic regions to southern states.

The study was conducted in an effort to also determine what some of the potential causes might be linked to these rates.

"We were interested in trying to identify the factors that were associated with higher mortality risk linked to COVID-19 in the entire country. So, we conducted this analysis, trying to find those risk factors,” said Cuadros, whose advising group is composed of health, geography and statistical modeling experts from the UC College of Pharmacy and the UC College of Arts and Sciences.

Forming in April, the group began looking at nationwide geographic indicators of the virus and mortality rates — providing guidance to health officials in tracking the spread of COVID-19, as well as trends surrounding the virus.

"We found that, for example, the population in poverty (and) African-American and Latino populations were the populations with higher mortality rate. But also, we found other factors, like, for example, pollution. So, areas with higher pollution were also link it to higher mortality rate associated with COVID-19,” Cuadros said.

During the initial portion of their study, he said, they found that Ohio counties with high connectivity, like major highways and airports, experienced higher mortality rates and a much faster diffusion of COVID-19, while counties with lower connectivity, like rural areas, saw a slower spread of the virus overall.

As of Friday, there were 326,615 total cases reported in Ohio, including 7,787 new cases — as well as 63 new deaths, bringing the total death count in Ohio to 5,890, according to the Ohio Department of Health.

In fact, statewide positive test results have increased by 300% in the past month. Currently, there are 3,829 patients hospitalized and 943 of those have been admitted into the ICU.

In the Cincinnati region, rural areas, like Brown, Clermont and Adams counties, have remained lower than Ohio metro counties like Hamilton County, as of Nov. 19, according to each local county health department.

- Brown County: 858 total cases and four deaths

- Clermont County: 4,775 total cases and 45 deaths

- Adams County: 445 total cases and 7 deaths

- Hamilton County: 16,878 total cases and 259 deaths

According to the Ohio Department of Health, all counties in the Cincinnati region, including rural counties, are considered in the “red zone” or level 3, defined as a public emergency with “very high exposure and spread.”

However, the epidemic, Cuadros said, has affected the entire country in different ways.

Ohio’s rural counties have not had the same spike in mortality or cases, like some southern states that the group studied.

While the virus started in metro areas in the north, he said, COVID-19 quickly spread to the south and in the rural-most areas of those states, like in Arizona, Louisiana, Mississippi, Florida and Georgia — and the study concluded a much larger spread of infection in those states’ rural areas.

“We are seeing a very big spread of infection in the rural areas, compared to the open areas, especially in rural areas are the ones who are experiencing a high incidence of infection and also high mortality — we were seeing a reduction of the mortality rate in most part of the country but in these particular (rural) areas, their mortality is not is not declining, it's actually increasing,” Cuadros said.

In the study that they conducted, Cuadros said, his group of multidisciplinary UC researchers, took a microscope to the entire country and found that in those southern states, poverty was a factor in higher mortality rates due to COVID-19. Moreover, age, health and proximity to healthcare services, indicated reasons for the surge of cases in the rural areas, they saw getting hit the hardest.

Age and healthcare accessibility in rural areas, make that population more vulnerable to COVID-19, he said.

“It’s beginning to saturate the healthcare system, which is what we want to avoid,” Cuadros said. “People really want to go back to normal and it’s not happening anytime soon. It’s hard to convince people that they need to take precautions.”

This requires a new approach to battle the ongoing pandemic, he advised.

Based on their study’s findings, UC’s Geospatial Health Advising Group made the following nationwide recommendations, specifically in rural areas of the country:

- Urging government health agencies to recognize the disproportionate impact COVID-19 is having on rural areas when drafting county-level policies to address the pandemic.

- Making residents in rural areas aware of the risks they face so they can take personal measures to protect themselves.

- Improving health care resources in rural areas through health partnerships, particularly for critical access hospitals.

Regardless of geography, Cuadros said, prevention is going to be key moving forward, and that means, wearing a mask, limiting contact with others, and avoiding gathering in groups, including over the holidays, or what he calls, “super-spread events.”

“This connectivity is the perfect condition for experiencing a surge of the infection. I know that Thanksgiving is a very important event,” he said. “It will be very hard to tell people to stay home, no family gatherings, (but) that will be the best strategy.”

"The best suggestion is try to avoid infections, which means try to reduce the probability of transmission. Unfortunately, we don't have a vaccine yet, which is the most effective way of controlling these kinds of infections. So, the only thing that we have is non-pharmaceutical interventions,” he said, adding examples like, staying home, lockdowns, curfews, social distancing and wearing a mask, to reduce the spread of COVID-19.

In fact, Gov. Mike DeWine recently announced a statewide order that will be in effect for the next 21 days.

On Friday, Ohio Department of Health director, Stephanie McCloud, signed a health order that encourages residents to stay home, especially over Thanksgiving.

“As COVID-19 continues to spread in Ohio, we need a stronger response to minimize the impact on Ohio’s healthcare and hospital capacity and ensure healthcare is available to those that need it,” DeWine said. “With this order we are discouraging get-togethers and gatherings to minimize the spread of the virus, while minimizing the economic impact of a complete shutdown.”

Specifications in this order include:

- Individuals within the state must stay at a place of residence during the hours of 10 p.m. and 5 a.m., except for obtaining necessary food, medical care, or social services or providing care for others.

- This order doesn’t apply to those that are homeless. Individuals, whose residences are unsafe or become unsafe, such as victims of domestic violence, are encouraged to leave their homes and stay at a safe, alternative location.

- The order does not apply to religious observances and First Amendment protected speech including activity by the media.

- The order permits travel into or out of the state and permits travel required by law enforcement or court order, including to transport children according to a custody agreement, or to obtain fuel.

Individuals are permitted to leave a place of residence during the hours of 10 p.m. and 5 a.m., for the following essential activities:

- Engaging in activities essential to their health and safety or the health and safety of those in their households or people who are unable to or should not leave their homes, including pets. Activities can include but are not limited to seeking emergency services, obtaining medical supplies or medication, or visiting a health care professional including hospitals, emergency departments, urgent care clinics, and pharmacies.

- To obtain necessary services or supplies for themselves and their family or members of their household who are unable or should not leave their home, to deliver those services or supplies to others. Examples of those include but are not limited to, obtaining groceries and food. Food and beverages may be obtained only for consumption off-premises, through such means as delivery, drive-through, and curbside pickup and carryout.

- To obtain necessary social services.

- To go to work, including volunteer work.

- To take care of or transport a family member, friend, or pet in their household or another household.

- To perform or obtain government services.

With a COVID-19 vaccine on the horizon, Cuadros and his team at UC are in the process of conducting a new study regarding the vaccine and its delivery.

“We have to also be smart, in terms of how we're going to deliver vaccination,” he said. “Trying to identify those vulnerable areas that vaccination could be more efficient is something that could be a good strategy, trying to control the epidemic and also try to avoid potential deaths in the specific parts that the most vulnerable population is residing."

For more information about how you can prevent the spread of COVID-19 and a complete list of testing sites, visit Hamilton County Public Health Department’s website.

For more information about how to have a safe holiday season, visit the holiday celebration guidance page.