CINCINNATI — A new study released this week showcases how doctors and scientists across the nation and in Ohio are working to reduce opioid-related deaths. While the findings may not have been all they hoped for, the study is bringing evidence-based practices across the state to continue to make an impact.

What You Need To Know

- The results of the Community HEALing study were just released at a conference in Montreal

- The study, led by two researchers from UC and OSU, aimed to significantly decrease opioid-related overdose deaths

- While the sudy didn't see a significant change in opioid-related deaths, it did implement more than 250 evidence-based practices in ERs and jails to help those struggling with opioid abuse

- The study was implemented in counties across five states

Dr. Caroline Freiermuth is an emergency room doctor and has seen it all.

“We know that many people come into the emergency department for things like unexplained fever, and really they’re in withdraw, but they don’t want to tell us they’re in withdraw," Dr. Freiermuth said. "And so we need a way to easily screen people.”

In the last few years, she and her team have been working to help those with opioid-related illnesses. And thanks to a recent study, spearheaded by doctors at both UC and Ohio State, they’ve been able to implement changes, like screening questions on opioid use.

“The HEALing community study came with funds and came with some technical assistance, and we were able to utilize that to help move things forward," she said. "So they really were focused on screening and then they were focused on how do we treat people and how do we really initiate medications for opioid use disorder.”

The HEALing Community study was a culmination of several years of hard work in which scientists helped implement more than 250 evidence-based practices in places like ERs and jails to change clinical care in hopes of drastically reducing opioid-related deaths.

“It was an enormous success," said Dr. John Winhusen, the director of UC's Center for Addiction Research and co-principal organizer of the study. "In Ohio, we had 18 counties participate, and in those 18 counties, we implemented over 250 evidence based practices. Most of those were focused on increasing naloxone distribution.”

