CLEVELAND — Gulnar Feerasta said her self-discovery journey began when she came out for the first time, during an interview at the LGBT Community Center of Greater Cleveland in 2018.

“I just remember saying, you know, as somebody who is an immigrant who is a person of color who's Muslim and is also queer … centering marginalized identities, it's just so important to me,” said Feerasta, who uses she/they pronouns.

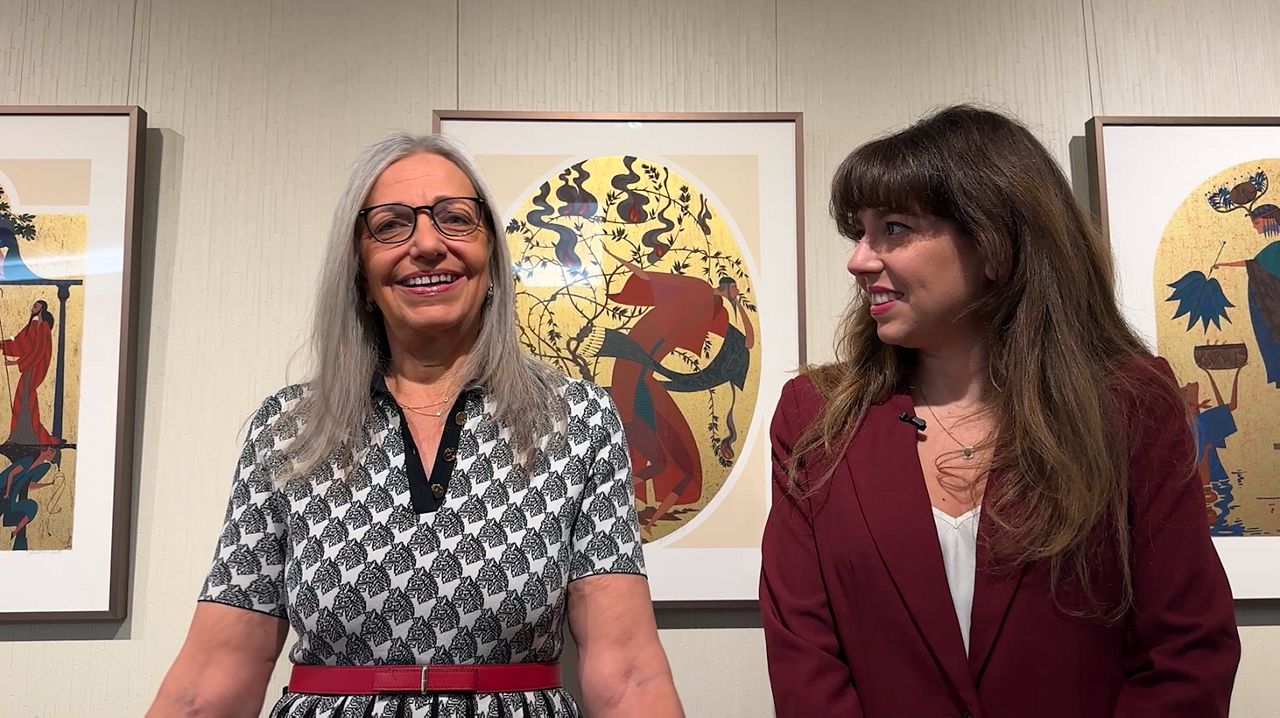

Feerasta is now the managing director at the center and is spearheading the group’s collaboration with the Kent State University School of Public Health for the Greater Cleveland LGBTQ+ Community Needs Assessment project.

“When you come in, you can come in as your full, authentic self, whereas in other spaces there might be parts of you that you have to leave at the door,” Feerasta said.

Over the last two years, researchers looked into the needs and challenges faced by the LGBTQ+ individuals in Cuyahoga, Lake, Lorain and Geuaga Counties. After conducting and analyzing thousands of community surveys, intersectionality listening sessions, stakeholder interviews and tabling at pride events, the LGBTQ+ assessment team published the project’s results last month.

Researchers said these findings are part of a six-year project, and they’re focusing on Greater Akron area next.

Andrew Snyder, adjunct faculty at the Kent State University School of Public Health, said the group connected with more than 120 community organizations, asking a series of questions looking at various quality of life factors.

“It had over 130 questions on it. And these questions were very holistic in terms of health,” Snyder said. “So we didn't just ask about health in its traditional sense, physical, mental or spiritual emotional health, but we also leaned into things like recreation and leisure and religion.”

His colleague, graduate assistant Jehlani White, said these findings will help them fill a critical information gap.

“Being able to have concrete evidence that can help fund initiatives, help support them, whether it's in housing, basic needs, transportation, anything like that,” White said.

The results will also help them address racial disparities within the community, he said.

“As someone that is Black and trans, I really hope that the racial equity report and the full report reaches everyone and that it inspires change,” White said.

With the data, Feerasta said they’re breaking away from a cycle.

“When you don't exist in the data, then you don't exist in the funding, [and] you don't exist in the policies,” Feerasta said. “And that's sort of what we've experienced over and over again.”

Feerasta said they plan to keep the ball rolling.

“It took us 50 years to get to this point in some ways, right? To get to a point where we can have the resources,” they said. “I just don't want it to be another 50 years before we then have the resources to actually do a community health improvement plan, a CHIP.”