This year got off to a fast start for severe weather, especially for tornadoes. The number of known tornadoes in recent years is higher than it was a few decades ago, but there’s more than one reason for that.

First, some philosophy: “If a tree falls in the woods and nobody’s there to hear it, does it make a sound?”

That also applies to tornadoes. If nobody knows about it, it can’t get counted. And if one happens, it’s rated based on the damage it causes, which doesn’t necessarily match its true strength. A mile-wide tornado that doesn’t hit anything doesn’t get an EF-5 rating.

Back in the 1990s, the number of reported tornadoes jumped up… but only for the low-end tornadoes. So let's look at the multiple reasons why that's the case.

The connection between climate change and tornadoes is complicated. According to Yale Climate Connections, we can make a long story short: Researchers haven’t found a clear trend in the number of tornadoes each year.

On the other hand, they have seen more “clumping” of tornadoes since the 1970s. That is, fewer days have a tornado, but more days have multiple tornadoes. That also means there’s been more tornado outbreaks.

If climate change isn’t causing more tornadoes (at least, not yet), we have to consider other factors.

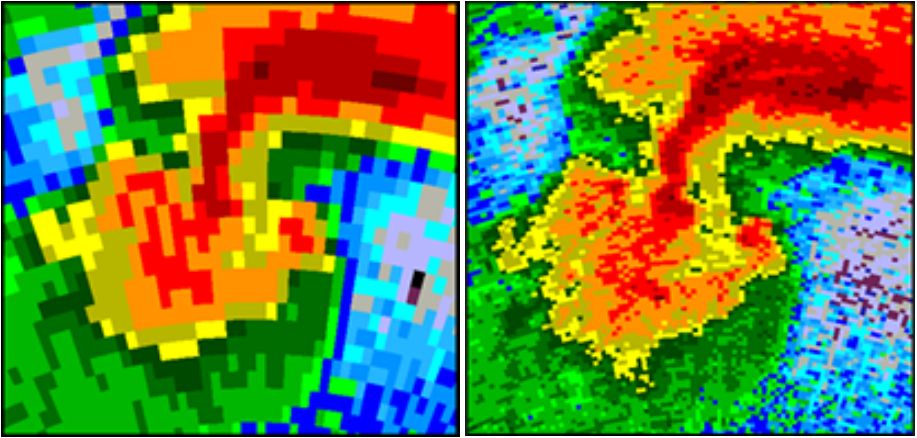

Doppler radar lets us peer into the heart of a storm, seeing how the winds are moving within it.

The NWS installed the current network of National Weather Service Doppler radars (also known as NEXRAD) in the 1990s, right around the time when the number of observed tornadoes went up. Matching rotation paths to damage reports made finding the weaker tornadoes easier.

But that was just the start.

In the late 2000s, NEXRADs got an upgrade to “super resolution.” Remember how much crisper TV looked after everything became high-definition? It was like that, and meteorologists could now see even small bits of rotation. That’s especially helpful for spin-up tornadoes embedded in lines of storms.

In the 2010s, NEXRADs got another upgrade. “Dual polarization” was like going from black-and-white to color TV: things were visible like never before, such as tornado debris.

Picking out spin-ups within a squall line–and knowing to look for tornado damage amongst straight-line wind damage–also meant finding more low-end tornadoes.

We once thought these types of systems made up about 20% of tornadoes, but researchers now think it might be closer to 30%, partly because we know about and find them better now.

And NEXRADs now scan the lowest part of storms more often, checking that spot every 90 to 120 seconds. “When it is a brief tornado and you're scanning every five minutes, you're probably going to miss a lot of these tornados on your radar,” says Tim Halbach, the warning coordination meteorologist at NWS Milwaukee.

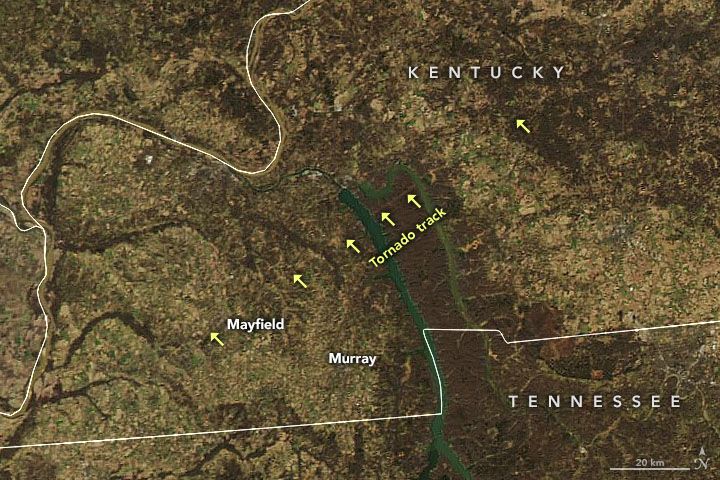

Meteorologists are even using high-resolution satellite images to help them find tornado paths.

Halbach says it helped them in Oct. 2022: “We were actually able to pick out two tracks because the corn hadn't been harvested yet in a couple fields. We had a TDS (tornado debris signature) and we had a ground survey go out and try to look for damage in that area before looking at the satellite data and couldn’t find anything. And then we went back on the data and we swiped back and forth and were like, ‘Oh, here's the path!’”

There’s also the so-called “‘Twister’ effect.” The blockbuster movie about tornado researchers helped spawn the storm chasing boom. Tornadoes in very rural areas that may have gone unnoticed in the past now have droves of people spotting them.

Cities and suburbs growing outward create an “expanding bullseye,” which puts more people at risk of tornadoes… but also seeing them. Even these people who aren’t storm chasing can take photos or video more easily thanks to smartphones.

Our team of meteorologists dives deep into the science of weather and breaks down timely weather data and information. To view more weather and climate stories, check out our weather blogs section.