America is remembering former President Jimmy Carter ahead of Thursday’s funeral service at the National Cathedral in Washington and his burial back home in Georgia.

Presidential funerals have a rich history, with the public farewells often revealing a bit about the individuals who held the office and their time leading the country.

Carter is no exception.

The Early Years

As with most presidential traditions, George Washington is a good place to start.

The United States’ first commander in chief requested a private funeral, without public eulogies or parades. But that wish was denied.

“Hundreds of mourners flocked to Mount Vernon to pay their respects,” said Matthew Costello, with the White House Historical Association. “Mock funerals are held throughout the entire country, celebrating George Washington as a national figure.”

Throughout the 19th century, presidential funerals would vary in size from small local gatherings to large outdoor tributes.

The funeral procession in New York City for Ulysses S. Grant in 1885 drew an estimated 1.5 million people, the largest demonstration in the country to that point.

Grant, who as a general led the Union to victory in the Civil War, was buried in Riverside Park on Manhattan’s Upper West Side in a temporary tomb until a mausoleum was constructed in his honor and completed in 1897. It remains the largest mausoleum in North America to this day.

Louis Picone, the author of the book "The President is Dead!" said Grant’s death was “really seen as the right moment, the right man almost to celebrate reunification and reconciliation.”

“Even at the funeral, there was some former Confederate soldiers that had marched in the funeral procession,” Picone said.

Lincoln establishes the standard

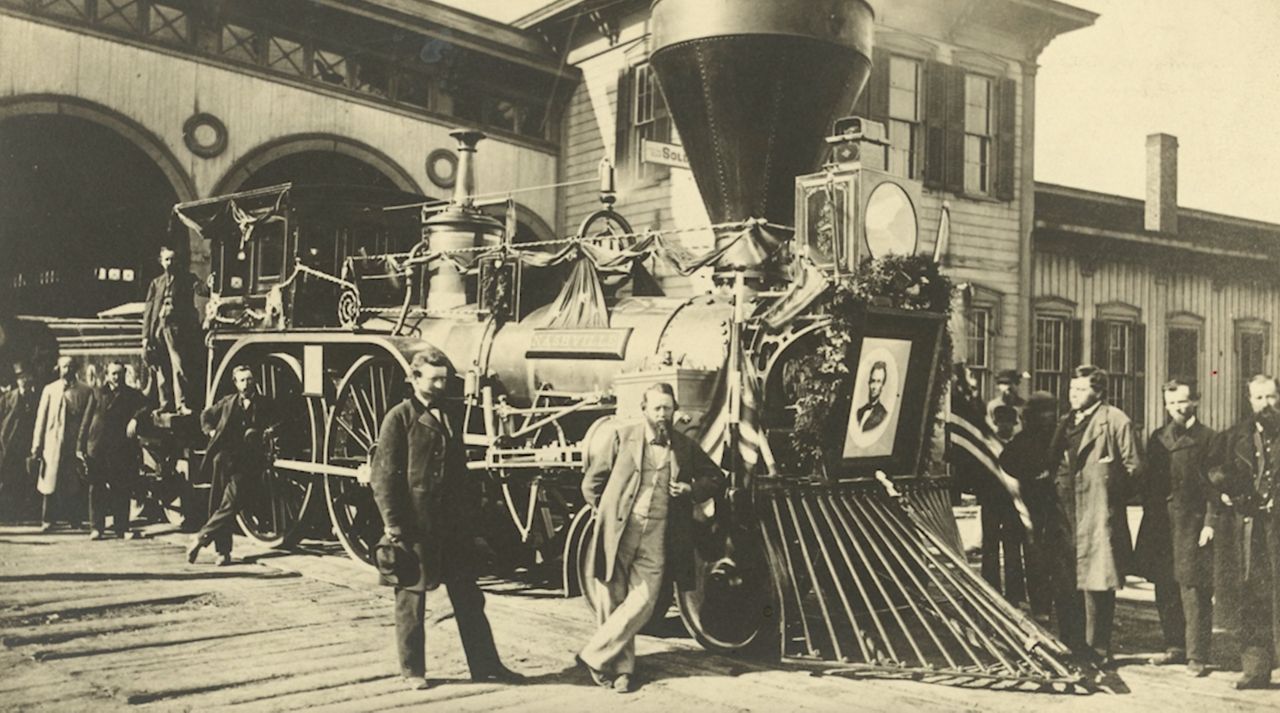

The death of Abraham Lincoln after being shot at Ford's Theater in Washington, D.C. helped establish the standard for presidential memorials.

Lincoln was the first commander in chief to lie in state in the U.S. Capitol rotunda, a now common practice.

Thanks to the growing ubiquity of the railroad, many Americans participated in the grieving process firsthand. Lincoln’s funeral train made a 1,700 mile journey, with several stops including in New York, Philadelphia, and Chicago.

“Approximately 1.5 million people saw Lincoln's remains. Approximately eight million people would have either seen the funeral train or seen the procession,” Picone said.

Nearly a century later, when another assassination rocked the nation, John F. Kennedy’s wife Jackie looked to Lincoln’s funeral as a model for how the country would say goodbye.

Kennedy’s funeral was the first broadcast on television, allowing even more Americans to participate.

Since then, these funerals are now very public affairs and the rituals are often familiar.

Presidents begin planning their funerals while still in office, giving them more of a direct say in what their final sendoffs look like. What traditions they choose to follow — or not — reveal a bit about who they are.

Harry Truman, for example, opted for a smaller service back home in Missouri.

“Truman did not see himself as sort of president-for-life,” Costello said. “I think he rejected the pomp and the pageantry often associated with the presidency. And Independence was the place that he loved.”