Plants in gardens and fields survive and thrive based on the weather where they grow. But as the coldest temperatures of winter gradually warm, those plants’ favored regions also change.

If you have outdoor plants that stay in the ground through the winter (perennials), you care about what “plant hardiness zone” you live in. But it’s not just gardeners and growers’ plants that matter. These zones also affect wild or invasive plant species, along with insects.

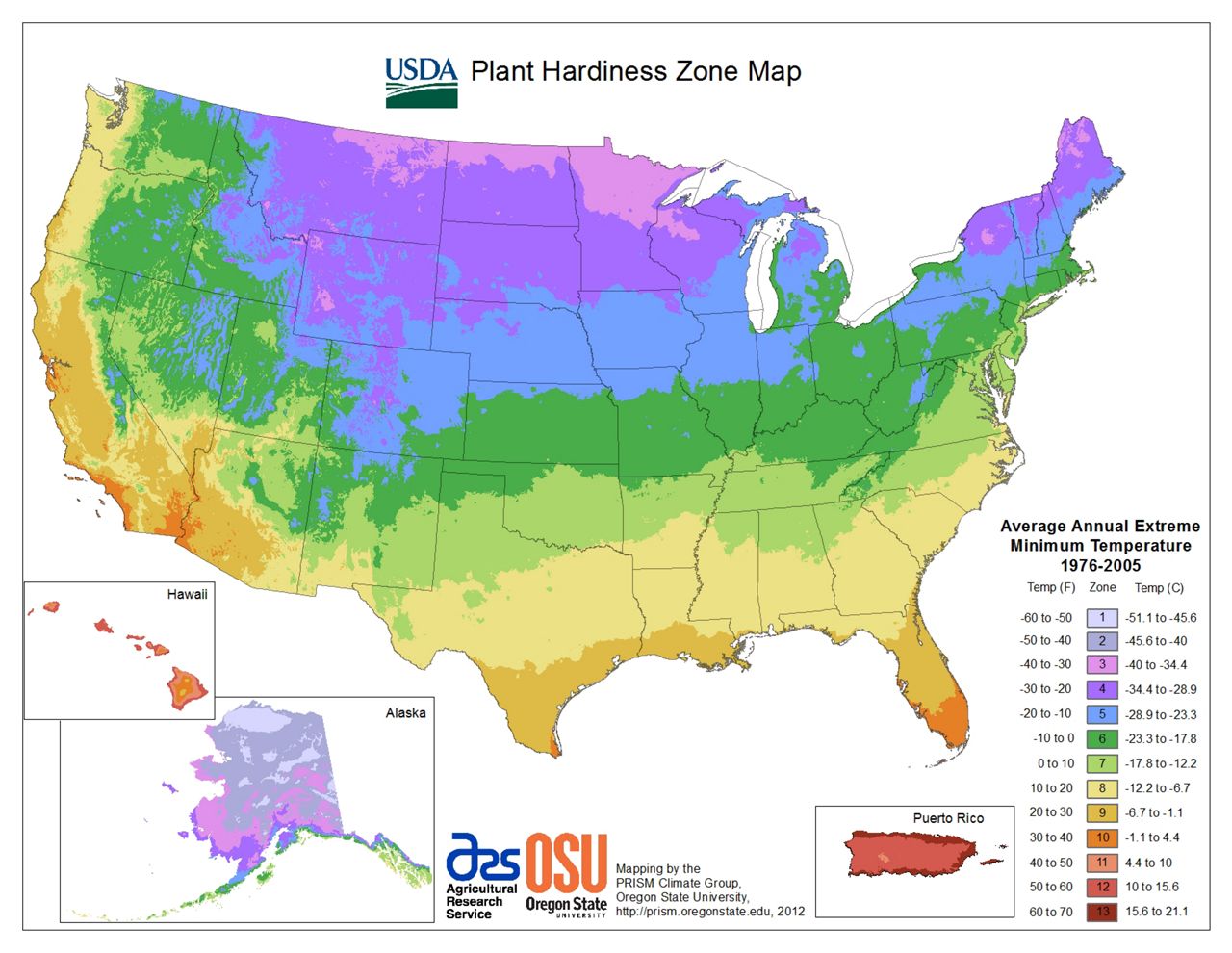

They’re regions that are based on the average coldest temperature of the winter.

Each zone spans a 10-degree range (like 10 to 20 degrees), although the zones are often subdivided into five-degree chunks. For example, Zone 1a, the coldest, has an average minimum winter temperature of -60 to -55 degrees, but Zone 13b, the warmest, is typically no colder than 65 to 70 degrees.

Both the USDA and NOAA have plant hardiness maps, but they’re quite similar. NOAA’s last official map update was in 2010. Here’s the USDA’s most recent map, which was updated in 2012.

NOAA’s climate “normals” are 30-year averages updated every decade, and the most recent one runs from 1991 to 2020. According to Climate Central, planting zones have generally shifted northward in each of the past three climate normal updates.

Here’s how they changed from 1971 to 2000, 1981 to 2010 and 1991 to 2020.

Climate Central found that the coldest average temperature since 1951 warmed in 95% of the 242 U.S. locations they studied. Half of them, at some point, moved to a higher plant hardiness zone.

Going from one zone to another doesn’t make everything suddenly change. The process is gradual, but the range of some plants and crops has expanded. Sometimes that’s fine, and sometimes that’s bad.

For example, kudzu is an invasive vine that is expected to expand farther north. Insects and other pests that prefer certain plants will also move with them.

In a relatively lower carbon emissions scenario, the USDA predicts most of the change in plant hardiness zones from 2070 to 2099 will be in the Great Lakes and Midwest. High emissions, however, would make a much broader and larger change in plant hardiness, with some northern locations jumping up a couple of zones.

Our team of meteorologists dives deep into the science of weather and breaks down timely weather data and information. To view more weather and climate stories, check out our weather blogs section.