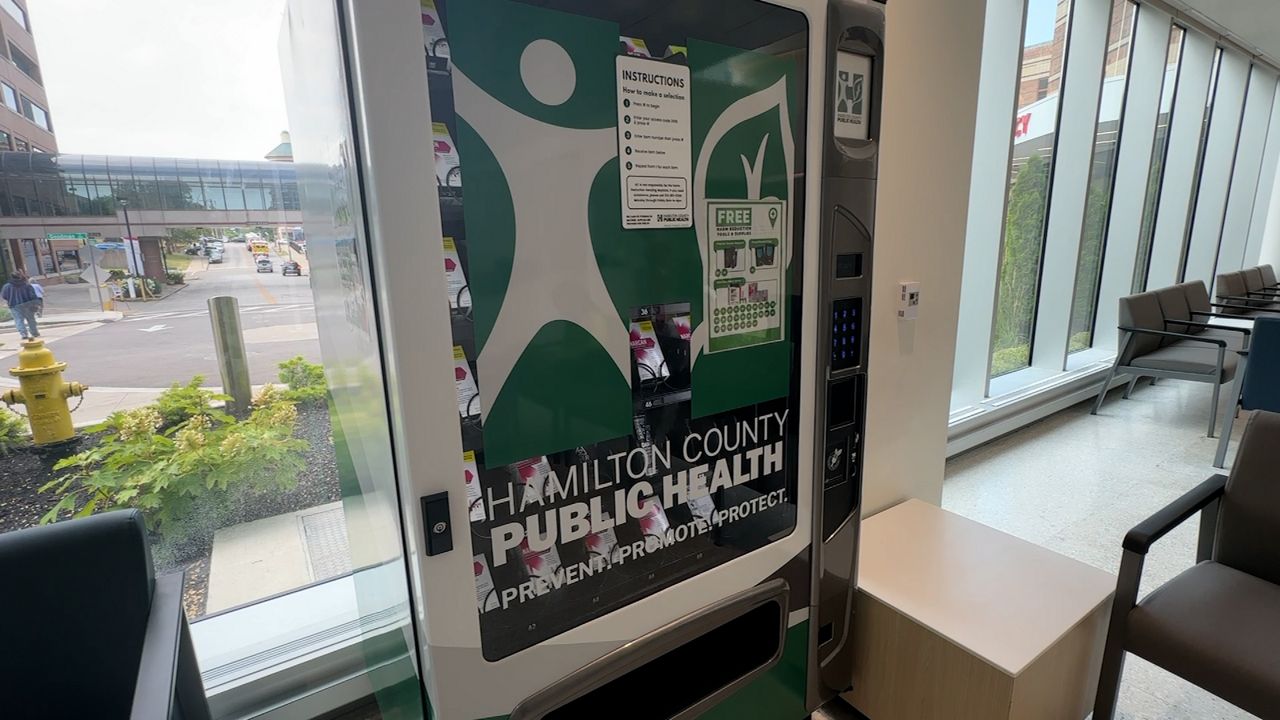

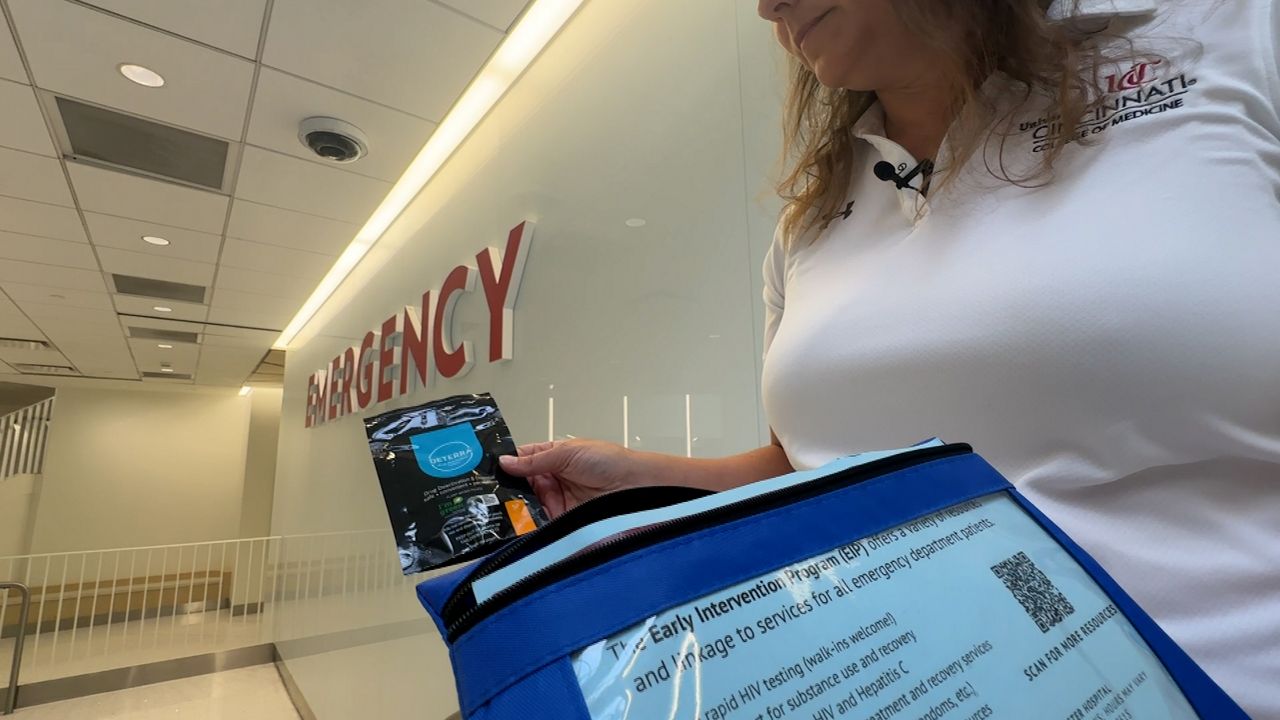

Winhusen was pleased to see practices implemented right in his own hospital. Beyond screening, narcan is made available through doctors and nurses and even a vending machine in the ER. Safety kits are also handed out to anyone that presents a risk of an opioid overdose.

While researchers found no statistically significant reduction in opioid overdose deaths during the evaluation period, when the research was presented at the college on problems of drug dependency conference, there was hope things could turn in the right direction.

“They were just just so impressed with everything that we accomplished," Winhusen said. "Despite the fact of not seeing a statistically significant difference on the primary outcome, usually that, you know, people are hyper focused on that, this audience just saw the bigger picture and was just like, 'wow, everything you've done is amazing.'”

And Ohio is trending in the right direction. According to the Ohio Department of Health, there was a 5% decrease in the number of unintentional drug overdose deaths from 2021 to 2022, while the same number increased by 1% across the nation. And in Ohio’s largest counties in those same years, Cuyahoga County saw a decrease of 4%, Franklin a decrease of 5% and Hamilton by 16%.

“There are probably a lot of factors that go into that," Freiermuth said. "But we really like to think that a big part of that is what things that we're doing here in the emergency department.”

While the study is in its final year, the hope is that these evidence-based practices continue and expand across more counties across the state.