LAKE ERIE — Out near Put-in-Bay, Chris Winslow leads scientists from all over the Midwest in freshwater biology research and science education.

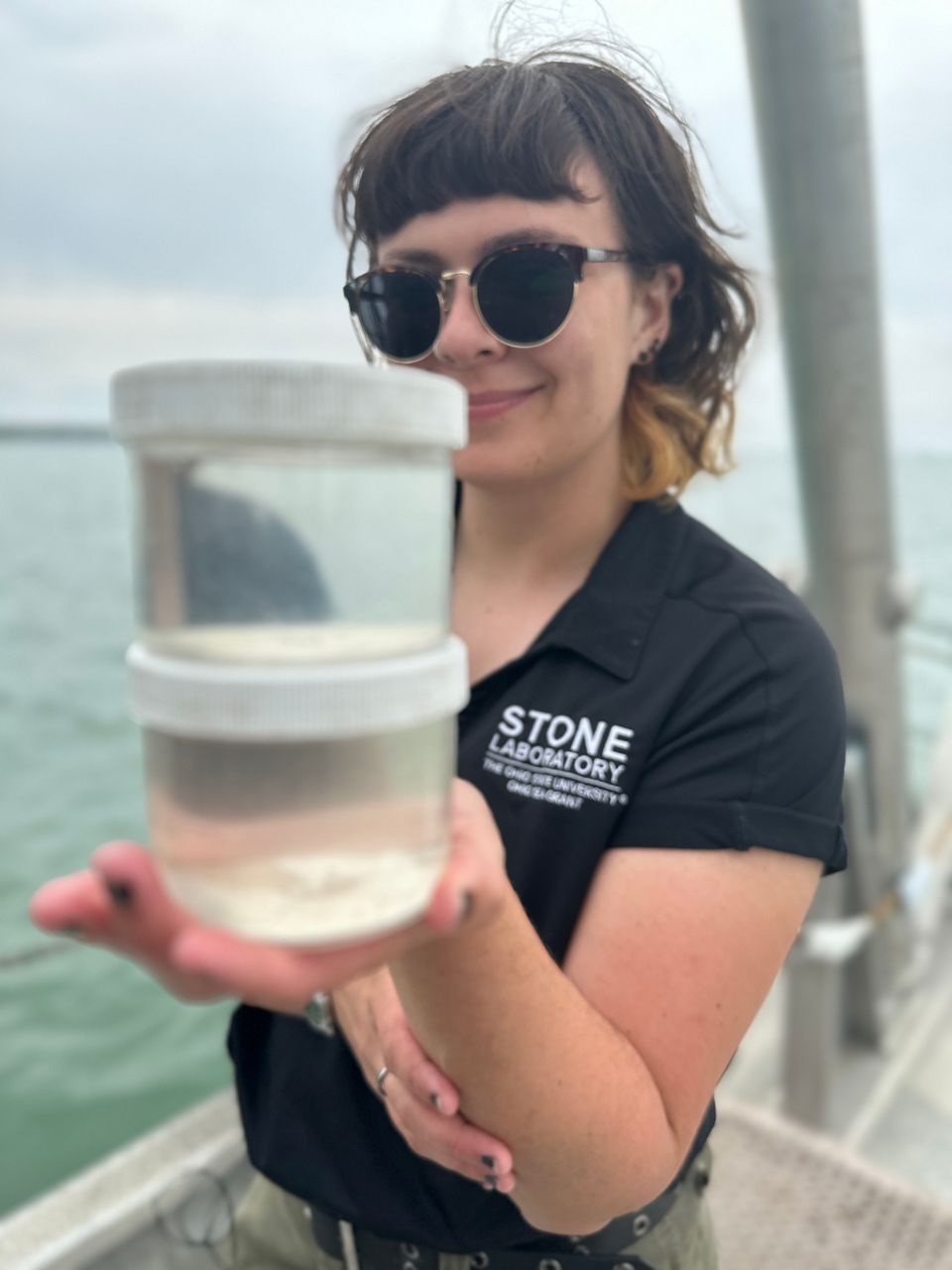

He’s the director of the Ohio Sea Grant and Ohio State University Stone Laboratory and has been studying Lake Erie for more than 20 years. He’s often out on the lake in one of their research vessels.

“The vessel’s outfitted to do pretty much anything,” Winslow said. “We can pull nets for fish, we can do sampling for plankton, so the critters living in the water column, we can sample the bottom of the lake.”

With the environment warming because of climate change, each winter that comes and goes, he said he’s noticing some drastic fluctuations. This year, Lake Erie, the smallest of the five Great Lakes, had little to no ice coverage.

“We've had pretty ice-free years before, this is not an anomaly,” Winslow said. “Some years, you might see a lot of ice and the next year, you may see none. And that's not what we see on the historic record. If you see a high ice year, you're probably going to see three or four years in a row with high ice. And then if that ice drops off, you might see three or four years of low ice. What we're seeing with climate change, and how it shows up in the Great Lakes, is just variability from year to year to year.”

The Great Lakes are 20% of the globe's freshwater in one location.

“Lake Erie, because it's shallower and warmer than the other great lakes, it freezes over more frequently than the other four. So to have an absolute absence of ice is a big deal,” Winslow said.

He and his team are already noticing effects on things like erosion and water levels and said as spring approaches, they could see effects on fish hatches and algal blooms.

“If you have ice on the lake, you don't have waves,” Winslow said. “When that ice isn't there, you have wave action all year round. The other thing is, we know that organisms live underneath that ice. It can be algae and other critters under that ice. And so when they're there, they're playing around with the water chemistry by using nutrients. So when that ice isn't there, those organisms aren't there. And that affects the chemistry of the lake.”

Winslow said ice is just one piece to the puzzle. He said studying Lake Erie is complicated because it affects so many aspects or components of the ecosystem.

“We know that underneath ice, you have algae that grow," he said. "And so those algae are pulling nutrients out of the water, if you don't have ice, then you don't have those populations growing underneath the ice and therefore it changes how the nutrients are used in that year, and so all of these things feed in on each other. The nutrients feed into the algae and the algae feed into the tiny bugs and up the food chain. And so anything that you change in that has ripple effects.”

He and the other researchers who work on the lake are adding data to a collection project that’s been running since about the 1960s. The research is shared with organizations like NOAA, the National Science Foundation, state and federal agencies, as well as universities.

“You can you can see how temperature and dissolved oxygen at the very least, water chemistry metrics are fluctuating you know, from year to year,” said Calen Campbell, a biological field station assistant at The Ohio Sea Grant and Ohio State University Stone Laboratory. “We can compare this to maybe a day in the 1970s, or 50 years from now they could compare it to now. So it’s a really valuable dataset.”

Winslow said he’s really noticed the major fluctuations in the past decade. Because it’s relatively new, he said they’re still working out the science on the effects of when the lake has a lot of ice coverage during winter versus when it has little to none. He said they’ll have to continue studying the lake for years to come.

“It’s one of those things when you talk about fish, ice might be good for some of those fish species, and no ice might be better for others,” Winslow said. “So it is really just an ever changing dynamic system.”

He plans to continue tracking the effects that climate change and ice coverage have on the lake. He said, it’s his way of doing his part in helping keep the Great Lakes great.

“We always say as scientists, you can’t manage what you don’t measure and so that’s why the research we do on a daily basis informs decisions to help protect and improve Lake Erie,” Winslow said. “There’s no difference between a healthy environment and a healthy economy. When this body of water in our backyard is doing well, the fish are doing well, the water is of good quality, people want to live here. It’s an amazing and beautiful, beautiful place. It’s an amazing resource, and we just shouldn’t be taking it for granted.”

Winslow said addressing greenhouse gas emissions and reducing our reliance on fossil fuels can help protect the lake as well as reconstructing wetlands to water can soak into the ground easier and prevent runoff from going into the lake.

For more information about the Ohio Sea Grant and Ohio State University Stone Laboratory and the work researchers are doing, click here.

Correction: A previous version of this story incorrectly attributed a quote. This has been corrected. (June 12, 2023)